Philly referees have dominated NBA officiating for decades. Here’s why.

Throughout the NBA's 75-year history, one tradition that has endured is the quantity and quality of referees from the Philadelphia area.

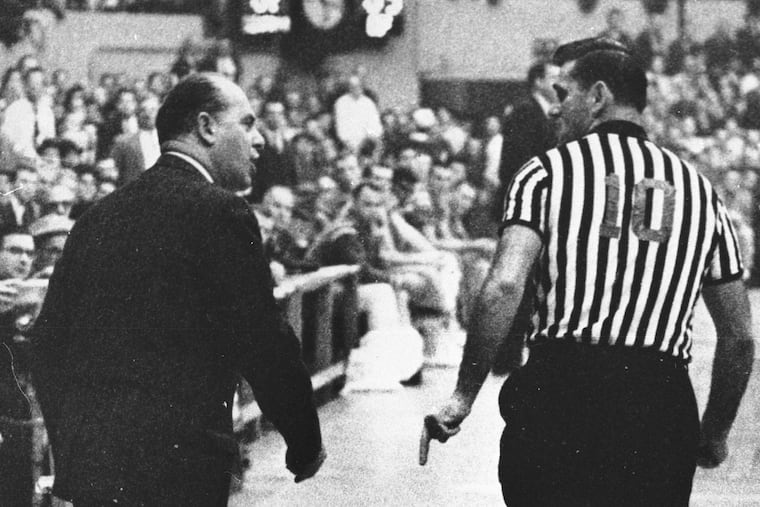

NBA players and coaches occasionally murmured about the league’s unusually large collection of Philadelphia-area referees, but none as loudly as Red Auerbach, the longtime Boston Celtics coach and executive.

“Every league meeting, he’d rant and rave about all the refs from Philly,” said Ed Rush, once the NBA’s supervisor of officials. “We’d say, ‘Red, some of these guys are from Trenton or Western Pennsylvania.’ And he’d say, ‘That doesn’t matter. They went through Philadelphia.’ He was probably the loudest voice in the league and he was always on his soapbox about that.”

That discontent exploded one night following a Celtics loss, when Auerbach, upset by Jake O’Donnell’s officiating, tried to kick down the door to Boston Garden’s referee room.

“He was shouting, ‘Yo, Philadelphia Jake, you blankety-blank, come out here!’ ” recalled O’Donnell, a Delaware Countian who was an American League umpire before moving to the NBA. “He was a loudmouth and he hated referees, especially Philadelphia referees.”

Throughout its 75-year existence, the NBA’s rules and records, its uniforms and arenas, players and equipment have undergone continuous evolution. But one tradition that has endured is the quantity and quality of referees from this area.

These Philadelphia officials, past and present, wear their brotherhood like a badge of pride. Each offseason they gather for a dinner, actually a cocktail-fueled homage to common roots and shared experiences.

Many who have attended would be on any objective list of the best-ever referees — Rush, O’Donnell, Earl Strom, Joe Crawford, Joe Gushue, Jack Madden, John Vanak, and Steve Javie. Not far behind that elite group in reputation are several others who earned their black-and-white stripes here — Duke Callahan, Mark Wunderlich, Ed Malloy, Leroy Alexander, Ed Middleton, and Billy Oakes.

» READ MORE: While Joe Crawford was a ref in the NBA, his brother Jerry was a Major League Baseball umpire

Maybe the best way to judge this group’s historic impact is its over-representation in the NBA Finals, an event restricted to the top-rated officials. For 59 consecutive seasons, from 1961 through 2019, at least one Philly ref, and usually more, worked the championship series.

Many are retired or deceased now but, though much more geographically diverse, the active referee roster still includes several from this area — Malloy, Aaron Smith, Mark Lindsey, Central High grad Tom Washington and Millersville University product Ashley Moyer-Gleich. And while Crawford, Callahan, and Wunderlich stepped aside during the last decade, they continue the work as NBA administrators who advise, train, and rate the 5,000 officials trying to access the sport’s premier stage.

Even two of history’s most notable non-Philadelphia referees, Mendy Rudolph and Sid Borgia, had local ties. Rudolph, though raised in Wilkes-Barre, was born here. Borgia, a New Yorker, had a summer home in Wildwood.

Roots run deep

This connection between a city and a profession runs so deep that it continues to prompt questions like Auerbach’s: How did it begin? How has it been sustained? And why are Philly referees so often better than their peers?

There are no simple answers, said the officials themselves. Certainly the quality of basketball here helps develop quality refs. But just as important are geography, personal connections, word-of-mouth and, maybe most importantly, that feisty Philly attitude.

“One thing these guys all had that really made them successful was a little edge,” said Rush, 79, who at 24 went from coaching football at Marple-Newtown High to officiating in the NBA and is now retired in California. “And that’s a Philly thing. You would know Joe Gushue was running the game. You’d know without question that Joe Crawford was running the game. The game’s not going to run them. So if you’re running the league, you want to make sure you put someone out there you can trust, someone who will take care of all the junk.”

Crawford, 69, who left active refereeing in 2016 and lives in Newtown Square, said he’s been asked “a million times” how Philadelphia has produced so many top-flight officials.

“I tell them it’s the basketball,” Crawford said. “I was working twice a week in the Baker League even when I was in the NBA. They were pro players and they didn’t care that I was in the NBA. They were coming after me and I had to deal with that. When there are really good players like there are in Philly, you get better as a ref. You also learn to work games in tough neighborhoods. That’s where intestinal fortitude comes in.”

Intestinal fortitude is mandatory. O’Donnell, 84 and retired in Florida, suggested that as a young referee he preferred working games in tough Philadelphia neighborhoods. It steeled him for all those nights when NBA coaches and players cursed him and 20,000 angry fans screamed for his head.

“I was an orphan. I grew up in three homes, ran away from the last one at 15, so I was tough anyway,” said O’Donnell, who eventually settled in Clifton Heights. “I wasn’t afraid to go anywhere. I liked working in the city because they were tougher and that made me tougher.”

» READ MORE: Earl Strom was inducted into the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame last year

The same but different

Philly refs aren’t carbon copies, but they do share plenty of demographic similarities. Most were Catholic and white. Many were athletes themselves. Madden, Strom, and Javie umpired. And most honed their craft in the old Eastern League, where Rudolph’s father was the commissioner, or in peculiarly Philadelphia-area hoops institutions like the Baker League, the annual Gold Medal Tournament, or Margate and Wildwood summer leagues.

Not all grew up in Philadelphia or its surrounding counties. Madden was from Trenton, Vanak the Coal Regions. But they refined their skills here and joined the Philly fraternity.

“When there are really good players like there are in Philly, you get better as a ref. You also learn to work games in tough neighborhoods. That’s where intestinal fortitude comes in.”

The begetting in this tight-knit community is no less prolific than that in the Bible. Before the league broadened its search for referees and stiffened its vetting process, the Philadelphia crew uncovered a lot of referees without leaving home.

Vacationing in Wildwood, Borgia spotted Gushue officiating an ocean-side game. Gushue mentored O’Donnell, who served the same role for Crawford, who then helped Wunderlich and three fellow Cardinal O’Hara grads in Malloy, Callahan, and the now-disgraced Tim Donaghy. Wunderlich and Crawford have guided Smith and Lindsey.

Smith, a graduate of West Chester East High and West Chester University, straddled both the old and new ways of getting the job. He made it through the NBA’s rigid auditioning, but also got a personal assist from his local predecessors.

“Aaron went through the system, but he lives up the street from Mark Wunderlich and he watches tape with Mark,” said Crawford. “He’s been over my house watching tape. Mark Lindsey the same thing. See that advantage?”

High standards

That generation-to-generation nurturing produces peer pressure, Crawford said. Younger Philly refs want to live up to their predecessors’ high standards.

“I wanted to impress those guys,” said Crawford. “It wasn’t important for me to get accolades from players and coaches, but I wanted Joe Gushue to say, ‘Joe, you’re a really good ref.’ ”

That pressure intensified as the number of Philly referees expanded.

“When I was first hired [in 1986] there were only 30 referees and probably 9 or 10 were from the Philly area,” said Javie.

Rush, who still operates clinics for aspiring refs, said that for a long time the league, realizing it was top-heavy with Philadelphia and New York officials, tried unsuccessfully to widen its search.

“We were looking for guys with inner-toughness,” said Rush. “The officials on the West Coast and even the Midwest didn’t have the same background. They didn’t have the Baker League. They didn’t have these outdoor leagues in Philly or New York, all those training grounds. They’d ask, ‘Where do I get games like these?’ And I’d say, ‘Well, you’ve got to come to Philly or New York.’ ”

Crawford insisted there was no favoritism at work in the way this whistle-blowing society developed. But it’s clear that geographic convenience played a part. The league offices were in New York, and most of the referees, as well as those hiring them, were from there or Philadelphia.

Philly rules

By the 1978 Seattle-Washington NBA Finals, Philadelphia officials were ascendant. Of the 14 referee slots in that seven-game series, nine went to six locals — Rush, O’Donnell, Gushue, Vanak, Madden, and Strom.

“We sort of dominated the league,” said O’Donnell.

The trend likely started with Jocko Collins. A colorful Philadelphian who also scouted for the Phillies, he was a part-time ref in the NBA’s early years and in 1954 became its first supervisor of officials. Three years later he spotted Strom working a college game at the Palestra. That opened the pipeline. Gushue arrived in 1961, Vanak in ’62, Madden in ’65, Rush in ’66, O’Donnell in ’67.

“One guy helped the next,” said Crawford. “Jake O’Donnell, who was a major-league umpire, did a favor for my father [Shag, also an MLB ump]. He came to see me work a CYO game at Mother of Good Counsel. All my father had to do was pick up the phone and Jake came to watch me, to give me directions. That guy in St. Louis wasn’t getting that because there wasn’t anybody out there.”

For his part, Crawford has been a prodigious scout. He found Wunderlich, a Lansdowne-Aldan High grad, officiating at Havertown’s Bailey Park. Through his O’Hara connections, he helped identify Callahan and Malloy.

“When people ask me how come there are so many Philly refs, I tell them it’s a pride thing,” said Javie, 66, now a Catholic deacon in Bucks County. “You want guys from the area to succeed. Joey Crawford has done a tremendous job with that. There are stories of young kids knocking on Joey’s door and asking him to watch a video of them working. Joey never refused.”

Because of COVID-19, the Philly refs postponed their dinner this offseason. The last was at the Union League, where chef Marty Hamman, like Crawford, Malloy, and Callahan, an O’Hara grad, prepared four gourmet courses.

“It’s been a wonderful tradition,” said Javie, who plans the affairs. “It’s one reason the referees from the Philly area are such a tight-knit group. It’s really a great bunch of guys that have bonded through the years. I’m proud to be a part of it.”