Joe Biden designates Carlisle boarding school that abused Native children a federal monument

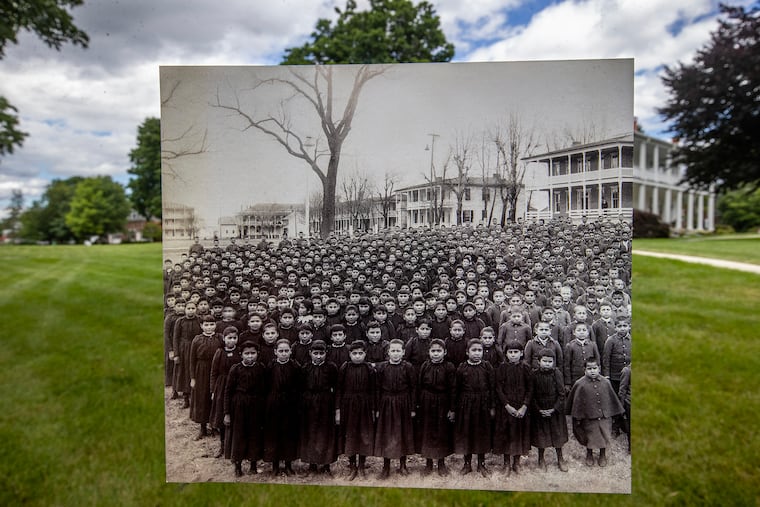

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the flagship operation of federally funded, off-reservation boarding schools that forcibly took Native American children away from their homes.

President Joe Biden on Monday designated a federal monument in Carlisle, Pa., at a former boarding school that mistreated Native American children in an attempt to assimilate them — and served as a model for similar institutions across the country.

From 1879 to 1918, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the flagship operation of federally funded, off-reservation boarding schools that forcibly and coercively took Native American children away from their homes to erase their cultural identities, names, languages, traditions, religions, and family ties. The philosophy for the forced assimilation at the school — which included beatings and deadly epidemics — was to “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

The Carlisle model was replicated in more than 417 federally supported boarding schools over the next century, along with others that operated without government support, according to the White House.

While the schools were seen by white society as a more progressive method than outright killing Natives, nearly 1,000 children, including more than 180 in Carlisle, have been recorded as dying while attending the at-times deadly schools, and the number is likely much higher, according to the White House.

Biden held a summit with tribal leaders on Monday. In October, he provided formal apology on behalf of the United States for the schools.

Louellyn White, a Kanienʼkehá:ka (Mohawk of Akwesasne) descendant of Carlisle, whose grandfather and other family members were sent to the Carlisle school, said the recognition “is a long time coming.”

White teaches Indigenous Studies at Concordia University in Montreal and has been involved in historic preservation and repatriation efforts at the Carlisle school, where she said indigenous children remain buried on school grounds — as well as across Pennsylvania.

“This kind of recognition and acknowledgment will help to educate the public, create increased awareness, and contribute to healing Indigenous communities,” she added.

The site of the former boarding school is now located within the United States Army’s Carlisle Barracks, which is home to the U.S. Army War College and, according to the proclamation, one of the oldest military installations in the country. In 1863, Confederate troops torched buildings on the campus that served as a central supply center for the Union Army in the Civil War before the government rebuilt the barracks for the Army before it became a boarding school.

It was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1961 and added to the National Register of Historic places in 1966, according to the White House. The monument boundaries align with those of the landmark, and the new designation “will help ensure this shameful chapter of American history is never forgotten or repeated,” according to the White House.

The monument will be managed by the National Park Service and U.S. Army, and both entities will work in the coming years to develop national park programming at the site in consultation with tribes. The site includes 24 historic structures that were part of the school’s campus, as well as gateposts that were constructed by children at the boarding school.

Biden’s proclamation acknowledged that Native American children were taken to these schools and stripped of their languages, religions, and cultures, as well as subject to physical and sexual abuse, compulsory labor, corporal punishment, and insufficient nutrition and medical care.

At Carlisle, they were forced to study Catholicism and prohibited from speaking their Native languages. Staff at the schools cut their hair and forced them to give up their traditional names and clothing. The proclamation includes quotes from natives recounting the trauma of having their hair forcibly cut off when they arrived at the school, including Zitkala-Sa, a Dakota woman from the Yankton Sioux Reservation, who said she was dragged from her hiding spot under a bed and tied to a chair.

“Then I lost my spirit. . . . In my anguish I moaned for my mother, but no one came to comfort me . . . for now I was only one of many little animals driven by a herder,” she said.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American cabinet secretary, whose great grandfather and grandparents were taken from their families and taken to boarding schools, has focused on documenting the schools through the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. She said she launched the effort to make sure people can learn about the intergenerational impacts of the policies surrounding the schools.

“No single action by the federal government can adequately reconcile the trauma and ongoing harms from the federal Indian boarding school era,” said Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna tribe. " … “This trauma is not new to Indigenous people, but it is new for many people in our nation.”

The proclamation acknowledges that the concept of using education and separation to control native children goes back centuries to early colonial times.

The 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act ended the forced assimilation policies that permitted the boarding schools, but the government never fully investigated the system until the Biden administration, the Associated Press reported.

“For almost 40 years, the Department of the Interior operated the Carlisle School as an Indian Industrial School, melding the approach of incarceration with assimilative education policies,” the proclamation says.

The office of U.S. Rep. Scott Perry, a Republican whose district includes Carlisle, did not immediately respond to a request for comment.