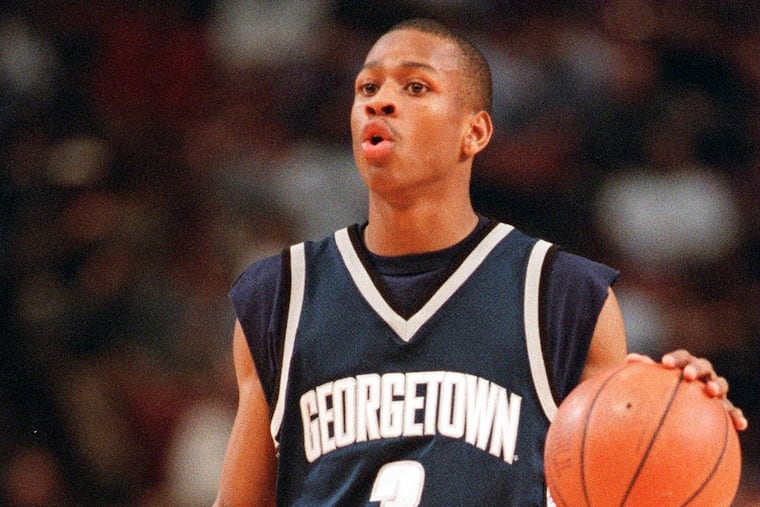

‘You have to show me’: Meet the Georgetown walk-on who taught Allen Iverson his killer crossover

It’s been 25 years since Iverson used his famed move on Michael Jordan and revolutionized basketball. Dean Berry, who taught Iverson during their lone season together, explains the process.

Dean Berry was the last kid added to the AAU team, a late substitute when another player on the New York squad got sick before a big tournament in Washington.

He had never played in an event like this — a showcase that included top college recruits and future NBA lottery picks — so it was easy to understand why Berry was a bit unsettled as he boarded the double-deck bus taking players across town during a break in the action.

But before Berry joined his teammates on the second level, a player from another team stopped him. It was Allen Iverson, the 15-year-old dynamo who stuck it to Berry’s squad a day before.

“Man,” Iverson said. “Your crossover is really good. Just keep doing it.”

Iverson would soon revolutionize basketball with his dribbling, beginning most notably with his crossover 25 years ago that shook Michael Jordan. But Iverson had yet to learn the move that would define his career.

And it was Berry — then a nervous teenager from Brooklyn — who would be the one to teach him.

“The way he said that to me, it was just so inspiring that I never forgot that,” Berry said. “He inspired me and changed my life. I get the chills just talking about it.”

» READ MORE: 76ers tried solving their backup center dilemma by bringing Wilt Chamberlain out of retirement

Berry honed his game on Sundays at Brooklyn’s Dean Playground, playing early-morning pickup games with some of New York’s finest players. Berry was short — 5-foot-11¾. “With shoes, I’m probably 6-foot,” he said — so he needed to find a way to create space against players like Conrad McRae, a 6-10 McDonald’s All American who played at Syracuse.

“I’m not the tallest, I’m not the fastest, I’m not the quickest,” Berry said. “I had to have something.”

He found that “something” by borrowing NBA highlight tapes from the older players he played with at the playground and studying the moves of players like John Stockton, Tim Hardaway, Kenny Anderson, and Isiah Thomas. Berry rewound the VCR tapes over and over, analyzing how those small guards used their dribbling to separate just enough from defenders to get shots off against taller players.

“When you put those four guys together — and some more guys, of course — you get something rather unique,” Berry said. “I think that’s where that whole crossover thing came from, just me having to create more space.”

Berry swept the ball across his body from his left hand to his right hand, moving the ball in the opposite direction of where the defender’s momentum was carrying him. He didn’t invent the crossover, but he added his own wrinkle to it and it helped him get to that AAU tournament in Washington.

The New York team, Berry said, was “the team to beat” as it was led by top college recruits Zendon Hamilton and Jamal Robinson. That didn’t matter to Iverson, who started the game with a quick steal and a fast-break dunk over one of the New York players.

“This guy was like my size,” Berry said. “He just played with this relentless energy and passion that I had never in my life seen before. Allen was the best player I had ever played against in my life.”

The New Yorkers were down double-digits by the time Berry got off the bench, but he still tried firing up his squad after he made a basket.

“I’m from New York, so I have a little edge on me,” Berry said. “I remember saying to my guys — and Allen was right there when I said it — I said, ‘Let’s get this win. Let’s show these guys who we are.’ He said to me, and I’ll never forget this, ‘I think you’re a little too late for that.’ I’ll never forget that.”

A day later, Berry was boarding that bus when Iverson stopped him.

“That stuck with me my whole entire life,” Berry said.

Iverson arrived at Georgetown in August of 1994, seven months after being released from prison by the governor of Virginia. His four-month stint in prison on charges stemming from a bowling alley brawl cost Iverson his senior high school season.

So the Kenner League summer matchup at Georgetown’s McDonough Gym was Iverson’s first organized game in a year. And one of his teammates that night on “The Tombs” was Berry, who was entering his senior year in high school at a boarding school just outside of Washington.

“I was the first one to throw him a lob,” Berry said. “I was the first one to get his assist.”

Berry hung around campus in the summer and dreamed of playing for the Hoyas, a dream that grew deeper after Iverson came to school.

“I wanted to be around someone who believed in me when I didn’t know I had the skills,” Berry said.

A year later, Berry made John Thompson’s Georgetown squad as a walk-on. He practiced against Iverson every day, using the same crossover dribble that grabbed Iverson’s attention years earlier at that AAU tournament.

Berry’s jersey did not have his last name on the back since he walked-on, leading him to chirp to his teammates that “I don’t have a name on my jersey but you still can’t guard me.”

Iverson had his own crossover — a through-the-legs dribble he copied in high school from Hardaway — but he needed to know how Berry did his. Iverson was the star player headed to the NBA. He had to humble himself before asking a walk-on for help.

“I would always get him with the move. It was the one move that you knew was coming but you just couldn’t stop it. So I would keep doing it over and over,” Berry said. “He pulled me over one day and said, ‘Man, you have to show me this ... ’”

Berry showed him the dribble and then watched Iverson work tirelessly to master it.

“We played all the time and he would try and do it all the time,” Berry said. “It got to the point where he just felt so comfortable doing it that it manifested itself into his game so he would just do it whenever the opportunity came up. It’s a matter of repetition and he did it so much. That soundbite where he’s talking about ‘Practice, practice, practice’ frustrates me so much because people don’t understand how hard this guy worked.”

Berry played four seasons at Georgetown, one of which was with Iverson before he left school to join the 76ers as the No. 1 pick in the 1996 draft. That one season was enough for Berry to call Iverson his “favorite player.”

When Berry remembers that one year, he recalls Iverson being taken out of practice by Thompson because he was working so hard that he embarrassed the rest of the team. Berry remembers the way Iverson didn’t seem to get tired when Thompson ordered the team to run line drills and he’ll never forget the time the 6-foot Iverson tried to dunk over Colgate’s 6-10 Adonal Foyle in the season opener of Berry’s freshman year.

“He dislocated his elbow and he didn’t want to come out,” Berry said. “He had a dislocated shoulder, a dislocated wrist, and he still went out there and played. He worked so hard every time he was on that court.”

Berry was still at Georgetown when Iverson’s 76ers hosted Jordan’s Bulls in March of 1997.

Iverson’s spectacular rookie season was winding down and it would be best remembered by this sequence. Iverson got the ball at the top of the key and heard Bulls coach Phil Jackson yell Jordan’s name, instructing Jordan to defend the rookie. This was Iverson’s chance to test himself against the player he grew up admiring.

Iverson moved the ball from his left to right hand — “a little cross,” he would later say — to see how Jordan reacted. Berry, watching on TV, knew what was coming as soon as he saw Jordan shuffle his feet.

Iverson allowed Jordan to set himself and then hit him with another crossover, the move Berry taught him. Jordan went right and Iverson went the other way, hitting a jumper over Jordan’s outstretched hand. He used the crossover to create just enough space— the same way Berry did on Sunday mornings at the playground.

“I’ve done it so much that I don’t even think about it,” Berry said of how it feels when a defender bites on a crossover. “Sometimes, in high school, I would do it and not even realize that a guy fell or went flying out of bounds. It’s just a part of the game, but when you look back at the film, you’re like, ‘I just did that.’ That’s the feeling. When you’re in the game, you’re just trying to get somewhere. You’re not trying to put on a show. You’re trying to get somewhere and it just happens.”

The crossover became a staple of Iverson’s game. He used it so much that it’s hard to imagine there was a time he didn’t know how to pull it off. Iverson changed the NBA in his 14 seasons, helping usher the league into the post-Jordan era and cementing himself as one of the most popular players in NBA history.

Iverson reached the Hall of Fame in 2016 and Berry was watching his old teammate’s induction speech when Iverson began to list Georgetown players who inspired him. Iverson rattled off the greats like Alonzo Mourning, Dikembe Mutombo, and Patrick Ewing.

“And Dean Berry,” Iverson said. “Maybe I wouldn’t be standing here if it wasn’t for Dean Berry teaching me the crossover. A walk-on. The man didn’t even have a name on the back of his jersey. But at practice, he used to hit me with it so much that I just put my pride aside and said, ‘OK. You have to teach me that move.’ I stayed after practice with him every day to learn that move. All these years later, Allen Iverson is known for the crossover.”

» READ MORE: Sixers’ Joel Embiid just passed a major milestone and nobody seemed to notice | David Murphy

Iverson changed Berry’s life when he stopped him on the bus and Berry changed Iverson’s life — and perhaps the history of the NBA — when he taught him the move that Iverson could not stop. When Iverson reached the Hall of Fame, he remembered the kid from Brooklyn who was trying to find his way.

“I wasn’t expecting that,” said Berry, who lives in Florida and coaches youth basketball. “But he’s such a genuine person that when I thought about it, I wasn’t shocked. This guy is going to mention the people he values and I really felt special that he did that.”