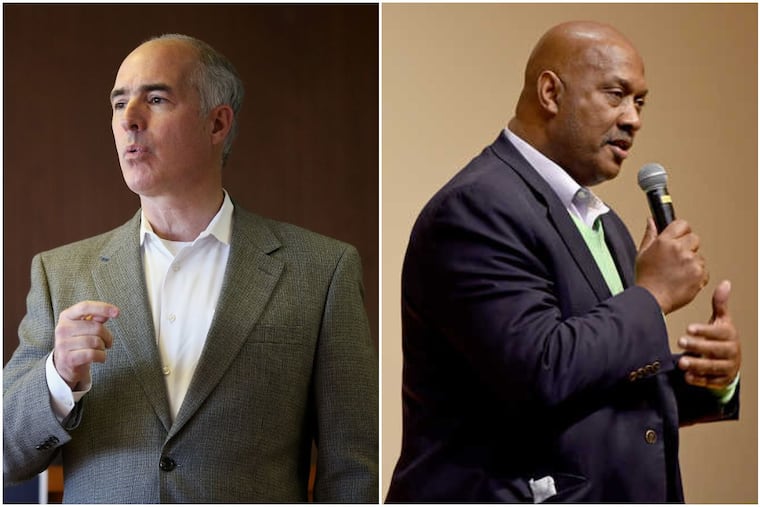

Gun violence victims still feel forgotten. Sen. Bob Casey and Rep. Dwight Evans hope to change that.

Following a 2018 Inquirer report on the struggles faced by gun violence victims in the U.S., two lawmakers are cosponsoring a Resources for Victims of Gun Violence Act.

Four months into 2019, nearly 400 people have been shot in Philadelphia.

Most have survived, thanks in no small part to the frenzied work of the city’s trauma surgeons. But just because someone manages to cheat death in an operating room doesn’t mean he or she won’t face months or years of struggling to recover, to adapt to a new life full of physical and psychological disabilities that create significant needs.

For many of those victims and their loved ones, day-to-day survival depends on being able to navigate a confusing maze of state, federal, and local government bureaucracy as they try to stitch together enough aid for basic necessities, like functional wheelchairs and handicapped-accessible housing.

This American problem affects more than 100,000 people every year, in rural areas and cities alike. But it’s also an issue that hasn’t been meaningfully studied. On Tuesday, U.S. Sen. Bob Casey and U.S. Rep. Dwight Evans cosponsored the Resources for Victims of Gun Violence Act, which promises to establish a federal advisory council to support victims of gun violence, and identify gaps in the myriad support systems.

The council, which will be made up of gun violence survivors and an assortment of federal agencies, will be tasked with submitting a report to Congress within 180 days of the bill’s passage that documents which programs are effective and whether new services are needed.

Casey’s and Evans’ bill comes in response to a 2018 Inquirer investigation about the lifelong burdens shouldered by survivors and their families.

“Your work really spotlighted a huge problem,” Casey said. “It’s not one that gets a lot of attention.”

Jalil Frazier, one of the victims highlighted in that story, was shot and paralyzed while shielding three young children during a barbershop robbery in January 2018.

Last week, Frazier was honored for his heroic act during a fund-raiser hosted by Northwest Victims Services at the Morris Arboretum. Frazier shyly uttered a few short words of thanks from his wheelchair when he was presented with an award.

Later, as attendees chatted and listened to music, Frazier quietly sought information for a physical therapy program he’s seeking.

When he was first shot, he struggled with depression that made it difficult for him to get out of bed. But now, more than a year since the shooting, he feels stronger and more determined to get his life back. But he still has trouble finding the right programs.

“I’m ready to do more,” he said as several people started to brainstorm about where he could find the therapy he wanted.

Frazier has found the most reliable source of information about available aid in the unlikeliest of places: Instagram. There, he connects with other paralyzed gunshot victims, who are also struggling to find badly needed assistance.

“I reach out to different people in wheelchairs," he said, "and that’s how I be figuring out certain things, I just start talking to guys who have been in my situation.”

Evans struck an optimistic note when asked if he thought the bill could attract bipartisan support in the House and Senate.

“We’re not impeding on anybody’s rights, first and foremost,” he said. “The issue is about data collection and information, something I believe that can help us make better policies, and address this critical problem that we have around gun violence.”

Jami Amo, a Columbine survivor, suggested to The Inquirer last year that there ought to be a national clearinghouse that gun violence survivors could consult to discover all of the resources they’re entitled to, with a clear explanation of how to navigate the application processes.

She credited Casey and Evans for taking the lead on an overdue task: establishing baseline information on the needs of gun violence survivors — no matter if they were wounded during overlooked street-corner gunfire or during a mass shooting that attracted national attention.

“It is hopeful. I do see it as a great first step,” Amo said this week. “First step being the operative words here. Now we have to talk about how are we going to expand these programs, make them more accessible, and make them more beneficial to people who need them.”

Amo expressed some concern about how the advisory council will track and rate the effectiveness of existing aid programs.

“You can reach 400 people, but if only one person benefits from any services, then, no, that’s not an effective program,” she said. “That would be a gap that we would need to address.”

The council will be run by the Department of Health and Human Services, and depend on input from gun violence survivors, victim assistance professionals, and federal officials like the attorney general, the assistant secretary for mental health and substance use, and the director of the Office for Victims of Crime.

Casey said the council’s findings will be available online, easily accessible to people who need them most. “Like anything else, unless you have research, it’s hard to make a determination in how to move forward," he said.

In their joint bill, Casey and Evans outline the grim scope of the country’s gun violence epidemic. More than 325 mass shootings were reported in 2018, and firearms are now the second leading cause of death for children and teenagers — and fleading cause of death for black children and teenagers.

About 1,400 people were shot last year in Philadelphia, where gun violence survivors face an average of $46,632 in medical costs, according to the Department of Public Health.

Many, like Frazier, cling to the hope that they won’t always have to scrounge for resources to eke out a normal existence.

“Right now, it would be helpful because I’m still trying to figure out my way, still doing research on my own,” he said of the proposed bill. "Maybe that would make it easier.”