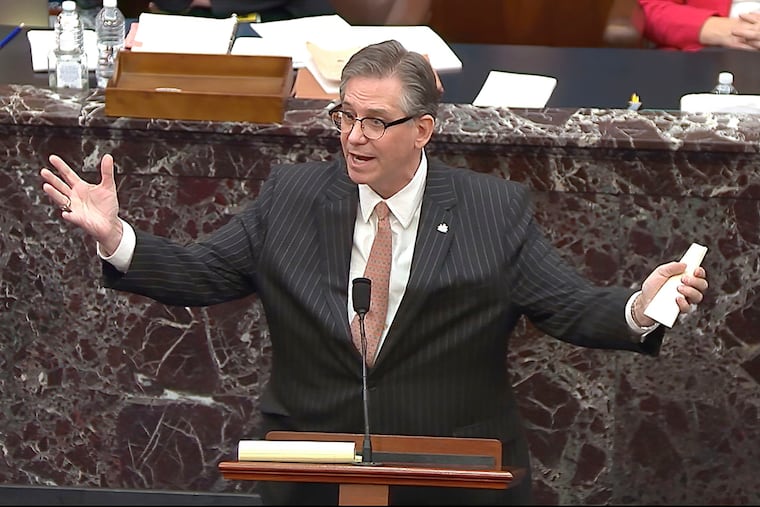

Bruce Castor had a big spotlight to open Trump’s impeachment defense. It didn’t go well.

Castor’s rambling presentation had the internet howling, some GOP senators scratching their heads, and Trump “nearly screaming at the television.”

Under the biggest spotlight of his career, Bruce L. Castor Jr. stood in the well of the U.S. Senate and delivered the opening salvo of his defense in the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump.

By most accounts, it did not go well.

In a meandering, 50-minute speech Tuesday, the former Montgomery County commissioner and district attorney heaped praise upon the senators who will serve as jurors, calling them “extraordinary people” and “patriots.” He digressed into folksy anecdotes from “little Bruce’s” childhood in suburban Philadelphia. And he mystified his audience with an extended explanation on the difference between murder and manslaughter.

What he spent precious little time on was the central question of the day: Is it constitutional for a former president to face an impeachment trial?

And by its end, Castor’s rambling presentation had the internet howling, some GOP senators scratching their heads, and, according to CNN, Trump “nearly screaming at the television.”

“I’ve seen a lot of lawyers and a lot of arguments and that was … not one of the finest I’ve seen,” Sen. John Cornyn (R., Texas) said.

Even the right-wing cable channel Newsmax cut away from Castor to a confused-looking Alan Dershowitz, who defended Trump in his last impeachment trial.

» READ MORE: Searing images of the Capitol attack and arguments over the Constitution open Trump’s impeachment trial

“I have no idea what he’s doing,” Dershowitz said. “There is no argument. I have no idea why he’s saying what he’s saying.”

At least one person gave Castor a five-star review: Castor himself.

“I thought we had a good day,” he told reporters outside the Senate chamber.

That enduring confidence and Castor’s penchant for long-winded circumlocution should be familiar to anyone who’s followed his decades-long career in Pennsylvania politics and law.

When he testified in Bill Cosby’s sexual-assault case five years ago — about a non-prosecution agreement he maintains he signed with the former comedian — he began with a 20-minute recitation of his career and the awards he had won.

» READ MORE: More Philly lawyers are on Trump’s impeachment defense team and one sued the president last year

“There would be so many,” he told the judge, it might be easier to submit a resume.

In interviews, Castor frequently recounts tales of his courtroom victories during his heyday as Montgomery County’s hard-charging DA.

And as he read notes hastily scratched on a yellow legal pad Tuesday, he appeared at times to be pining for those more familiar stomping grounds.

“My name is Bruce Castor, and I am the lead prosecutor — err — lead counsel for the 45th president of the United States,” he said, before apologizing. “I was an assistant DA for such a long time that I keep saying prosecutor, but I do understand the difference.”

He eventually moved on to a somewhat more focused defense: Allowing the impeachment trial — which he argued is unconstitutional and seeks to hold Trump accountable for speech protected by the First Amendment — to proceed would “open the floodgates” to more partisan use of impeachment in the future.

“The political pendulum will shift one day,” he said. “And partisan impeachments will become commonplace.”

» READ MORE: Bruce Castor’s impeachment trial speech spawns memes and confusion

But by then, Castor had already lost much of the room. Some GOP senators didn’t mince words when speaking to reporters afterward.

“I couldn’t figure out where he was going,” said Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R., Alaska). “He spent 45 minutes going somewhere, but I don’t think he helped with us better understanding where he was coming from on the constitutionality of this.”

Sen. Bill Cassidy (R., La.) described the presentation as so bad that it prompted him to change his vote. He broke with most of his party and threw his support behind allowing the trial to continue, after previously voting that it’s unconstitutional because Trump is no longer in office.

“Did you listen to it?” he said of the defense presentation. “It was disorganized, random ... [and] they did not talk about the issue at hand. If I’m an impartial juror, and I’m trying to make a decision based upon the facts as presented on this issue, then the House managers did a much better job.”

That may have been part of the problem. Castor hadn’t originally planned to lead off Trump’s defense Tuesday, deferring that position to his cocounsel on the case, Alabama lawyer David Schoen.

But after a taut, emotional appeal from the lead Democratic House impeachment manager — featuring a startling 13-minute video recap of the Jan. 6 Capitol attack — the defense team reshuffled its plans.

» READ MORE: 5 things to know about Bruce Castor, the Montgomery County lawyer now repping Donald Trump

“I’ll be quite frank with you,” Castor said on the Senate floor. “We changed what we were going to do on account that we thought the House managers’ presentation was well-done.”

No matter what senators think of Castor, it’s unlikely to change the outcome of the trial. Democrats need 17 Republicans to vote to convict, and only a handful have suggested they’re open to doing so.

Still, sources within Trump’s defense team said the choice to put the folksier Castor up before the pugnacious Schoen was an attempt, as one put it, to “lower the temperature in the room.”

But, as a strategy, did it work? Sen. Ted Cruz (R., Texas), one of Trump’s most ardent supporters, paused for several seconds before finally answering that question.

“I don’t think the lawyers did the most effective job,” he told reporters. “But I’ll leave it to others to fill out the scorecard on that front.”

Staff writer Jonathan Tamari contributed to this article.