At last, the Hall of Fame gets defensive and welcomes Sixers great Bobby Jones

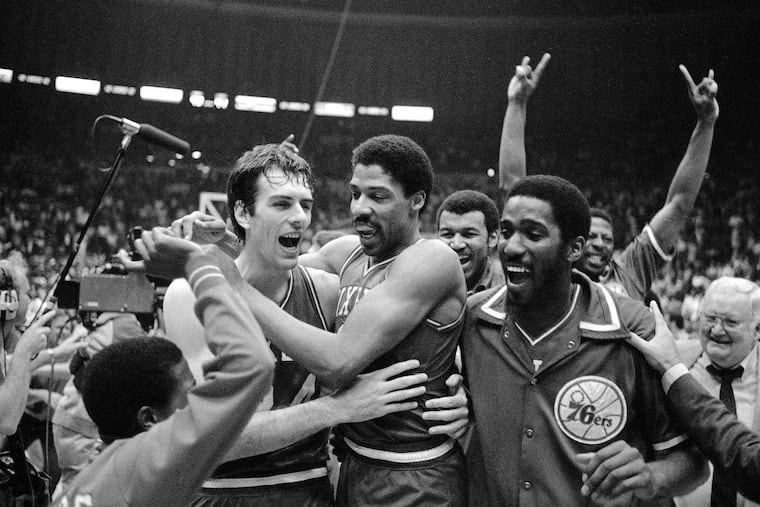

Jones, now 67, drifted reluctantly into basketball and left it a star. This Friday, in Springfield, Mass., he'll become the fourth member of the 1983 Sixers to be inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

CHARLOTTE, N.C. – Phil’s Deli was empty, but Bobby Jones instinctively headed for a booth in a distant corner. He slid his 6 feet, 9 inches behind the table and for 90 minutes, ordering only a glass of water, practiced the unnatural art of talking about himself.

The unpretentious former 76er, once a sparrow in a peacock-dominated NBA, appears as you’d imagine he would at 67. He’s bald, gaunt, still lean as a Carolina pine and socially awkward.

Jones and his wife live here in the city where he grew up, not far from grandchildren, close to the high school where despite big feet, asthma, epilepsy, a heart ailment and a distaste for sports, he morphed into a basketball star.

“The Lord has a sense of humor,” said Jones, a devout Christian. “He probably thought, 'Let’s see if I can make this spastic kid into a ballplayer.’ ”

It happened. He drifted reluctantly into basketball, won a state championship at South Mecklenburg High, starred at North Carolina, played in the 1972 Olympics, made five ABA and NBA All-Star appearances and eight straight all-NBA defensive first teams. In Philadelphia, playing with fascinating teammates such as Julius Erving, Charles Barkley, and Darryl Dawkins, he was as popular as he was invaluable -- blocking shots, diving for balls, corralling high-scorers.

This Friday in Springfield, Mass., Jones, as usual, will seem misplaced. The gangly forward with the unruly hair who averaged a pedestrian 12 points and six rebounds will be inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame, the fourth member of the champion 1983 Sixers so honored.

For Jones, the interviews and ceremonies, the spotlight and red carpet will trigger pride and joy, but also a social dread.

“I don’t like the limelight,” Jones said. “I don’t like crowds. It was a blessing that I was on teams with great players like David Thompson and Julius [Erving]. I could be effective, do what I wanted, and then fly out while everybody was taking their pictures.”

It’s been 33 years since he flew from the NBA, retreating to a Charlotte home whose backyard he has converted into a dream-worthy playground for seven grandchildren. He has seldom emerged.

In the late 1980s, the fledgling Charlotte Hornets wanted him as their first general manager. Jones said no when told he’d have to put job over family. Since then, he has worked briefly with a Charlotte ministry, done public speaking, and coached at nearby Christian schools where one of his players was Steph Curry.

“One night when Steph was in middle school, we got beat to death,” he recalled. “He didn’t hang his head. After practice ended, he stayed and worked. I thought, ‘This kid wants it.’ ”

These days Jones dotes on his family, gardens, and studies the Bible, which he has read through in each of the last 30 years.

Path to Springfield

Last April, while driving, he learned of his Hall selection, something Erving had predicted for his friend. Over the previous 30 years, he’d been nominated often but fallen short. It might not have happened this time either if the Hall hadn’t recently shifted its selection criteria to include more emphasis on defense.

“Jerry Colangelo [chairman of the Hall’s board] said the committee made that a conscious decision. That put me and several others much higher on the list,” said Jones, a first-team defender for 10 straight pro seasons. “Defense wins. You spend half the time doing it, so it should have importance.”

Jones will be a Hall rarity -- a defensive specialist and complementary player who for many Philadelphia seasons was a sixth man. But while he never averaged more than 15.1 points, few shooters were as efficient.

After setting a single-season Atlantic Coast Conference shooting-percentage record (66.8) as a Carolina sophomore, Jones three times led his pro league in that category. Through 12 ABA and NBA seasons, he made 56 percent of his shots.

“I learned I didn’t need the ball to succeed,” he said. “For a lot of guys, how many shots and points you get, that’s important. Every year I’d set a goal to get 100 blocked shots, 100 steals. Those stats don’t take away from anybody else.”

76ers coach Billy Cunningham, he recalled, had only one play for him – a foul-line screen meant to get him a 15-footer. He rarely shot – or hit – from farther out. Jones took 17 career three-pointers, made none.

“I wasn’t creative,” Jones said. “It’s not in my mindset to stand out or be flashy. I had deficiencies, but from the free-throw area in, I was a pretty good shooter. Most of the threes were end-of-quarter heaves. I remember taking one. It wasn’t even close.”

That lone shortcoming, offset by his ability to score elsewhere, to defend, and make teammates better has led some to compare Jones to current 76er Ben Simmons.

“I enjoy watching Simmons,” Jones said. “He’s intense, very strong, and certainly a good defender. But sometimes I wonder if there’s a fear of failure in shooting. If there is, that’s got to be overcome … you’re hurting the team.”

‘Like homework’

Born to a Goodyear executive, Jones was a shy, introverted youngster who rushed home from school to watch soap operas. Tall but awkward, he spurned basketball even though his father had played on an NCAA-runner-up at Oklahoma and his older brother would earn a hoops scholarship there.

If his father hadn’t assigned him daily drills, he might never have picked up a basketball.

“It was like homework, something I had to do, not something I enjoyed” Jones recalled. “He’d say, ‘Do 10 hook shots with either hand, 25 tips with either hand, 25 free throws.’ I’d come home from school and watch my shows. But during commercials, I’d run outside, get done what I could, then run back in to watch the rest of my shows. I had no desire to be a ballplayer.”

He discovered high-jumping at South Mecklenberg and blossomed into one of the nation’s best, clearing 6-foot-8 as a sophomore.

“One thing I could do was jump,” he said.

That plus his height eventually drew Jones into basketball, where almost all his experience came within the confines of the team. He rarely played in pickup games.

“In the NBA, guys talked about playing at Rucker, playgrounds like that,” he said. “I didn’t do that. Never. No playgrounds. No parks. No AAU.”

After leading South Mecklenburg to a state title, Jones headed to Chapel Hill. His father and brother pushed for Oklahoma, but the homebody resisted.

“Too far,” he said.

As a North Carolina sophomore, Jones developed pericarditis – inflammation of tissue around the heart. Though Jones hadn’t been one of the 150 invitees, coach Dean Smith suggested he try out for the 1972 Olympic team.

He got lucky. Head coach Hank Iba and assistant Bob Knight were defense-focused. They valued Jones so much, he not only made the team but started.

“I didn’t start for my college team and here I was starting in the Olympics,” he said.

Jones was in Munich when the Israeli athletes were taken hostage and killed, when the Russians stole the gold-medal game, when his downcast team spurned silver medals.

“The Israeli massacre took the joy away,” said Jones. “We had a reunion five years ago. Someone found out who made Olympic medals and got a second set of gold medals struck for us. They’re nice, but in my mind we deserved the real ones.”

While at Carolina Jones suffered his first seizure. George Karl, his roommate and a future NBA coach, nearly lost some fingers trying to keep Jones from swallowing his tongue.

Smith, whom Jones credited with changing him from a good defensive player to a great one, called Jones the most versatile defender he ever coached.

“When we played North Carolina State,” Smith said in 1994, “I could put Bobby on either 7-4 Tom Burleson or 6-4 David Thompson.”

Jones was a Carolina senior when he found a new focus. Prodded by his fiancee – he and Tess are married 45 years – the half-hearted Baptist became a born-again Christian.

“I thought Christians had to be missionaries in Africa,” he said. “I thought they were wallflowers, little non-aggressive people on the edge of society. But my girlfriend was pretty and I wanted to keep dating her so I went to church and Bible study.”

His conversion was deep and thorough. In the NBA, Jones wouldn’t grab the jerseys of players he guarded. When he won an award sponsored by Seagram’s distillery, he donated the $10,000 prize to charity and asked that the banquet be alcohol-free. And the only time he felt the urge to hit an opponent – the physically imposing Maurice Lucas, then a Knick – a Bible verse popped into his head, calming and perhaps saving him.

“There’s nobody nicer,” Barkley said of his ex-teammate, “If everybody was like Bobby Jones, the world wouldn’t have problems.”

ABA beginnings

Drafted by Houston with 1974’s fifth overall pick, Jones signed instead with Denver of the ABA. His coach was Larry Brown, like Cunningham a disciple of his college coach, Smith.

“God was looking out for me,” Jones said.

At Denver, Jones was an All-Star who honed his defense guarding forwards such as Erving, George Gervin, George McGinnis.

“There were so few ABA teams, you played one of those guys every night,” Jones said. “There was always somebody to give you a challenge. They helped me understand how strong guys were, what they liked to do, how to try to thwart them.”

Jones endured two more epileptic seizures as a Nugget, spooking management enough that in 1978 they dealt him to the 76ers for McGinnis.

“When I had those seizures, they gave me phenobarbital, a depressant,” he said. “The doctor said it would slow my reactions, that I wouldn’t be the same player. The drug spaced me out, but I said, ‘If God wants me to keep playing, I will. If not, I’ll find something else.’ Eventually things worked down.”

Jones’ first day in Philadelphia was eye-opening -- and eye-closing. He collided head-on with a pick-setting Dawkins during practice. The newest Sixer dropped unconscious to the floor. When he awoke, Dawkins was looming over him.

“Welcome to the Sixers,” he said.

In the locker room, when Jones revealed his epilepsy, trainer Al Domenico started a pool on where the first seizure would occur.

“It broke the ice,” he said. “I appreciated that.”

With Jones complementing Erving, Cheeks, and Andrew Toney, Philadelphia averaged 55 victories in his first four seasons, twice reaching the NBA Finals.

“At Denver, we had really good teams, but they’d ship somebody out every year. In Philly, the nucleus was there four, five years. Julius and I got to know each other so well he could look in my eyes and know what I wanted to do.”

Then, before the 1982-83 season, Malone arrived. Jones and the Sixers got their parade.

“Moses was the final piece,” Jones said. “Caldwell [Jones] was a great center but limited offensively. Darryl was mercurial. Moses was a beast, relentless. When he was with Houston, every time I blocked his shot, he’d get it back, score, and get fouled.”

Jones hasn’t had a seizure in 20 years. He still takes phenobarbital daily. If his body has found a comforting routine, so has his spirit.

“I’m enjoying life,” he said.

He returned to Philadelphia when Malone’s number was retired and when a statue of him -- diving for a ball, of course -- was dedicated at the 76ers practice facility.

Of his ex-teammates, Jones remains closest with Clint Richardson, another Christian. He said Toney, a school administrator in Louisiana, keeps them all connected and informed via email.

The years have obscured his sensational career as they have his boyish features. As lunchtime neared, Phil’s Deli filled. Jones went unrecognized. It was a familiar sensation.

“My son played basketball and picked my number, 24. I was so happy,” Jones recalled. “When he got in the car, I asked him why. He said, `Somebody took Michael Jordan’s 23. That’s as close as I could get.’ ”