Are Philly’s suburbs the key to the White House? Why Trump and Harris are renewing their focus on the collar counties.

The campaigns of both former President Trump and Vice President Harris are renewing their focus on the collar counties.

In just three days, Vice President Kamala Harris, former President Donald Trump, and their running mates doubled their cumulative trips to the Philadelphia suburbs from three to six.

The intense renewed focus on Philly’s collar counties shows no signs of slowing as both campaigns shift to a new phase of the presidential race — one aimed at getting their base voters to the polls rather than persuading new supporters.

The suburbs, home to around 30% of Pennsylvania’s voters — with a population that exceeds that of Chicago — will be key for both candidates on Nov. 5 as they look to run up their statewide totals in a race expected to be decided by razor-thin margins.

“There’s so much voter turnout at stake in the suburbs, and the southeast region of Pennsylvania is just really important and key, I think, for both campaigns,” Delaware County Council Chair Monica Taylor, a Democrat, said. “Now, as we’re getting to those GOTV [get out the vote] efforts, coming to the suburbs to make sure everything is strong here.”

The collar counties powered President Joe Biden’s victory in 2020, and promise to play a similarly pivotal role this election.

On Monday, Trump made his first visit to deep-blue Montgomery County for a town hall — which turned into a bizarre playlist party. His running mate, Ohio Sen. JD Vance, followed that lead Tuesday, visiting the populous collar county for a town hall with the right-wing Moms for America group.

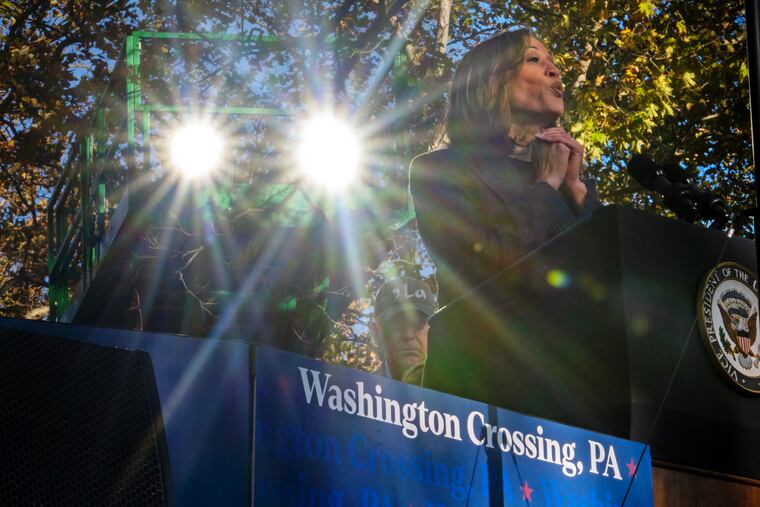

And on Wednesday, their opponent, Harris, held a rally in purple Bucks County aimed at Republican voters who had soured on Trump. It was her first trip to the Philadelphia suburbs since becoming the nominee.

Trump, Harris, and their surrogates have been ping-ponging across the state in the last several months, but their return to the Philadelphia suburbs signals a shift in the final weeks of the race from persuasion to getting out the vote.

They are likely to continue to narrow in on the collar counties in the coming weeks. Harris is scheduled to hold an event Monday in Chester County and return for her CNN town hall in Delaware County on Wednesday. And a spokesperson for Trump said the former president will work the grill at a suburban McDonald’s this weekend.

“This is now focused on two things, your base and anyone adjacent to it,” said Guy Ciarrocchi, a GOP strategist from Chester County. “I don’t think either of them are under any illusion that any one appearance is going to move 50,000 votes. But you’re at a point, in a state that’s going to be decided by under 50,000 votes, you come in and move 5,000, it was worth it.”

Driving out the base

For Trump, a spokesperson for the campaign, who asked for anonymity so he could discuss tactics, said his staffers will spend the next several weeks setting up bus tours and town halls. Those events will focus on issues relevant to collar-county voters.

In some cases, the message will appeal to Jewish voters, the spokesperson said, with references to the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attack in Israel, antisemitism, and “clear anti-Israel elements” among Democrats. “There are a lot of Jewish voters in the collar counties,” the official noted. A 2019 study found that more than 308,000 Jewish adults lived in Philadelphia and the collar counties.

While the spokesperson acknowledged Trump is unlikely to win in most of the collar counties, the goal, he said, is to make inroads.

Picking off even a modest number of collar voters “could make a major difference statewide,” according to Chris Borick, a political science professor at Muhlenberg College and a pollster who heads its Institute of Public Opinion. He added: “There are no delusions Trump will win the non-Bucks Philly suburbs. But that’s not the game.”

Christian Nascimento, the chair of the Montgomery County GOP, said he saw opportunity through messaging on the economy and immigration for Trump and Vance to persuade more voters to their side. Nascimento argued that this wasn’t as essential as driving up turnout among existing supporters who might not be motivated to vote.

“The theory of the case is if you can drive up turnout in Montco, in places like Montco, that’s the key to winning the commonwealth,” he said. “But you don’t have to win it to win Pennsylvania.”

Trump’s and Vance’s events this week appeared aimed at doing just that. Trump’s town hall was packed with existing supporters. Ciarrocchi argued that simply showing up in the deep-blue county was a show of strength.

But Trump’s visit to the Philly suburbs might have also highlighted his vulnerabilities in the final weeks of the race as Democrats have been questioning the mental acuity of the 78-year-old Republican nominee.

After the former president spent about 30 minutes taking questions, he abandoned the town hall format after a pair of medical emergencies in the crowd. Instead of resuming questions, he swayed to music on stage as his adoring followers looked on — creating a spectacle panned by Democrats as evidence of cognitive decline, even as Republicans in the area applauded it.

Michelle Civitello, a 61-year-old retired pharmaceutical worker who attended the town hall, predicted that the suburbs will deliver more votes for Trump than people realize if he can keep hammering home an economic pitch.

“There’s a lot of closet Trumpers out there,” she said. “We’re here to come share support and be around others who feel the same way, because sometimes Montgomery County doesn’t make it easy for you to be a Trump supporter.”

Persuading Republicans

In an era where Democrats are losing support among working-class voters in Philadelphia, Harris needs to make up for those losses by driving up margins in the suburbs, where Democrats have steadily gained support for years.

At the Bucks County event, many Republicans or former Republicans seated near the Delaware River cheered as she pledged to be a president for all Americans in front of a white barn draped in a “Country Over Party” banner.

Brittany Prime, a cofounder of Women4US, a PAC aimed at persuading Republican women to vote for Harris, said Republican women, especially in the suburbs, could play a major role in swinging the state.

“Kamala Harris is saying we have a place in her campaign and there’s room for everyone, and I believe her,” Prime said.

Republicans have notched persistent registration gains in the area and GOP leaders insist they are seeing more outward support of Trump than they saw in 2020 or 2016.

In an effort to drive enthusiasm in the last several weeks, Harris’ campaign has been sending surrogates to the suburban counties. Those have included Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, first lady Jill Biden, and numerous celebrities like producer Shonda Rhimes and actress Jennifer Garner.

President Joe Biden made multiple visits to the Philly burbs this year, including a Delaware County speech the day after his State of the Union address, before withdrawing from the campaign in July. Harris has been a frequent visitor to Pennsylvania since becoming the nominee but had largely focused on the city and other parts of the state until this month.

While Harris herself has not been a fixture in the collar counties, a senior adviser for the campaign in Pennsylvania said that the region has been the focus of a “ton of surrogates working in 11 offices, coordinating doors being knocked on, people being called. We’ve had a ton of emphasis there — more presence than any previous presidential campaign.”

The adviser, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss campaign plans, said this was in “stark contrast” to the Trump campaign, which has “no real infrastructure in the suburbs.”

Montgomery County Commissioner Neil Makhija, a Democrat, argued there was plenty of room for the vice president to improve upon Biden’s vote totals by reaching Republican voters and those in communities that historically have been less engaged.

“There are so many places in this country where I think her having a touch where we have a moment where we can bring hundreds of thousands of people into the biggest venue we can find would be very important leading into Election Day,” he said. “It’s women, it’s people of color, it’s young people with families.”

But both campaigns run the risk of turning off voters in their fevered final-days pitch.

For Genevieve McCormack, 48, a Haverford attorney, candidate messaging, regardless of party, has been relentless.

“I’m a registered independent,” she said. “So that makes me prey to everybody.”

Winning voters in the collar counties apparently means annoying them, McCormack has concluded.

“I literally have gotten the same exact solicitation from both sides: ‘We need $100,’ as though it’s not a lot of money. Meanwhile, the Democrats want me to go to other neighborhoods and knock on doors. They write, ‘Here’s the calendar. When are you free?’ There’s no ‘please.’”

McCormack estimates she gets directly solicited via text at least 12 times a day. “I love our country,” she explained. “Our two greatest obligations are jury duty and voting. But this is all becoming exhausting.”

J. Wesley Leckrone, chairman of the political science department at Widener University, agreed.

“That’s why you’ll be seeing more of the candidates themselves in the collar counties,” he said. “Nobody watches these ads anymore.”

So Harris, Trump, and their running mates have to show up “just to cut through the static,” Leckrone said.

Graphics editor John Duchneskie contributed to this article.