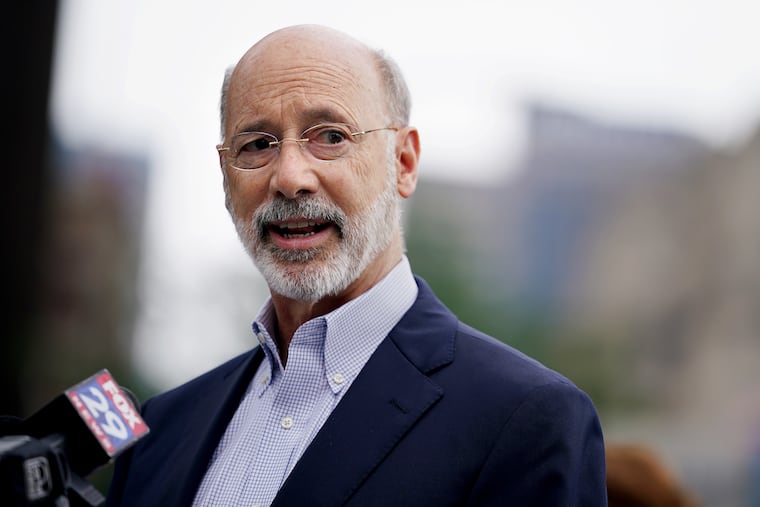

Wolf vetoes permitless gun bill pushed by Pa. Republicans, calls it ‘dangerous’

The governor called the bill “dangerous.” His veto comes amid rising gun violence in Pennsylvania’s cities, particularly Philadelphia, and political finger-pointing over blame.

HARRISBURG, Pa. — Gov. Tom Wolf followed through on his veto threat Thursday, rejecting Republican-penned legislation to allow people to carry a firearm openly or concealed, without a permit, adding to his total for Pennsylvania’s chief executive with the most vetoes in more than four decades.

Wolf, a Democrat, called the bill “dangerous.” Wolf’s veto comes amid a tide of deadly gun violence in Philadelphia, the state’s largest city, and political finger-pointing over blame.

Wolf has said it is a top priority to address what he says is a gun violence crisis affecting largely minority communities, but the Republican-controlled Legislature has rejected nearly all his proposals.

» READ MORE: Amid a spike in shootings, Pa. legislators are giving us the kinds of gun laws that we don’t need | Opinion

The bill he vetoed Thursday would have removed the requirement that gun owners get a permit to carry a gun that is concealed, such as under clothing or in their vehicle’s glove box. It also would have wiped out a law, applying only to Philadelphia, that requires gun owners to get a permit to openly carry a firearm in the city.

Pennsylvanians otherwise are generally allowed to openly carry loaded firearms, although the law is silent on it.

According to online state records, Wolf has penned his 52nd veto with 13 months left in his second term, more than any other governor since Milton Shapp, who left office in 1979. Wolf has passed Democrat Robert P. Casey, who compiled 50 vetoes.

The Legislature — controlled by Republicans since Wolf took office in 2015 — has never overridden a Wolf veto, with Democrats protecting Wolf and preventing Republicans from gathering the necessary two-thirds majorities in both chambers.

Friction over the governor’s broad use of executive authority to respond to the pandemic has played a role, with Wolf taking a veto pen to about a dozen COVID-19-related bills passed by lawmakers.

Wolf was surprised to hear Thursday that he has more vetoes than any governor since Shapp.

Democrats and Republicans disagree on what is fueling the governor’s growing stack of vetoes, but Wolf took the high road.

“I was looking over the past seven years, and it’s really amazing what we’ve gotten done together,” Wolf said. “I know people are talking about the polarization in politics, but here in Pennsylvania ... we’ve chosen to focus on those areas where we can agree, so we’ve gotten a lot of substantive things done.”

Senate Minority Leader Jay Costa, D-Allegheny, wasn’t so kind.

Republicans send bills to Wolf without trying to negotiate, knowing full well that Wolf will veto it, but it serves their purposes to show their base voters they are working on issues and shift blame to Wolf as the impediment, Costa said.

“It is political theater, and they’re playing it out in front of their base of supporters,” Costa said.

Republicans blame what they say is Wolf failing to engage with lawmakers, compromise or negotiate.

“This governor hasn’t figured out how to work with the Legislature,” Senate President Pro Tempore Jake Corman, R-Centre, said last month.

Costa disputes that, saying “negotiating is not one party, Republicans, telling Democrats and the Democratic governor ‘this is how it’s going to be.’”

In any case, the result, Corman and others say, has been for the sides to seek alternatives to lawmaking.

The governor has often taken action through executive order or drafting regulations, and lawmakers taking action through drafting proposals to amend the state constitution. Those can’t be vetoed by Wolf.

Republican lawmakers now are trying, through proposals to amend the constitution, to give them more control over a governor’s powers to make permanent policy through regulation or executive order.

One would strip the authority of a governor to veto a resolution passed by lawmakers to block a proposed regulation. Currently, the governor can veto such a resolution.

The other would limit the effect of an executive order to 21 days, unless lawmakers agree to extend it.