Trump made Biden’s presidential transition ‘particularly arduous.’ A revamped process could help.

A new study provides a long list of recommendations to facilitate presidential transitions generally and particularly in case America elects another norms-defying president.

WASHINGTON — When Congress was considering the 2015 presidential transition law, former senator Ted Kaufman, for whom it was named, said the transfer of power “presents us with a moment of potential vulnerability.”

That was years before anyone knew how vulnerable that transfer would become under a president who could not admit he was a loser.

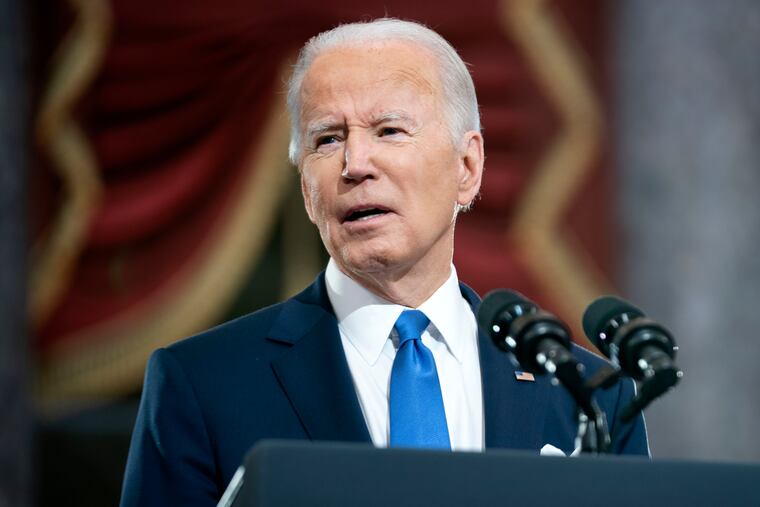

The 2020-21 transition from Donald Trump to Joe Biden was “particularly arduous,” according to a new report, largely because of “the outgoing president’s unwillingness to accept the election results.”

A number of changes to the process could help in the future, both for normal transitions and in case America elects another norms-defying president, according to the study from the good government group Partnership for Public Service and the Boston Consulting Group.

“Trump’s refusal to concede the election led to a delay in ascertainment — the formal decision that initiates the government’s postelection financial and substantive support for the winning candidate,” the report says. “In addition to delaying funding and access to federal agencies, some members of the Trump administration were not fully cooperative with the incoming Biden team, further complicating matters.”

The delay by Emily Murphy, then Trump’s appointed General Services Administration (GSA) boss, resulted in an abbreviated postelection transition period that started almost three weeks late. Instead of beginning immediately after Election Day as usual and lasting about 78 days, the transition was cut to 57 days, according to the study. That exacerbated an already-complex process.

Making presidential transitions, and the services and facilities available to the president-elect’s team, more independent of the previously nonpolitical, perfunctory, election confirmation process was one report recommendation that could facilitate a smooth transfer of power even with a recalcitrant sitting president. “Federal agencies and the White House should share information equitably with still-viable candidates soon after the election irrespective of ascertainment,” meaning before a winner is formally declared, the report suggested.

Securing the services and facilities are critical to the incoming president and vice president. GSA’s extensive list of those items includes “suitable office space appropriately equipped with furniture, furnishings, office and IT equipment, office supplies, parking, fleet vehicles” and payments for office staffs, consultants, travel, printing, postage, and other expenses.

Murphy’s delay interfered with this, and with the ability of President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris to organize their new administration, despite their transition planning that began the April before their November victory.

“Clearly it made everything much more difficult,” Kaufman, cochair of the Biden-Harris transition team, said in an interview. The Delaware Democrat was appointed to the Senate for the remainder of Biden’s term when he resigned to become vice president in 2009.

While the delay was a headache for everyone on democracy’s side, it must have been particularly painful for Kaufman, who wrote the Presidential Transitions Improvements Act that became law five years before Biden’s election. That law directs the “president to plan and coordinate activities to facilitate an efficient transfer of power to a successor President,” according to a congressional summary, and calls for a federal transition coordinator and coordinators in each executive agency.

Trump had no interest in facilitating an efficient transfer of power to Biden.

The transition process in the agencies, however, began months before Election Day. “Prior to the election, the White House met all deadlines required by the [1963] Presidential Transition Act thanks in large part to the leadership of deputy chief of staff Chris Liddell and a small staff,” according to the report. But when Trump’s defeat was evident and he “figured out what was going on, they just put the kibosh on it,” Kaufman recalled. “It was clear the thing just stopped … the whole process came to a halt.”

That was evident in a few instances where “members of the Trump team were outright hostile” to the transition, the report said, citing former Office of Management and Budget (OMB) director Russell Vought and Pentagon officials. Vought did not respond to a request for comment. Liddell, whose transition work the report acknowledged, declined questions.

Christopher Miller, acting defense secretary during the transition, rejected the criticism by email. “The civil servants and political appointees at the DoD bent over backward — like they always do — to guarantee a seamless transition between administrations,” he wrote. “We faced obstacles, politicization and remarkable hostility from the Biden Administration’s Pentagon transition team leadership while providing the most fulsome support and access in modern history.”

OMB was a special case because of its governmentwide influence.

“Contrary to past practice, the Trump White House did not believe it had an obligation to help the incoming Biden team on budget issues during the transition,” according to the report. Quoting a Roll Call article, the study said Vought refused to work with Biden’s team on budget issues, because that “is not an OMB transition responsibility.”

The report said: “OMB’s sparse provision of resources and lack of analytical support did more than just inhibit the Biden team’s development of a budget. It also hindered governmentwide planning for regulations and rule making. As Martha Coven, the OMB agency review team lead, explained, ‘OMB is so crucial to everything that government does that blocking our team there effectively blocked our team elsewhere too.’ ”

OMB would be considered a “service provider to transition teams” under the report’s recommendations because of its key “core of government” responsibilities.

But what can be done if future presidents, like Trump, do not accept their transition responsibilities?

“There’s nothing we can do,” former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, chair of Trump’s 2016 transition team, said during a webinar on the report. “I don’t think from a congressional perspective or any other way … if the president of the United States orders his people not to do certain things, those people then have two choices, either follow the president’s order or quit. But neither one of those things will help make the transition better …

“Whoever is the president is the single most important figure in a presidential transition,” Christie added. “… If presidents want to act in bad faith, then it doesn’t matter what laws are on a piece of paper.”