Democrats requested Pennsylvania mail ballots at higher rates than Republicans in every county

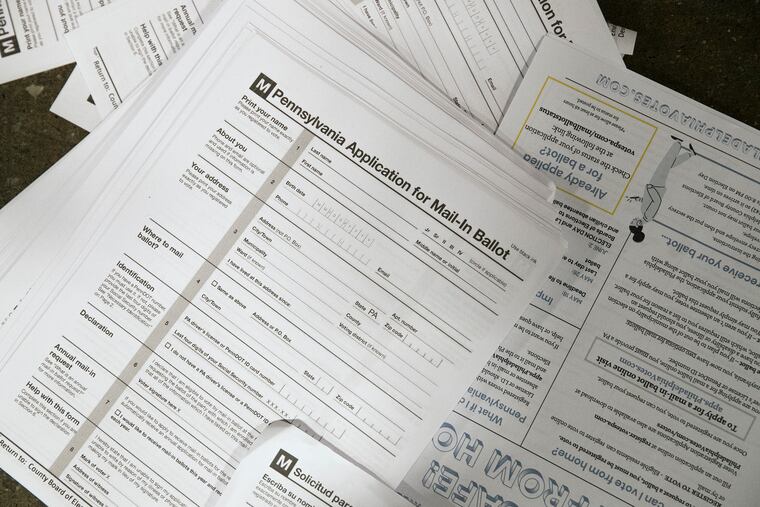

Nearly 18 times as many Pennsylvanians have requested mail ballots this year as in the 2016 primary, fueled by both a change in election law that allows anyone to vote by mail and a pandemic that makes it riskier to vote in person.

Elections officials expected a flood of requests for mail ballots this year.

What they got requires Noah to build an ark.

Nearly 18 times as many Pennsylvanians have requested mail ballots this year as in the 2016 primary, fueled by both a change in election law that allows anyone to vote by mail and a pandemic that makes it riskier to vote in person.

Pennsylvania Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar said Thursday that she expects a majority of votes to be cast by mail in Tuesday’s election, a massive jump from the 5% absentee rate of past elections. About 1.9 million Pennsylvanians have requested mail ballots this year, compared with 107,000 in 2016.

And those ballots are being sent mostly to Democrats and older voters, a review of data on state mail-ballot requests show.

Here’s what we found when we looked at where those requests are coming from and what, if anything, it can tell us about voter behavior.

Democrats are clearly fueling the surge in mail ballots, requesting nearly 2.5 times as many ballots as Republicans.

It’s unclear why, but there are a few likely factors, including a partisan divide over vote-by-mail, a noncompetitive Republican presidential primary, and a growing partisan split over how seriously to treat the pandemic.

President Donald Trump has denounced voting by mail, falsely, as an invitation to rampant fraud. (There is no evidence of widespread voter fraud, by mail or in person, and Trump and several of his close advisers themselves vote by mail. Both parties are encouraging supporters to vote by mail.)

It’s also possible there’s simply less interest from Republicans in the primary election.

Both presidential primaries are all but officially decided — but on the Democratic side, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders remains on the ballot, which could be turning out more Democratic voters.

“If you’re on the incumbent side, you may not have voters who understand or know there are other races,” said Tammy Patrick, senior adviser for elections at Democracy Fund, a bipartisan foundation dedicated to voting rights. “So I think that in many cases because one party didn’t have a presidential primary, that can also contribute.”

The pandemic could also be having an effect on the partisan split over absentee requests.

Despite public polling that shows a majority of Americans want to abide by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention precautions, the GOP narrative, led by Trump, has been to reopen faster and downplay the severity of the virus, whereas Democrats have called for a more cautious approach.

Even wearing a mask has become political to some.

“Some of the rhetoric we’re hearing is that there’s one side that believes this is a hoax and one side that believes it’s not,” Patrick said. "That can tie into how those cohorts choose to participate in the election.”

Before 2020, Patrick said, there was no partisan split over voting by mail, which is common in red and blue states.

Patrick wonders whether Republican requests slowed as Democrat requests sped up — as was the case in Pennsylvania — due in part to some of the political debate around absentee ballots.

“We have a narrative that’s come out that we should be questioning the legitimacy of vote by mail and casting doubt on it as an option for voters," she said.

Although Democrats have a voter registration advantage statewide, they requested mail ballots at disproportionately high rates in every single county across the state.

Take, for example, heavily Republican Potter County, where Democrats make up just 1 out of 5 registered voters — and requested 1 out of 3 mail ballots.

It’s unclear whether turnout in the primary will predict turnout in November.

“Are Democrats perhaps setting themselves up for some wishful thinking?” asked Edward Foley, director of Election Law at Moritz College of Law at Ohio State University. “Maybe. Social science data says vote by mail isn’t intrinsically advantaging one party over another.”

Among Foley’s biggest concerns is that the public — and the media — practice patience as results start to come in, particularly in November, given the high number of ballots that won’t be counted the night of.

The median age of voters requesting mail ballots is 61.2, meaning half of the Pennsylvania voters who requested one are older than that.

Mail ballot requests have come disproportionately from older voters, with voters over the age of 55 making up 61% of requests and 43% of registered voters.

“We’re seeing in states like Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan, the consumers are saying they want to vote by mail,” Foley said. “It’s not just the pure convenience of it but is definitely being affected by the health pandemic ... and we know older voters are more at risk.”

Patrick noted that, in states where registered voters are automatically mailed ballots (Pennsylvania is not one), seniors far outnumber voters younger than 25 in registration.

“For younger voters, not registered, if they’re not getting a ballot in the mail they may not know that’s an option," she said. "We saw this in some data from 2018 where we had more voters going to the polls on Tuesday in some states where they traditionally had a higher percentage of vote-by-mail than in person. We think some of that is first-time voters don’t know they have options.”

How many people who request ballots actually vote and how that behavior translates to November is something political scientists and both parties will be watching carefully. These are big changes happening very quickly, Patrick said.

“Instead of going along an evolutionary path that usually takes a state about a decade, we are jumping way ahead,” Patrick said. “So, in this moment we can assume nothing.”