In ‘The Last Dance,’ Michael Jordan shows us who he really is. And tramples a man’s memory to do it. | Mike Sielski

Former Bulls GM Jerry Krause, who died in 2017, could be an insecure jerk. But this documentary was Jordan's chance to settle a score with a "villain" who isn't around to fight back.

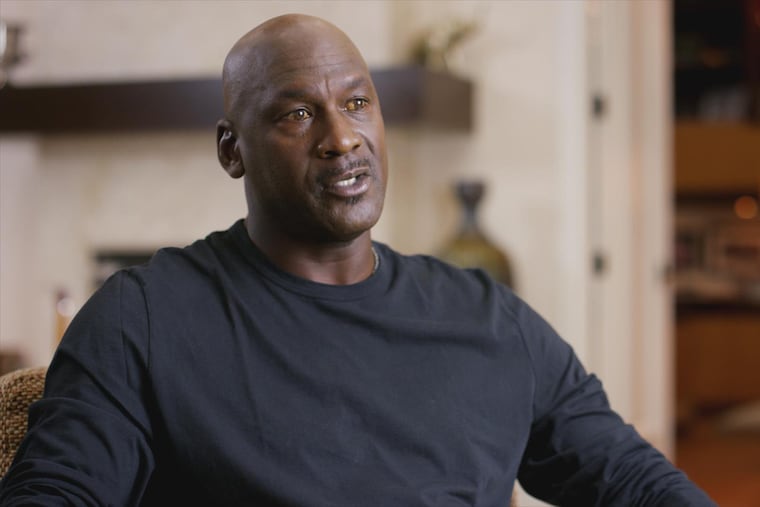

What Michael Jordan has done to Jerry Krause over the last three weeks is deliberate and dishonorable. With each episode of The Last Dance, ESPN’s 10-part documentary about Jordan and the 1990s Chicago Bulls, it becomes harder to separate the entertainment and nostalgic value of the series from Jordan’s agenda, from his desire to preserve his legacy, settle scores, and rub his status and greatness in the faces of his real and perceived rivals — one, in particular.

Krause — the Bulls’ general manager for 18 years, including the eight-year period when they won six NBA championships — has served a convenient function throughout The Last Dance. He has been the series’ primary source of narrative tension, and he has been Jordan’s punching bag. He insisted that the Bulls needed to be rebuilt after the 1997-98 season, and he dared to suggest that he deserved more credit for the dynasty than most people, Jordan foremost among them, were willing to give him. All these years later, even after Krause’s death in 2017 and his posthumous induction into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, Jordan apparently can’t abide that Krause — with a physique like a honey pot, with an irascible disposition, with his own opinions about how to operate an NBA team — had any role to play at all in the Bulls’ success.

So, with Jordan’s production company having partnered with ESPN to deliver The Last Dance, with the documentary’s pretense of balance and fairness subject to its protagonist’s veto, viewers are privy to Jordan’s asking Krause at practice one day, “Are those the pills you take to keep you short, or are those diet pills?” They’re in the locker room after Game 6 of the 1992 NBA Finals, when Jordan, about to light a victory cigar, tells Krause, “You can’t have one. It’ll stunt your growth.” They see Jordan patiently answering all the media’s repetitive questions, and they see Krause subtly raise his middle finger while walking past a cameraman. They see Krause, instead of working to re-sign any of the players already on the Bulls’ roster, traveling to Europe to negotiate a contract with draft pick Toni Kukoc, and they see Jordan’s still-simmering anger about it: "He’s willing to put someone in front of his actual kids.”

They are served the rewarmed controversy over whether Krause said, “Players and coaches don’t win championships; organizations do” or whether he said, “Players and coaches alone don’t win championships.” They hear Krause in a two-decade-old TV interview sputtering to say he was misquoted, and they hear Jordan’s present-day response: “For him to say that is offensive to how I approached the game.”

Well, good for you, Michael. You got in another punch after the poor kid in the schoolyard went down and would never get up again. This was never a fair fight even when Krause was alive. Jordan was always going to get the benefit of the doubt from the public and the basketball community. Just look at the two of them. Jordan was smart and sharp and handsome, the best basketball player ever, the wealthiest and most powerful athlete ever, and Krause was always the easiest of targets: defensive, insecure, overweight, his shirts always sprinkled with a fine white powder that was doughnut sugar, dandruff, or a mixture of both.

One of them was the essence of cool. One of them was the furthest thing from it. In sports, sometimes picking a side is nothing more than a popularity contest that could play out in the halls of any high school — a contest that Krause was never going to win. Jordan called him “Crumbs.” Everyone laughed.

‘Michael, he’s got a needle’

“Jerry was a complicated little guy,” said former 76ers general manager Pat Williams, who was the Bulls’ GM from 1969 to 1972, when Krause was the team’s lead scout. “He had grown up undersized and was a constant, constant target of riding and verbal abuse, I guess you could call it. The scouts could be really, really tough on him. Yet, he was like one of those dolls with the weight on the bottom. They stand there, and you push them down, and they come right back up, those toys. That was him. He just would not be denied.”

Williams admired Krause’s acumen enough to hire him in 1976 to scout for the Sixers, only to have Krause leave a few months later to become the Bulls’ player-personnel director. “Here was the problem: He had to be in the middle of it — on the road, around the coaches” and players, Williams said in a phone interview. “And Michael, he’s got a needle. Oh, he had a needle.”

The Last Dance represented Jordan’s latest chance to be a bigger man, to acknowledge Krause’s contributions to the Bulls, and still he couldn’t bring himself to do it. Nothing has changed from Jordan’s 2009 Hall of Fame induction speech, the most embarrassing — and maybe the most honest — moment of his basketball life, when his remarks devolved into petty taunts and I-told-you-sos to anyone who had stood in his way or didn’t kiss his feet. During that speech, Jordan showed the same contempt for Krause that he has throughout The Last Dance. “The organization didn’t play with the flu in Utah,” he said that night.

No, it didn’t. But then, Jordan didn’t find Scottie Pippen at Central Arkansas and draft Horace Grant out of Clemson, didn’t have the patience to wait three years for Kukoc to join the Bulls, didn’t sign John Paxson and trade for Bill Cartwright and Dennis Rodman and Steve Kerr, didn’t see the genius of Tex Winter’s triangle offense, and didn’t rescue Phil Jackson from the Continental Basketball Association’s Albany Patroons and give him a shot to be an NBA head coach.

Even after all those astute acquisitions and moves, no one remembers those teams as the Krause Bulls. They’re the Jordan Bulls, now and forever, and if he is still this bitter about Krause’s calculation that their excellence was bound to wane after the ’97-98 season, maybe Jordan should take a hard look at himself and his own actions. What do you think did more to prevent the Bulls from winning another championship or two: Krause’s belief that it was time to start fresh, or Jordan’s decision in 1993, in his physical and mental prime, to retire from basketball and try playing professional baseball in the White Sox organization?

“I would never let someone who’s not putting on the uniform and playing every day dictate what we do on the basketball court,” Jordan says early in the documentary, and that philosophy apparently has carried over to his ownership of the Charlotte Hornets. Since Jordan bought a minority share in and took over basketball operations for the franchise in 2006, Charlotte has had 11 losing seasons in 14 years and has never won a playoff series. For all the torment that he inflicted on Krause for being chubby and ungainly and eager to take the Bulls in a new direction, Jordan hasn’t done Krause’s job much better than Krause would have done Jordan’s.

The perfect villain

The construction of any great team, let alone one that was as great for as long as those Bulls teams were, is never a zero-sum exercise. It never comes down to just one person. But out of ego and for the sake of a grudge, Jordan is happy to indulge in the same reductive thinking that characterizes so much of the discussion and coverage of sports these days. Otherwise, there would be no foil for him and less conflict for ESPN to mine.

Even if the coronavirus pandemic hadn’t wiped away the entire sports calendar, even if the NBA and NHL playoffs and the Major League Baseball season were rolling along as usual, ESPN merely would have waited until early June, as originally scheduled, to air The Last Dance. The NBA Finals would have been wrapping up then — perhaps with LeBron James and the Los Angeles Lakers at the center of a celebration — and the same cycle could churn. A couple of episodes would air on a Sunday night, and the network would feed content to its own programming — SportsCenter and Get Up and First Take — for a couple of weeks thereafter.

That’s how the game is played, and in the absence of a full-fledged MJ-LeBron debate, Krause can be the perfect villain, the ideal contrast to Jordan. Sure, Isiah Thomas and the Detroit Pistons put “the Jordan Rules” into effect and pounded the Bulls over two playoff series, then refused to shake hands after the Bulls finally beat them in 1991. The Bad Boys make for fine bad guys. But at least Thomas and his teammates were still available to be interviewed for The Last Dance. Aside from a token compliment here or there from Kerr or Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf, no one is standing up for Krause in the documentary: no family member, no colleague, no one.

There is something cheap, unseemly, and quite telling about the inclination to continue bullying a man who isn’t around to defend himself. To Michael Jordan, Jerry Krause was a laughingstock when he was building the Bulls’ dynasty, and he remains a laughingstock now, three years dead. A good documentary is supposed to unveil the truth, and by that standard, The Last Dance is a genuine achievement. All it took was the trampling of a man’s memory to reveal Michael Jordan for who he really is.