Delaware is considering offshore wind as feds approve 100,000 acres off the state’s coast

Both New Jersey and Maryland are already moving ahead with offshore wind projects.

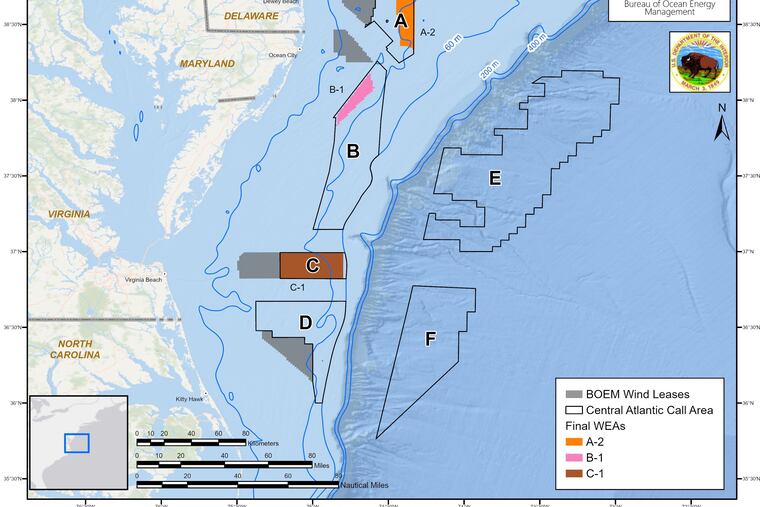

The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) announced this week the creation of more than 100,000 acres off the coast of Delaware that could potentially be used for offshore wind. It would be an opportunity for the state to tap a renewable energy source most other states along the East Coast have already embraced.

The action comes after Delaware recently took its own small step toward exploring what that form of renewable energy might entail, but the state still lags years behind neighboring states, such as Maryland and New Jersey, in planning for offshore wind.

The Delaware offshore wind area encompasses 101,767 acres that lie 26.4 nautical miles (30 miles) from Delaware Bay at an average depth of 121 feet. The area is prime territory for surf clam and scallop fishing. According to a BOEM map, the area is off the midpoint of the bay, with Cape May just to the north.

What are the wind areas?

The BOEM announced the new wind energy areas Monday for locations within the outer continental shelf off Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. If all of the areas were developed for offshore wind, they could support between 4 and 8 gigawatts of energy production, enough to power millions of homes.

The announcement of the areas within federal waters is meant to facilitate the development of wind farms. But they’re not automatically authorized. BOEM would still need to bid for leases and conduct environmental reviews.

And Delaware would have to create policies, choose a developer, and ensure any projects get connected to an electrical grid to bring power onshore.

The BOEM announcement comes as part of President Joe Biden’s goal to deploy 30 gigawatts of offshore wind energy capacity by 2030. The BOEM is currently accepting public comments on the leases and has posted related documents online.

It takes years to launch a wind project

The first Delaware wind farm, if it gets state approval, is likely years away. Offshore wind gained some momentum in 2017 when Gov. John Carney, a Democrat, established a group to explore the idea as part of his administration’s goal of achieving 40% renewable energy by 2035. The group sent a report to the governor in 2018. At the time, it was believed offshore wind would be too expensive.

Another report was generated under guidance of the University of Delaware in 2022. That report led by Willett Kempton, a University of Delaware professor, concluded, however, that prices had dropped substantially and laid out a potential process to move forward.

In June, Delaware State Sen. Stephanie Hansen, a Democrat and chair of the Senate Environment, Energy & Transportation Committee, introduced a bill that directs the state’s Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) to look into wind and restart the process of examining whether wind is feasible. The bill passed the Senate and House and awaits Gov. John Carney’s signature.

The bill directs DNREC to study the matter and report back to the governor and assembly by December with a process for how the state could start an offshore wind project.

”This is a bill that really recognizes that we need to take a look a look at offshore wind and whether or not this is something that we should be involved in,” Hansen said during the June session when the bill was introduced.

Hansen said it was important to know how offshore wind “might affect us as a state, what the cost could be going forward.”

The legislation notes that Delaware has the lowest average elevation of any state and “is particularly vulnerable to related climate change impacts like sea level rise, flooding, saltwater intrusion into drinking water, erosion, wetland loss, beach loss, and extreme storm events.”

Hansen was asked if the bill would require more money, and she said it would not.

Shawn Garvin, head of DNREC, said the study asks for a lot of information that his agency has already been exploring the past several years.

“This bill codifies a lot of work that we’re already doing,” Garvin said during the same session. “We’ve got a lot of data, but there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done.”

Almost all members of the public who spoke supported the bill and urged officials to act quickly.

Mary Douglas, a retired environmental lawyer who worked for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, said there are 18 offshore wind projects proposed and in various stages off the Atlantic Coast.

“All states from Massachusetts to North Carolina, except for Delaware, have initiated offshore wind projects,” Douglas said.

Potential opposition

Indeed, New Jersey has already approved multiple projects through its Board of Public Utilities. Recently, the U.S. Department of the Interior approved construction and operation of the first project, Ocean Wind 1, which would be located 13 nautical miles (15 miles) southeast of Atlantic City. The project would have capacity to produce 1,100 megawatts of energy, or enough to power 380,000 homes. Orsted, the company building the project, is expected to start laying cable and building onshore substations this year, with construction of the wind farms to follow in the second quarter of 2024.

And Maryland has approved multiple projects totaling 2,023 megawatts of offshore wind capacity expected to power 600,000 homes.

Both New Jersey and Maryland are involved in building facilities that support offshore wind.

Though Hansen’s bill easily passed both the House and Senate, there have been signs of brewing opposition similar to what New Jersey has faced. Some residents and groups in New Jersey have objected to having views impeded by skyscaper-high turbines, though distant. And they have suggested links between whale deaths and surveying vessels used for offshore wind, though scientists have largely dismissed any such connection.

Delaware State Sen. Bryant Richardson, a Republican, was the lone dissent on the vote for the bill.

“I will not be voting for this bill for a number of reasons,” Richardson said. “One, I’m very much concerned about the effect that this will have on our planet, on the oceans, on the birds, and on the aquatic life.”

Clean Ocean Action, a New Jersey-based environmental advocacy nonprofit, has already sent a public comment regarding BOEM’s creation of the Central Atlantic wind areas that include Delaware. The group held a news conference earlier this year in New Jersey after several whale deaths.

“The impacts of this large-scale, industrial use of the ocean are largely unknown and will likely cause irreversible harm to the marine environment and marine life,” Clean Ocean Action told the BOEM. “Many important questions remain unanswered, including critical issues of environmental concern, which puts the ocean and marine life at risk if more and more wind turbines are slated for offshore waters.”