These Philly award-winners tackle problems from inside the brain to outer space

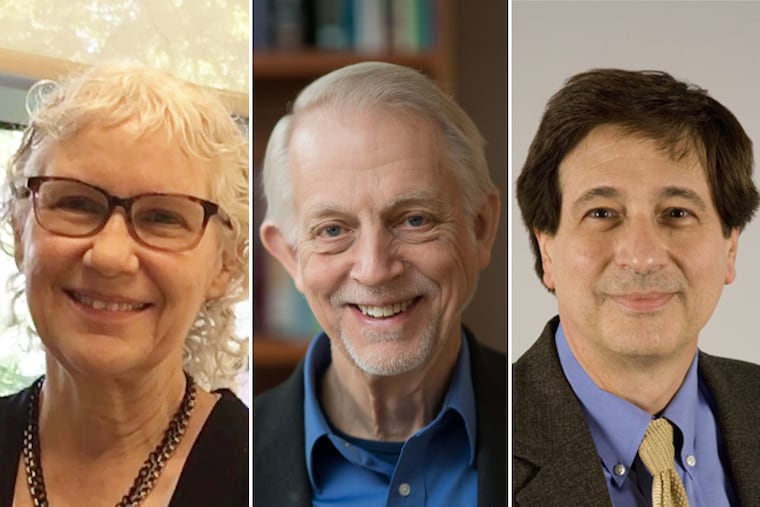

The 2022 Scott Awards are going to scientists at Penn, the Monell Chemical Senses Center, and Doylestown-based Catemer Inc.

Nancy Bonini studies Parkinson’s and other human brain diseases by probing the genes of a lab animal smaller than the head of a pin: the fruit fly.

Gary Beauchamp made fundamental discoveries about the human senses of taste and smell, showing how we can be weaned from excess salt and maybe, in an upcoming study, from sugar.

Barry Arkles has used chemistry to improve such diverse products as soft contact lenses and the tiles that shielded the Space Shuttle.

The three Philadelphia-area researchers were honored Thursday with John Scott Awards, prizes given annually by a city-affiliated group of citizen trustees to recognize achievement in the sciences.

First bestowed in 1822, the prize was endowed by Scott, a chemist and pharmacist from Scotland, in honor of Benjamin Franklin. Seventeen recipients also have won a Nobel Prize, including K. Barry Sharpless, who won the first of his two chemistry Nobels in 2001, the same year as his Scott Award, followed by the second this year.

Bonini, a University of Pennsylvania biology professor; Beauchamp, the president emeritus of the Monell Chemical Senses Center; and Arkles, the co-founder of a series of tech startups, each received a medal and $10,000 in a ceremony at the American Philosophical Society.

The awards are given by the Board of Directors of City Trusts, a group that manages dozens of charitable trusts for which the city of Philadelphia is a trustee. The winners are chosen based on recommendations from a panel of scientists, which includes representatives from Penn and Temple and Drexel universities.

Here’s how this year’s winners made their mark.

Gary Beauchamp

Decades ago, Beauchamp demonstrated that people who were restricted to a low-salt diet could reduce their innate craving for salty foods. The research set the stage for government and policy groups to recommend reducing salt consumption.

Now, in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, he’s setting his sights on sugar.

The plan is to feed volunteers a low-sugar diet for more than three months, measuring whether that diminishes their natural sweet tooth. Their results will be compared with outcomes for two other groups: one on a normal diet, and one for which sugar is replaced with artificial sweeteners.

If the low-sugar diet is effective, it could inform efforts to combat obesity and Type 2 diabetes. But preliminary evidence suggests sugar cravings may be harder to suppress than the urge for salty foods, said Beauchamp, who was Monell’s director from 1990 to 2014.

“We’re built to like sweet things,” he said.

In more than five decades at Monell, Beauchamp has tackled what he describes as an “eclectic” range of other projects. Among them: studying how bodily odors may be helpful in the early diagnosis of disease, and how a compound in extra-virgin olive oil acts as an anti-inflammatory agent.

Nancy Bonini

When Bonini came to Penn in 1994, fruit flies had long been a staple of biology research, as the insects are easy to raise and, despite their small size, share a substantial degree of genetic kinship with humans. But Bonini was among the first to use the flies to tackle diseases of the human brain, using genetic engineering to induce similar symptoms in the insects.

Her focus is neurodegenerative diseases — those marked by abnormal accumulations of proteins, such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), nicknamed Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Among her first successes, working with colleagues at Penn’s medical school, was creating flies with one such disease that impairs muscular control, called spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. She later made flies with symptoms of Parkinson’s, then discovered a variety of genetic tweaks that could slow down the disease’s progression.

Drawing on that research, Bonini and her colleagues identified a drug that protects flies against Parkinson’s by ramping up the stress response in their brains.

That drug is unlikely to be practical for humans, as it would be difficult to deliver in sufficient amounts. But the research illustrates how that same genetic pathway is likely to be relevant in the human version of the disease, she said. Other drugs may help in humans if directed at the same target.

“The fly is a powerful addition to our collective scientific tool kit,” she said, “to learn about and provide the foundation for treatment approaches.”

Barry Arkles

A Temple-trained Ph.D. biochemist, Arkles has built a career out of chemical compounds that contain silicon, the second-most abundant element in the earth’s crust.

It started with a summer job in the late 1960s at an engineering plastics firm, where he helped to develop materials used in Kodak slide projectors and Polaroid cameras.

He went on to found three research companies, in one case developing silicon-based compounds that are now widely used in soft contact lenses, thereby allowing more oxygen flow to the cornea.

Arkles later worked with NASA after the 1986 explosion of the space shuttle Challenger, which lost some of its surface tiles because they had absorbed moisture.

Once again, his answer was silicon, due to its water-repellent properties. Arkles developed a silicon-based coating that not only protected tiles from moisture on subsequent shuttle missions, it also helped the tiles withstand the heat of reentering the earth’s atmosphere.

Elected in 2021 to the National Academy of Engineering, Arkles is now applying silicon chemistry to human disease.

At Doylestown-based Catemer Inc., he is exploring the use of silicon-based molecules to treat diseases called channelopathies, including certain types of irregular heart rhythms. These conditions are so named because they involve deficiencies in the channels through which chemical ions move across cell membranes.

“This is a sort of a long shot, but at this point in my career,” he said, “I think I’ve got maybe a little different way of looking at it.”