How the Sixers nearly drafted Bill Walton 50 years ago, and why he rejected their offer

They had the No. 1 overall pick in the 1973 NBA Draft. But the UCLA great was only a junior.

It wouldn’t be correct to call it a secret meeting, because the six men who gathered at the Park Chase Hotel in St. Louis on March 26, 1973, just a couple of hours after perhaps the greatest single-game performance in the history of the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, weren’t hiding anything. The meeting was part of a negotiation, each side resolute in its aims and actions, and no one at the table was less inclined to change his mind than the 20-year-old kid, his 6-foot-11 frame topped by a mop of red curls, who wanted peace, love, and no parts of the NBA yet.

On one side were the three men in charge of the 76ers: owner Irv Kosloff, general manager Don DeJardin, and coach Kevin Loughery. On the other were two businessmen — UCLA boosters and power brokers Sam Gilbert and Ralph Shapiro — and the athlete they were advising: Bill Walton. Earlier that night, in the Bruins’ 87-66 victory over Memphis State in the national title game, Walton had scored 44 points, making 21 of his 22 shots from the field and cementing himself, though he was just a junior, as the best player in the country. Kosloff, DeJardin, and Loughery had been inside St. Louis Arena to bear witness to Walton’s dominance. The Sixers had just finished the worst season that any NBA team had ever experienced, going 9-73, but they had won a coin flip to acquire the No. 1 pick in the draft. Walton was the obvious choice … if they could persuade him to skip his last year at UCLA.

One writer later described the summit as “a very informal, getting-to-know-you kind of thing.” The mood was amicable, but Walton never showed his hand, never did or said anything to indicate that he had moved off his insistence that under no circumstances would he leave college early. The next day, after returning to Philadelphia, DeJardin wrote Gilbert a letter, a copy of which, more than 50 years later, was obtained by The Inquirer.

“We found Bill to be exactly as you had described him — an eloquent, open, and completely honest young man whose sincerity is obvious,” DeJardin wrote. “In fact, our major source of discouragement came as a result of our inability to present our entire proposal.”

So, for the next three pages of the letter, DeJardin did. He laid out in full the Sixers’ offer to Walton. It would turn out to be their last, best chance to acquire a player who at the time was regarded as transformative. It would also turn out to be DeJardin’s last, best chance to save his job.

Men of conviction and contradictions

Bill Walton began by apologizing. We were supposed to talk by phone at 10 a.m. West Coast time one day last week, but he didn’t call until 10:37. “I am so embarrassed and ashamed that I am 37 minutes late,” he said. “My day has gotten away from me.”

All his days have been busier lately. Earlier this month, ESPN premiered a four-part documentary on Walton as part of its 30 for 30 series, thrusting him back to the forefront of sports fans’ consciousness, not that he ever really went away. He is 70 now, and his entire life has been an amalgam of competitiveness and contradictions, courtliness and counterculture.

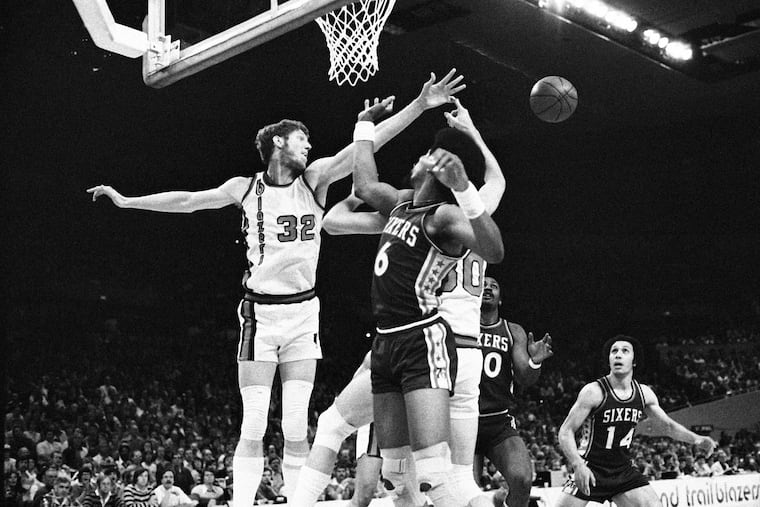

He was a Deadhead who believed in discipline on the basketball court. He was a purveyor of both leftism and the Pyramid of Success, counting among his closest mentors John Wooden and the radical activist Jack Scott. He overcame a stutter to spend more than 30 years in broadcasting, delivering monologues and making pronouncements that at times seem too exaggerated to be sincere. He won two NCAA championships and two NBA championships — one of them with the Portland Trail Blazers in 1977, of course, in six games over the Sixers — yet to this day considers UCLA’s 1974 Final Four loss to North Carolina State, in his penultimate college game, to be so profound a failure that it overshadows those triumphs. The man has always contained multitudes.

Fifty years after Walton turned them down, the Sixers enter Thursday night’s draft without any picks at all. A cynic would suggest that they’re better off not having one, for it eliminates the possibility that they will extend their tradition of bad decisions, bad timing, and bad luck. No drafting then trading Mikal Bridges. No handing the Celtics a first-round pick just to get Markelle Fultz. No preferring Larry Hughes to Paul Pierce. No finishing second in the lottery the year that Tim Duncan is available. No breaking down the franchise for Jeff Ruland, Roy Hinson, and Cliff Robinson.

» READ MORE: Sixers enter ‘Wemby Draft’ without picks, mirroring position in historic 2003 draft 20 years ago

Their inability to draft Walton counts among the oldest of those might-have-beens — and one of the most fascinating to view through the prism of the passage of time. Sam Hinkie couldn’t have planned it better: The Sixers were the NBA’s worst team in 1972-73 and again in 1973-74, when they went 25-57 and Walton, the kind of talent for which a team considers tanking, had no eligibility left at UCLA. But in neither year did they have the opportunity to select him. They took Doug Collins, out of Illinois State, with the ‘73 draft’s first pick and, after Portland won another coin flip and picked Walton, Providence’s Marvin Barnes with the ‘74 draft’s second pick. And even if they’d had the opportunity, it wouldn’t have mattered.

“I was not interested in going to Philadelphia,” said Walton, a native of La Mesa, Calif., who added that if the Sixers had secured the No. 1 pick in 1974 and selected him, he would have chosen to play in the ABA. “I loved California. I loved UCLA. I loved the team I was on. I never thought about leaving. I had zero interest in leaving UCLA early. Zero.”

The Sixers were undeterred, though, and DeJardin was, in his background and profile, the perfect adversary in the franchise’s battle of wills with a player whose fondness for headbands and strident opposition to Richard Nixon and the Vietnam War unnerved the establishment. Hired by the Sixers in August 1970, DeJardin was an alumnus of West Point, where he captained the basketball team, and a lieutenant in the Army.

“He was not a weak person,” DeJardin’s son Brad said in a phone interview. “He absolutely would have had a difference of opinion with Walton, but Walton was a very cerebral guy, and I think my dad would have gotten along with him.”

More, DeJardin understood that a center who had averaged 20.8 points and 16.2 rebounds over his first 60 games, all victories, for Wooden’s dynastic program was worth exhausting every possible option and enticement. To be eligible for the ‘73 draft, Walton had to declare by March 30, just four days after the UCLA-Memphis State game, that he was entering the pool of available players, and the NCAA had to designate him a hardship case, a player whose economic and/or family circumstances made turning pro an imperative for him. Both qualifications were long shots, but DeJardin, in his letter to Gilbert, outlined the steps Walton would have to take to fulfill them. Then, he got down to business.

The Sixers offered Walton a seven-year contract with an annual salary of $360,000, for a sum of $2.52 million. By comparison, three years later, they would sign Julius Erving to a six-year contract worth $3 million.

If Walton was “unable to perform … for any season,” he would be entitled to receive his salary “for two years beyond his becoming disabled or unfit” — a helpful clause to a player who, because of various injuries, most of them to his feet and legs, would miss four full seasons and play more than 67 games just once over his 14 years in the NBA.

The Sixers would pay for Walton to complete his undergraduate degree at UCLA — tuition, books, fees, the works. They would provide him with a car, at a cost of no more than $10,000, and an apartment in the Philadelphia area, for no more than $400 a month in rent.

During the first year of the agreement, the Sixers would guarantee Walton “a minimum remuneration of $15,000 from WCAU (CBS)-TV for training in the television broadcasting field.”

Walton doesn’t remember reviewing the proposal himself. If anything, he said, he was so uninterested in playing for the Sixers and so naïve about financial matters that he probably ignored Gilbert and never bothered to read DeJardin’s letter.

“I’m sure that I was Sam’s worst nightmare,” he said. “When my contract with Portland was being negotiated, I told him, ‘The only thing I care about is that I don’t want anybody to be able to tell me when I have to cut my hair, when I have to shave, and what clothes I want to wear.’ So he looked at me and said, ‘OK … ?’

“I was unprepared. I was incapable of playing in the game of life. That’s the way I was. That’s the way I am. And that’s the way it played out.”

The hope for something dramatic

Despite the Sixers’ awful 1972-73 season, DeJardin was still their GM on April 24, 1973, when, with that precious No. 1 pick, they took Collins. After his contract with the franchise expired, DeJardin, who died in 2011 at age 75, continued to work for the Sixers for another six weeks, without a formal agreement, before Kosloff officially fired him that September. He became a player agent, never working in another NBA front office again.

“I delayed the decision,” Kosloff told The Inquirer, “in the hope that, between the end of last season and this, we could sign Walton or do something dramatic.”

Had Walton been open to coming to the Sixers, how different might have things been for him and the franchise? With Walton already in the fold, would the Sixers have felt the need to pursue Erving and pay any price for him in 1976? Would Walton have thrived and felt as comfortable here as he did in lower-key Portland? His politics and his propensity for injury would have made things challenging for him, to be sure. “The Philadelphia press,” Brad DeJardin said, “would have absolutely crushed Walton.”

» READ MORE: Looking for a Sixers draft-night trade? Why that might be more difficult to pull off this year.

True to form, when Walton missed his first seven shots and managed just 10 points and nine rebounds in a 105-89 loss to the Sixers on Nov. 8, 1974, Daily News beat writer Phil Jasner drew blood with his lede in the next morning’s newspaper: “A year ago, Bill Walton said he would not play pro basketball in Philadelphia. He came to the Spectrum last night and kept his promise.”

Yes, all things considered, it was probably better for Bill Walton to have stood firm. In the Pacific Northwest and on the California coast, the blades were never so sharp.

» READ MORE: Former Eagles punter Max Runager died with CTE. His son wants the NFL and everyone else to notice.