Republican Jack Ciattarelli is looking to become N.J. governor by reaching moderates without losing the Trump base

New Jersey votes Democrat for president but often chooses Republicans to run the state. If Gov. Phil Murphy wins reelection, he would become the first Democrat to do so since 1977.

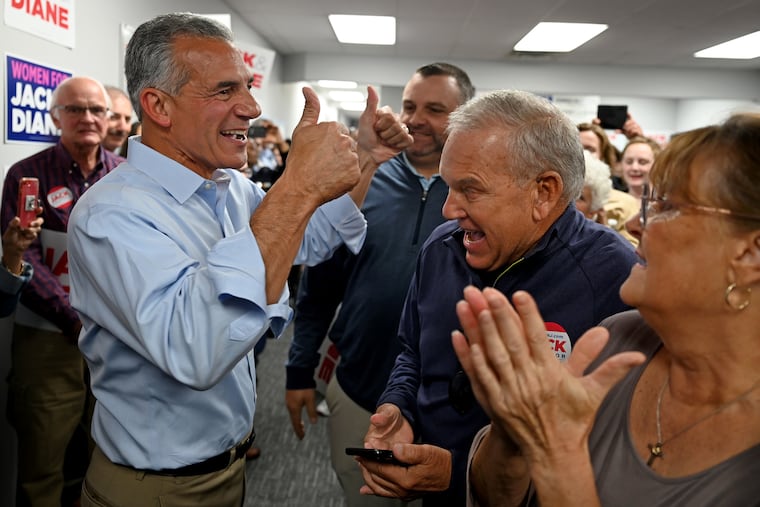

Speaking to a crowd packed into a South Jersey strip mall, Republican Jack Ciattarelli made his standard pitch to voters. He slammed Gov. Phil Murphy’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic, and pledged to make people’s lives more affordable if elected governor.

Then he urged supporters to have faith in the state’s election laws.

“Don’t let anybody stay home because they think we can’t win or because it’s rigged,” Ciattarelli told the audience standing wall-to-wall in the Medford headquarters of the Burlington County GOP last week. “It’s not rigged here in New Jersey. We can win this race.”

It was a rare moment for Ciattarelli, an almost-reference to Donald Trump from someone who’s often tried not to discuss the former president.

But spend time with his supporters, some of whom say voter fraud is a big concern, and Ciattarelli’s reason for mentioning it becomes clear. In his Nov. 2 election bid to oust Murphy, a well-funded incumbent in a state where registered Democrats outnumber Republicans by more than a million and off-year elections can have low turnout, Ciattarelli can’t risk losing one vote.

In interviews last week, Ciattarelli said he just wanted to remind people that the race could be decided by a slim margin, and to reassure those who raised concerns about last year’s mostly vote-by-mail election. He brushed away questions about intraparty divides regarding Trump and the 2020 election.

“It’s true that we have a great many single-issue voters in the Republican Party,” Ciattarelli said. “It’s also true that all Republicans agree on one thing: that Phil Murphy can’t be reelected.”

A former state assemblyman, Ciattarelli has framed the election as a referendum on Murphy by attacking him on taxes, spending and his pandemic response. He’s been campaigning for almost two years, and though early polls gave Murphy double-digit leads, recent surveys show Ciattarelli has gained ground: One last week put Murphy just six points ahead.

Observers agree Ciattarelli needs votes from the state’s 2.4 million independents and maybe some Democrats to win, but Trump’s influence lingers, even in a state that rejected him by 16 percentage points last year. So to capture more moderate votes, Ciattarelli has gone searching for what he describes to conservative audiences as “wiggle room.”

Ciattarelli once called Trump a “charlatan,” but later said his policies were good for the country. He spoke at a “Stop the Steal” rally last November, an event where a Confederate flag was displayed, but he doesn’t dispute that Joe Biden won the election (and says he was unaware of the theme of the rally). He opposes mask mandates in schools, a position that’s popular with those who attend his town hall meetings but that polls suggest is not supported by most New Jerseyans. He says he’d loosen gun laws, whereas Murphy has further restricted them. He’d roll back LGBTQ curriculum in schools and said “we’re not teaching sodomy in sixth grade,” a statement that advocates called offensive.

» READ MORE: New Jersey hasn’t reelected a Democratic governor in 44 years. Gov. Phil Murphy says he’ll break the curse.

Ciattarelli also supports driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants. He says he’d sign a law to protect abortion rights in New Jersey, but one with restrictions including parental notification. After initially refusing to define “white privilege” in a radio appearance, he later acknowledged in a televised debate with Murphy that white people have had advantages others have not.

Mike DuHaime, a GOP strategist who worked for former Gov. Chris Christie, said that while Democrats are essentially aligned on major campaign issues, Ciattarelli has to work harder to find common ground.

“We don’t normally have to worry about unifying our party,” DuHaime said. “This year we have these culture wars, these mask debates, and that’s counterproductive to that unity.

“When it comes to masking and vaccines,” he added, “how do you find an answer that both sides find satisfying?”

A ‘Jersey guy’

Ciattarelli, 59, is a CPA and entrepreneur who founded a medical publishing company. He was a councilman in Raritan and a commissioner in Somerset County, where he lives. He and his wife, Melinda, have four children.

He campaigns in an energetic, backslapping style. Though he’s struggled with name recognition, he now tells a joke about being recognized in a gas station bathroom by someone who saw his commercials. Many who meet him walk away with a positive impression, and observers from both parties agree he’s made the race closer than it once appeared.

Murphy and his campaign have painted Ciattarelli as an extremist in lockstep with Trump, but he was known as a moderate in Trenton. He ran for governor four years ago with some of the same ideas as now: to fix New Jersey’s finances, and overhaul property taxes and school funding. He said he wasn’t opposed to raising taxes on millionaires — a law passed last year that Murphy touts as a signature achievement. Ciattarelli, who now says he’d cut taxes on high earners, lost the 2017 primary election to Lt. Gov. Kim Guadagno.

Despite voting Democratic in presidential elections, New Jersey often chooses Republican governors. If Murphy wins a second term, he would become the first Democratic governor to do so since 1977.

Murphy began the year with a wind at his back. His approval ratings skyrocketed early in the pandemic, and he has accomplished many of his popular legislative goals, like raising the minimum wage and enacting paid sick leave. Ciattarelli has attacked the coronavirus-related business restrictions imposed last year, the state’s high death rate in long-term care homes and Murphy’s mask and vaccine mandates. But polls indicate that voters still support Murphy’s crisis response, even with the race tightening.

Taxes and government dysfunction have been the path to election for Jersey Republicans, but they aren’t at the top of the list for some voters this time, said Ben Dworkin, director of the Rowan Institute for Public Policy and Citizenship.

“COVID shrouds everything,” Dworkin said. “Everything else is filtered through that, so the traditional issues that Republicans would run on don’t resonate as much.”

Drawing a contrast with Murphy, an ex-Goldman Sachs millionaire, Ciattarelli casts himself as a “Jersey guy” who summers on the Shore and whose mother disciplined him and his brothers with a wooden spoon. Quoting Ronald Reagan from his 1980 presidential campaign, he asks people if they’re better off than they were four years ago.

“It’s not a job I need. It’s a job I want,” he told an audience at a town hall in Gloucester County in August. “I’m tired of this state being junior varsity.”

Ciattarelli and his running mate, former State Sen. Diane Allen, have also used scandals in Murphy’s 2017 campaign to paint him as anti-woman.

» READ MORE: Diane Allen was a moderate N.J. Republican. She sounds a bit different running for lieutenant governor.

A former state official, Katie Brennan, said that a Murphy campaign aide raped her in 2017 and that her reports to Murphy’s staff were ignored. Former top strategist Julie Roginsky later said the campaign was toxic; she and several women accused Murphy and campaign officials of not responding adequately to complaints. Murphy has apologized to those he “failed” and hired a human relations firm to oversee the workplace culture for this year’s campaign.

When Ciattarelli’s campaign released an ad featuring footage of Brennan testifying to a state legislative panel about her assault, Brennan was outraged.

“Survivors are not your props. We are not your political pawns. To use me as such, without my consent, is disrespecting survivors. It is disrespecting women,” Brennan posted on Twitter. She asked the campaign to take down the ad. It stayed up.

Taxes and spending

One of two governor’s races this year, New Jersey is often watched as a harbinger for broader political shifts: Chris Christie’s victory in 2009 heralded the next year’s Republican wave.

The numbers are getting harder for the GOP. Even Somerset County, the longtime Republican stronghold where Ciattarelli lives, went blue last year. At a fund-raiser hosted for Ciattarelli in his hometown of Hillsborough last month, guests mingled on a manicured lawn, some lamenting the challenge for a politician like Ciattarelli. Most weren’t talking about masks or voter fraud.

“I just want spending under control,” said Paul O’Dwyer, 63, from Bridgeton. “Jack’s a CPA, I’m a CPA.”

Ashley Cockburn, 63, Ciattarelli’s neighbor for more than two decades, said he’s dismayed by what he sees as Murphy’s unwillingness to address the state’s high taxes.

“I love New Jersey and I want to stay in New Jersey,” he said. “This guy ran it into the ground. We need somebody with a plan.”

Ciattarelli says he would lower property taxes by shifting the burden of special education spending to the state, restoring state aid to suburban schools and freezing increases for seniors, among other proposals. Murphy, who has said he inherited a financial mess from the Christie administration, counters that Ciattarelli’s plan would shortchange underserved districts by redistributing their funding.

Election doubts

Though Ciattarelli assured his supporters in Medford last week that the election would be conducted properly, several attendees were skeptical. Others repeated false claims of widespread voter fraud that have been spread by Trump.

Val Gallagher, a 48-year-old Realtor who lives in Moorestown, said she’s a former independent who once supported Barack Obama but now votes Republican. She believes elections are “rigged” — “All of them” — but she’s voting for Ciattarelli because she likes him, and thinks he’ll represent her interests.

“It’s really hard to get people to tell the truth at this point,” she said. “It’s hard to trust the government.”

Before Ciattarelli won the June primary, 69-year-old Bill Simpkins said he and his wife backed GOP candidate Hirsh Singh, who ran on an extreme pro-Trump platform. Asked if it troubled him that Ciattarelli doesn’t share his belief that Trump won the 2020 election, Simpkins paused.

“It bothers me a little bit,” he said. “But I still support him.”