City Council grills top health official on Philly Fighting COVID collapse and vaccine racial equity

Lawmakers questioned the health commissioner for more than four hours. But the hearing yielded few details about who advocated for the group or how it was vetted.

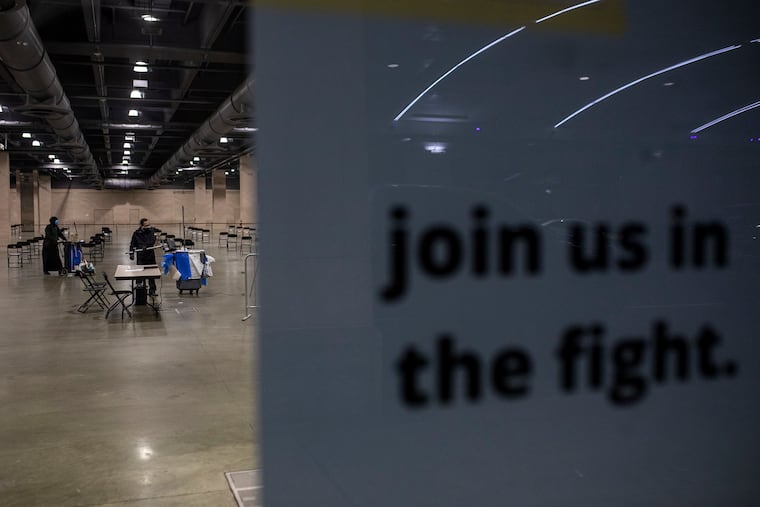

Philly Fighting COVID was only authorized to vaccinate home health aides at its Pennsylvania Convention Center site last month, but the city has no record of how many of the nearly 7,000 people vaccinated by the group actually fit that description, officials said Friday.

While a majority of home health workers in the city are people of color, the group — whose troubled partnership with Philadelphia drew embarrassing national headlines — failed to consistently record the racial breakdown of the people it vaccinated. Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said the organization appears to have vaccinated mostly white residents, based on the city’s distribution of second doses to them this week.

”The people who force their way to the front of the line and manage to get in often are people who are white,” Farley said. “I will fully acknowledge that problem.”

Those details were among the racial equity concerns raised during a City Council hearing Friday on the city’s vaccine distribution and former partnership with Philly Fighting COVID, a self-proclaimed group of “college kids” with whom the health department cut ties last week.

Council members have blamed Mayor Jim Kenney for failing to properly vet the organization. And they spent more than four hours questioning Farley and other top administration officials, who are scrambling to restore trust in the vaccination process. But the hearing yielded few new details about who advocated for the group, how it was vetted, and how the city can ensure such a debacle doesn’t happen again.

“It’s still important to me to find out who put their credibility on the line,” Councilmember Cherelle Parker said, suggesting that someone in an influential position advocated for Philly Fighting COVID. “I’m still pissed off about it right now.”

Farley said he wasn’t personally involved in conversations with Philly Fighting COVID, but ended the partnership after The Inquirer raised questions about the group’s policy allowing it to sell personal data through a for-profit arm. He declined to answer several questions from Council, saying the city’s inspector general has asked him not to interview his own staff to learn more until its own independent investigation is complete.

“I have many of the same questions that I can’t answer myself,” Farley responded at one point. “The rest of those questions are going to have to be answered when the inspector general report comes out.”

Farley said he delegated vaccine planning to Caroline Johnson, his deputy who resigned last week after records obtained by The Inquirer showed she gave the group an advantage in a city bidding process. He said the city has revamped its vaccine planning, and he participates in daily calls with other officials.

» READ MORE: The city says it can’t answer some questions about Philly Fighting COVID amid an investigation. That’s not true.

Philly Fighting COVID bid to receive city funding for vaccine distribution, but had no contract in place with the city for the Convention Center site. Like hospitals, pharmacies, and other organizations that receive vaccinations, the group signed an agreement with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Farley said the city checks medical licenses and inspects organizations for their ability to distribute vaccines, but doesn’t sign contracts with its 98 vaccine providers.

“Do you people Google folks?” Councilmember Isaiah Thomas asked. “I think there were a lot of signs that were right there in our face.”

Farley couldn’t say Friday whether the Department of Health did a Google or social media review of Philly Fighting COVID. Jim Engler, Kenney’s chief of staff, said the city would look into how other cities vet vaccine providers and how Philadelphia could improve its process.

Philly Fighting COVID’s inability to limit vaccines to eligible residents and ensure racial equity isn’t unique to that group, Farley said.

“Every provider that we’ve given vaccine to … those invitations have sometimes been forwarded to other people and people have come in and been vaccinated who were not in that target population” he said. “There are so many eager people out there.”

Farley acknowledged the city has fallen short on vaccinating people of color — only about 15% of vaccinations have gone to Black residents, who make up more than 40% of the city’s population — and said one reason was that people of color were “hesitant or less aggressive” about signing up.

Council members pushed back, raising concerns about racial equity and pointing to issues such as lack of internet access, language barriers for residents who don’t speak English, and the need to offer vaccination clinics in underserved neighborhoods. Council members also grilled Farley on the city’s choice to give more vaccine doses to Philly Fighting COVID than the Black Doctors COVID Consortium, a more qualified group that is also focused on racial equity.

Farley apologized to Ala Stanford, who leads the Black doctors group.

“I completely understand why Dr. Stanford would see it as disrespecting her,” he said, “and let me publicly apologize to her for that.”