N.J. was going to have paper-based voting machines more than a decade ago. Will it happen by 2020?

The state was poised to lead the nation. Now it trails other states — and has no real plans to catch up.

New Jersey was once poised to become a national leader in election and voting security. Instead, it now lags most states — including Pennsylvania and Delaware — by relying on aging, paperless machines that experts say are vulnerable to attack and can’t be properly audited.

There are no statewide plans to buy new machines; nor is the state urging counties to buy new systems, in contrast to Pennsylvania, where Gov. Tom Wolf has ordered all 67 counties to have new machines by next year’s primary election.

“We are doing what we can with the funding that we have and the situation that we’re in,” said Robert Giles, who heads the state’s Division of Elections. The challenge, he said, is funding. Counties are left to their own initiatives.

But the current machines are nearing death. The money will have to come from somewhere, said Jesse Burns, head of the League of Women Voters of New Jersey.

“Time, it has run out. So there’s no more kicking it down the road,” she said.

New Jersey was once at the vanguard of voting security. In the mid-2000s, it became an issue thanks to a major lawsuit from voters. The state Legislature in 2005 passed a law requiring that machines allow voters to verify paper ballots by 2008, then required audits of those paper trails. It even set aside $20 million in funding to retrofit machines to print records.

Instead, the governor took back the money as the recession struck; lawmakers suspended the requirement to buy new machines; no funding has materialized since.

Now, as the 2020 elections draw ever nearer, a handful of counties are replacing their machines, some of them two decades old. Others will continue to rely on current systems, waiting for federal or state funding before undertaking the costly, time-consuming upgrade to protect citizens’ votes.

“You’re going to see some counties moving forward very quickly, and some counties you’re going to see dragging their feet a little bit,” Burns said. Ultimately, she said, “I think the counties are going to be paying for it. … I don’t see money magically appearing. It could be, maybe, a budget priority. I don’t know.”

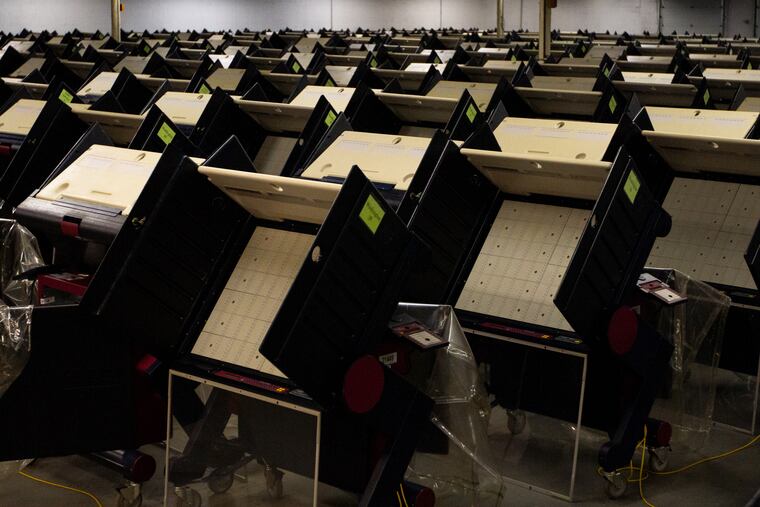

Most counties in New Jersey use electronic machines on which the entire ballot is displayed and voters press buttons to make their selections before the votes are stored electronically. With strict protocols in place, elections officials, including Giles, emphasized that those procedures help prevent attack.

“We’re in pretty good shape,” said Phyllis Pearl, the Camden County supervisor of elections. “I don’t believe the integrity of elections is being compromised.”

The problem, security experts say, is that those machines don’t leave a paper record of each vote cast in case something does happen: A hack alters vote totals, say, or an electronic failure corrupts the record. Experts generally agree that the solution is a voter-verifiable paper audit trail.

That also improves confidence among voters, allowing them to see their vote and not simply trust that a machine recorded it accurately, said Lawrence Norden, an attorney and voting-rights expert at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University and co-author of a report last week on the state of voting machines nationwide.

“There’s a danger that people lose faith that their vote is going to be counted and that they matter,” he said. “For the system to work, people need to believe in it and they need to participate in it.”

Unlike in Pennsylvania, a battleground state in presidential elections, New Jersey is generally a lock for Democrats. There’s less scrutiny — and pressure.

“A lot of it just has to do with public demand for something to happen,” Norden said. “Too often, the attitude of legislators is like, ‘Come back to me when the crisis has actually hit.’ ”

In the years since New Jersey lawmakers suspended the statewide paper-trail requirement pending the availability of funds, little has changed. Most counties are still using the same machines they used then, but there’s been movement recently.

Warren County, the only one of the 21 that already had machines with a paper trail, has bought new machines that also produce paper records. Union and Warren Counties have purchased new machines, and Middlesex and Gloucester Counties are in the process.

In November, pilot tests were run in a few towns in Essex, Gloucester, and Union Counties; Mercer and Warren Counties ran pilots in school elections after that.

“We really did like them,” said Stephanie Salvatore, the Gloucester County superintendent of elections.

The county’s current machines were purchased in 1999 and intended to be used for about 20 years, Salvatore said, so the county for a few years now has been planning replacements at a cost of around $4 million.

Gloucester County’s pilot program, like a few others, was funded with a portion of federal election money. Giles said the Division of Elections can do little more than encourage those pilots and continue to certify machines that leave paper trails. It all comes back to funding, and Congress and the state Legislature aren’t providing it.

The Brennan Center estimates the total cost at between $40.4 million to $63.5 million.

Will that money come?

Gov. Phil Murphy’s office referred comment to the office of the secretary of state, which set up the interview with Giles — who said he could not speak to policy because his job is to administer it, not create it.

Similarly, State Senate President Steve Sweeney (D., Gloucester), who cosponsored the legislation suspending the paper-trail requirement, directed questions to Sen. Jim Beach (D., Camden), who “suggested getting in touch with Bob Giles at the Division of Elections,” a spokesperson said.

“I just don’t see the action on the state level happening,” said Renee Steinhagen, head of New Jersey Appleseed, the Newark-based branch of the public-interest law coalition.

Steinhagen said she was focusing instead on the county elections officials who actually buy machines and run elections.

If she can get their attention.

When the Brennan Center was putting together last week’s report on the state of voting machines, Norden said, staffers reached out to officials in all 21 counties.

None responded.