Marsy’s Law ballot question will appear in Pa., but state Supreme Court says votes won’t be counted for now

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court upheld a ruling that said it would have “immediate, profound, and in some instances, irreversible, consequences on the constitutional rights of the accused."

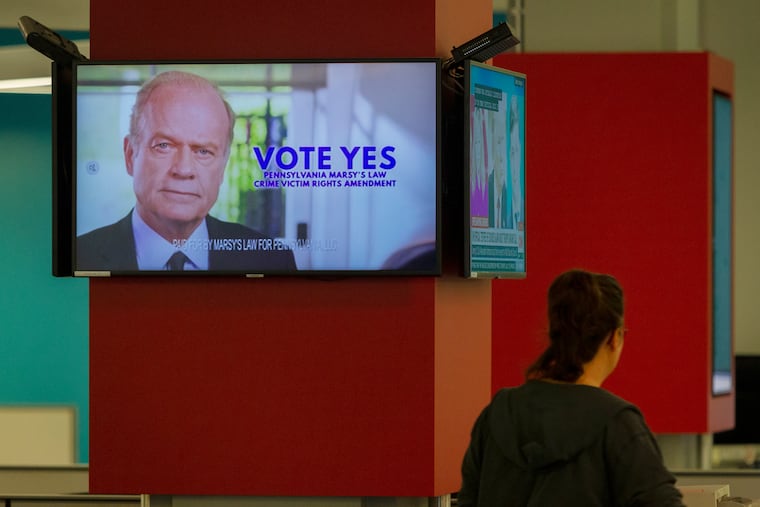

If you’ve turned on network television in Pennsylvania in the last several weeks, you’ve probably been treated to political advertising in the form of the actor Kelsey Grammer telling the story of how, after his father was shot and killed, he found out about the killer’s release through a tabloid.

The actor and other advocates have been drumming up support for Marsy’s Law, a proposed constitutional amendment that Pennsylvania voters will see on election ballots on Tuesday — but those votes won’t be counted or certified until state courts decide whether Marsy’s Law is constitutional.

A divided state Supreme Court on Monday upheld a lower court ruling by Commonwealth Court Judge Ellen Ceisler, who last week ruled partially in favor of the League of Women Voters and others who challenged the proposed amendment. Ceisler concluded Marsy’s Law would, if passed, have “immediate, profound, and in some instances, irreversible, consequences on the constitutional rights of the accused and in the criminal justice system.”

The decision represents the first time a state court has delayed the certification of votes to approve a constitutional amendment. Now, the legal battle turns to whether the law itself is constitutional.

Here’s a primer on what Marsy’s Law is, and why some say it could have unintended consequences.

What’s the TL;DR?

If you find it “too long, didn’t read,” here’s the essence: You’ll be able to vote “yes” or “no” on the law, which guarantees crime victims and their families rights, including:

Notice of developments (such as release and parole) and to be told about plea deals before they’re offered.

To give statements in proceedings including release, plea, sentencing, and parole.

To refuse an interview or discovery request made by, or on behalf of, the accused.

Victims already have these rights under Pennsylvania’s relatively strong victim’s rights law. But Marsy’s Law would enshrine them in the state Constitution, a move advocates say would give victims standing in court.

Jennifer Storm, the state’s victim advocate and a Marsy’s Law supporter, said that although victims have strong rights under current law, “there’s no enforcement mechanism.” Having a standing in court would allow victims to, for example, petition a judge to reconsider a sentence if they weren’t notified of a plea arrangement.

Why is it on the ballot?

Constitutional amendments must pass both chambers of the state legislature in consecutive sessions (that already happened with bipartisan support), be signed by the governor (that happened, too), and be approved by a majority of voters. Here’s what Pennsylvanians will see on the ballot Nov. 5:

Has this been a thing in Philly?

Several crime victims or families of murder victims have claimed they’ve been kept out of the loop by prosecutors under District Attorney Larry Krasner, a former criminal defense lawyer who took office in January 2018. Last year, the office violated the state Crime Victims Act by failing to notify the victim of an attempted robbery that his attacker had been offered a plea deal. The office at the time said “honest mistakes” were made by the prosecutor.

» READ MORE: Philly judge lets AK-47 gunman withdraw guilty plea in shooting of beer deli owner

Storm said it’s happened a lot in Philadelphia historically, not simply under Krasner. She said that although some failures to keep victims apprised of case movement has been “intentional and convenient,” it’s also due to the “volume of cases” the office handles.

Although Krasner had signaled some support for Marsy’s Law last year, spokesperson Jane Roh said Tuesday that the district attorney doesn’t back the current language of the amendment, which his office “endeavored to help modify” because it could open up the city to litigation. She said the office would continue to work toward “legislative modifications” to prevent or discourage Marsy’s Law-related lawsuits against municipalities.

Who is Marsy?

Marsy is short for Marsalee Nicholas, a California woman who was killed by her ex-boyfriend in 1983. A week after her death, her mother and brother ran into her killer in the grocery store. They had no idea he’d been released on bail.

That brother is Henry Nicholas, now a billionaire and the founder of Broadcom, an international software firm. He made it his personal mission to advocate for victims’ rights, spending more than $70 million to back implementation of Marsy’s Law in every state since the first version was adopted in California in 2008.

Last month, Nicholas took a plea deal to avoid prison on drug trafficking charges.

Is that why I’m seeing so many ads about this?

Yes. Henry Nicholas has poured millions into these campaigns across the country. Marsy’s Law for Pennsylvania, funded exclusively by Nicholas’ foundation, spent nearly $3.5 million over the last year, the majority on advertising, campaign finance reports show. That’s more than twice what all the state Superior Court candidates — the only statewide race this cycle — spent in the same period, combined.

Thirty-five states already have constitutional rights for crime victims, with about a dozen having passed some or all of Marsy’s Law. Others already had such language in place. Crime victims in New Jersey have an array of rights under both an extensive state law and a constitutional amendment. There are also Marsy’s Law efforts underway in Wisconsin, Idaho, and Maine.

What was the ACLU concerned about?

Opponents say in court papers that Marsy’s Law “will change virtually every aspect of our criminal justice system” and is being presented to voters as one change, not many changes, leaving them unable to vote for or against different aspects. They also argue that if Marsy’s Law passes, it would “wreak havoc” on the criminal justice system and create a financial and administrative burden in the courts.

Elizabeth Randol, legislative director of the ACLU of Pennsylvania, said equating the rights of victims with those of defendants misunderstands the point of constitutionally protecting the accused, who face a loss of liberty. She said even classifying someone as a “victim” before a conviction infringes on due-process rights.

Randol said the ACLU is also concerned about how different judges would interpret these rights, as well as whether requiring notification of victims could keep an accused person incarcerated for longer than need be.

“The fact that there are this many questions,” she said, “to me says this is too much of a live wire to introduce into a system that has been structured since the Magna Carta.”

Every state that implemented Marsy’s Law has faced a court challenge. Two were successful: In Kentucky, the courts held the ballot question was too vague, and in Montana, the measure was voided for making more than one constitutional amendment at a time.

What do Marsy’s Law supporters say?

Storm emphasized that Marsy’s Law wouldn’t grant equal rights to victims — they wouldn’t be parties in the case, so they can’t themselves appeal decisions — only equal enforcement of the rights they do have.

Jennifer Riley, director of Marsy’s Law Pa., contended that Marsy’s Law has been implemented smoothly in other states without infringing on the due process rights of the accused.