Trump touts ‘super genius’ education at Wharton; former admissions officer saw it differently

James Nolan was working in admissions in 1966 when he got a call from one of his closest friends, Fred Trump Jr. It was a plea to help Fred's younger brother, Donald Trump, get into Penn's Wharton School.

PHILADELPHIA - James Nolan was working in the University of Pennsylvania's admissions office in 1966 when he got a phone call from one of his closest friends, Fred Trump Jr. It was a plea to help Fred's younger brother, Donald Trump, get into Penn's Wharton School.

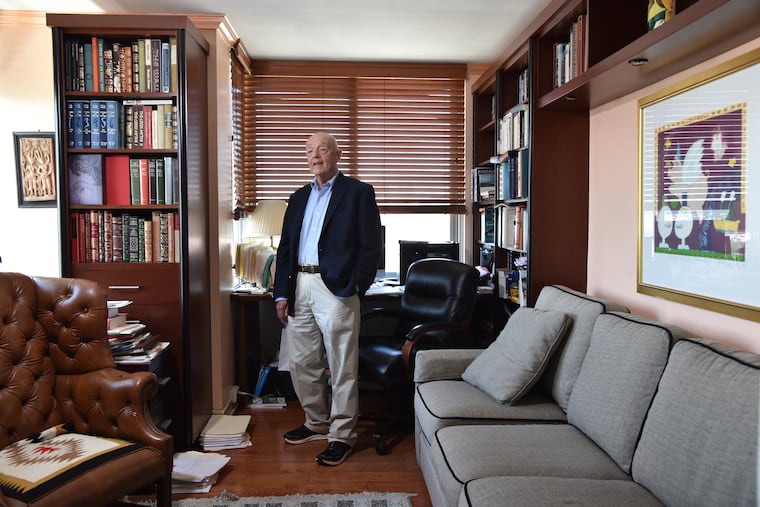

"He called me and said, 'You remember my brother Donald?' Which I didn't," Nolan, 81, said in an interview with The Washington Post. "He said, 'He's at Fordham and he would like to transfer to Wharton. Will you interview him?' I was happy to do that."

Soon, Donald Trump arrived at Penn for the interview, accompanied by his father, Fred Trump Sr., who sought to "ingratiate" himself, Nolan said.

Nolan, who said he was the only admissions official to talk to Trump, was required to give Trump a rating, and he recalled, "It must have been decent enough to support his candidacy."

For decades, Trump has cited his attendance at what was then called the Wharton School of Finance as evidence of his intellect. He has said he went to "the hardest school to get into, the best school in the world," calling it "super genius stuff," and, as recently as last month, pointed to his studies there as he awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to conservative economist Arthur Laffer.

But Trump, who questioned the academic standing of then-President Barack Obama, has never released records showing how he got into the school - or how he performed once he was there. And, until now, Nolan's detailed account of Trump's admission process has not been publicly disclosed.

Nolan, who spoke to The Washington Post recently at his apartment here, said that "I'm sure" the family hoped he could help get Trump into Wharton. The final decision rested with Nolan's boss, who approved the application and is no longer living, according to Nolan.

While Nolan can't say whether his role was decisive, it was one of a string of circumstances in which Trump had a fortuitous connection, including the inheritance from his father that enabled him to build his real estate business, and a diagnosis of bone spurs that provided a medical exemption from the military by a doctor who, according to the New York Times, rented his office from Fred Trump Sr.

At the time, Nolan said, more than half of applicants to Penn were accepted, and transfer students such as Trump had an even higher acceptance based on their college experience. A Penn official said the acceptance rate for 1966 was not available but noted that the school says on its website that the 1980 rate was "slightly greater than 40%." Today, by comparison, the admissions rate for the incoming Penn class is 7.4%, the school recently announced.

"It was not very difficult," Nolan said of the time Trump applied in 1966, adding: "I certainly was not struck by any sense that I'm sitting before a genius. Certainly not a super genius."

The White House did not respond to requests for comment.

Trump, as a young man looking ahead to a career in real estate, viewed entry into a top college as his ticket out of the outer boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn, where his father had built housing largely aimed at the working class. But the idea of going to Penn, as his father wished, was daunting.

Indeed, Trump needed to look no further than his older brother's experience to realize the potential difficulty. Fred Trump Jr. had hoped to go to Penn with his friend Nolan. Fred Trump Jr. and Nolan were best friends, having gone to high school together and spent many hours in the Trump family home in Queens. Nolan provided The Post with a picture that shows him next to Fred Trump Jr. around the time they applied to Penn.

Nolan recalled that Trump's father, Fred Trump Sr., never talked to him during this period, preferring the boys stay in the basement. But the plan for the boys to be roommates at Penn failed: Nolan got in, but Fred Trump Jr. was rejected. The two nonetheless remained close.

Ten years later, in 1966, it was Donald Trump who applied to Penn's Wharton School, having already attended two years at Fordham University in the Bronx., leading to the interview with Nolan. Nolan, who later became director of undergraduate admissions at Penn and now is an educational consultant, said he has not previously been quoted on the record about his role. A 2000 biography, "The Trumps," by Gwenda Blair, cited a "friendly" admissions officer who was friends with Fred Trump Jr., without identifying or quoting him. Fred Trump Jr. died in 1981.

It was common during this period for the children of wealthy and influential people to be accepted ahead of other applicants, especially if the parent made a substantial donation to the school. There is no evidence, however, of such donations in Trump's case.

Records in the University of Pennsylvania archives provided to The Post do not show any donation from Fred Trump Sr. or other family members to the school during the period that Donald Trump applied for admission or was a student. However, some of the donations from that period were made anonymously, so it is not possible to say conclusively whether any Trump family donation was made. The records show donations of $1,000 or more.

The university declined to release records that would explain the decision to accept Trump, or to provide his grade transcripts, citing confidentiality restrictions.

Trump graduated from Penn in 1968. Before long, a legend was born. A 1973 article in the New York Times said Trump graduated "first in his class" from the Wharton School and then quoted his father as saying, "Donald is the smartest person I know."

The claim that Trump was the top student was repeated in a more widely noticed 1976 profile in the Times, once again including his father's quote about being the "smartest person." The Times later published stories that questioned whether Trump was a top student at Penn, noting that transcripts are private.

In fact, Trump's name was not among top honorees at commencement. Nor was he on the dean's list his senior year, meaning he was not among the top 56 students in his graduating class of 366. All that is known for certain is that Trump received at least a 2.0 average, or C, enabling him to graduate. A 4.0 is equivalent to an A.

Penn officials said they are prohibited from releasing Trump's grades unless he allows it.

Trump himself has said that it is crucial to evaluate a candidate's educational background to determine whether he or she is qualified to be president.

For example, in addition to questioning whether Obama was born in the United States, Trump said in a 2011 interview with the Associated Press that he "heard" Obama was "a terrible student, terrible. How does a bad student go to Columbia and then to Harvard?"

Then he challenged Obama to release his college transcripts. "I'm certainly looking into it. Let him show his records."

Trump has not applied his standard to himself. He has declined to release his own college transcripts, and during the campaign, his personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, threatened colleges with lawsuits if his academic records were released.

The idea that Trump was the top performer has persisted partly because the president has continued to let it stand despite the many times it has been debunked. Trump admitted as much last year, saying that he "heard I was first in my class at the Wharton School of Finance. And sometimes when you hear it, you don't say anything. You just let it go."

The common thread in the early stories about Trump was that he had performed so well at Wharton that he was ready to take the family business to a higher level.

Yet Trump is remembered by some classmates as a middling student.

Louis Calomaris, who spent considerable time with Trump during real estate classes, said in an interview that he headed a weekly study group. Trump had attended two or three of the study sessions when, one day in class, the professor announced that the most important thing was to attend his lectures.

"Out of the corner of my eye, I see Trump close his book and he never came to another study group, but he never missed class," Calomaris said.

He recalled Trump standing in his three-piece suit and announcing that he planned to be one of the greatest real estate developers in New York City.

Calomaris, who has worked as a business consultant and restaurateur and taught marketing at the University of Maryland, said that he thought Trump was "a bright guy" but that "he was always lazy - he wouldn't read a book. I never considered him stupid, I considered him opportunistic. . . . He cared about making money, and he knew that the most prestigious school was Wharton, and that worked with his opportunistic nature."

In a 1985 biography about Trump, Jerome Tuccille wrote that Trump hardly viewed his attendance as a priority.

"Donald agreed to attend Wharton for his father's sake," Tuccille wrote. "He showed up for classes and did what was required of him but he was clearly bored and spent a lot of time on outside business activities."

By the time Trump in 1987 released his autobiography, "The Art of the Deal," he had embraced the idea of what he called "truthful hyperbole." The key to promotion, he explained, "is bravado. I play to people's fantasies. . . . People want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular."

Without addressing his class rank or the circumstances of his acceptance, Trump was blunt in his autobiography about the value he found in promoting his time at Wharton.

"Perhaps the most important thing I learned at Wharton was not to be overly impressed by academic credentials," Trump wrote. "In my opinion, that degree doesn't prove very much, but a lot of people I do business with take it very seriously, and it's considered very prestigious. So all things considered, I'm glad I went to Wharton."

As recently as June 19, Trump continued to cite his Wharton background, sometimes in misleading ways. Awarding the Medal of Freedom to Laffer, Trump claimed that "I've heard and studied the Laffer curve for many years in the Wharton School of Finance."

Trump graduated from Wharton in 1968, and Laffer didn’t outline his tax-cutting theory on the back of a napkin until 1974, according to Laffer’s account in a book he co-wrote called “The End of Prosperity.” Thus, studying the Laffer curve during Trump’s time at the school would have been impossible.