An asteroid bigger than Philly’s City Hall will be ‘near’ Earth on Saturday, but not to worry

Should anything that size ever come truly near Earth — and there’s no sign that will occur this century — NASA is getting ready.

A massive asteroid will whiz past the Earth on Saturday, but hold any thoughts of disaster movies.

Though NASA defines the hunk of rock as a “near-Earth object,” the term near is relative. This asteroid will pass no closer than 2.6 million miles from us — 11 times the distance between here and the moon.

The oblong asteroid, dubbed 2004 UE, is attracting attention because of its size: more than 1,000 feet long and 460 feet wide, give or take. For perspective, that’s bigger than two Philadelphia City Halls, one piled on top of the other.

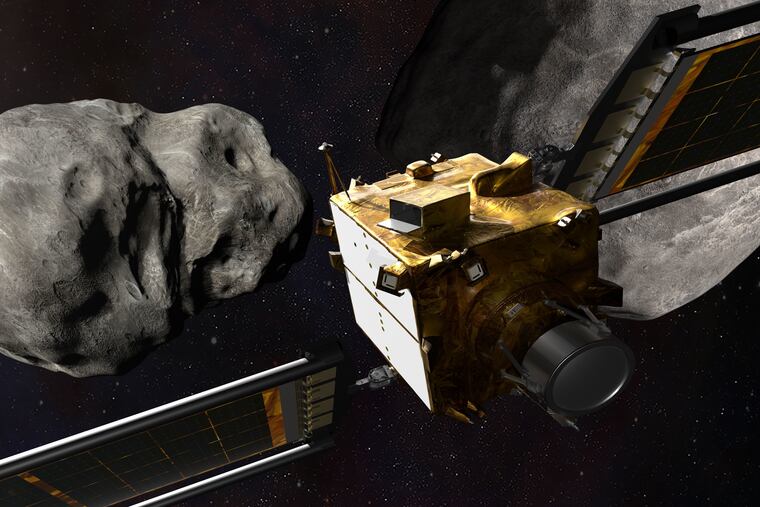

Should anything that size ever truly come near Earth — and there’s no sign that will occur this century — NASA is getting ready. Later this month, the agency is launching a spacecraft called DART, which will slam into an asteroid much farther out in space — a test of our ability to redirect such rocks should any approach us in the future.

In the meantime, the huge-but-harmless asteroid passing by on Saturday is a reminder that the cosmos is chock-full of debris. We spoke to Joey Neilsen, an astronomer and assistant professor of physics at Villanova University, to get the big picture.

What’s an asteroid?

Basically, a rock traveling through space, left over from the formation of the solar system. Scientists study them because they provide clues from long ago.

“They’re raw,” Neilsen said. “They’re remnants of the primordial solar system. They can give you hints of what it was like back then.”

The vast majority of asteroids are found in an asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Every so often, their orbits intersect with that of Earth.

What is a near-Earth object?

NASA defines an asteroid as being “near” the Earth not by its distance from the planet, but by how far it is from the sun.

If the object’s projected path comes within 120 million miles of the sun at any point, that is considered near enough to the Earth to warrant tracking with telescopes and sophisticated software. The trajectories of such objects are plotted years in advance.

“We know the orbits of these objects to really high precision,” Neilsen said. “We have a good sense of where they’re going to be at any given time.”

A small percentage of those objects are classified as “potentially hazardous” — at least 500 feet across, coming within 4.6 million miles of Earth. Even most of those, such as the big hunk of rock passing 2.6 million miles away on Saturday, pose little to no risk.

Can I see it?

Sorry. Saturday’s asteroid is too far away, and the light reflected off it too dim, to see with most telescopes.

Not even the Franklin Institute is holding a watch party.

What if one comes close?

Should an asteroid be projected to come anywhere near Earth, the idea is to nudge it into a different direction well in advance.

That’s the goal of DART, a spacecraft developed for NASA by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md.

The car-size craft is scheduled for launch later in November. Ten months later, in September 2022, it will slam into an asteroid called Dimorphos, traveling at a speed of 4 miles per second.

How often are we at risk?

More than 100 tons of dust and sand-size particles hit the Earth every day with no consequence, NASA says.

“We’re constantly being bombarded,” Neilsen said.

About once a year, a car-size asteroid enters the Earth’s atmosphere, but burns up before reaching the surface. It makes for an impressive fireball, but again, no threat.

An object large enough to survive that fiery descent intact — called a meteorite — is much rarer. One the size of a football field hits the Earth every 2,000 years, on average, NASA says.

A meteorite large enough to threaten civilization hits the planet on even rarer occasions, generally with millions of years between impacts. The most famous example is the one that wiped out most dinosaurs, 66 million years ago.