James Harden and Joel Embiid have to be the modern Doc and Moses. The Sixers’ title hopes depend on it. | Mike Sielski

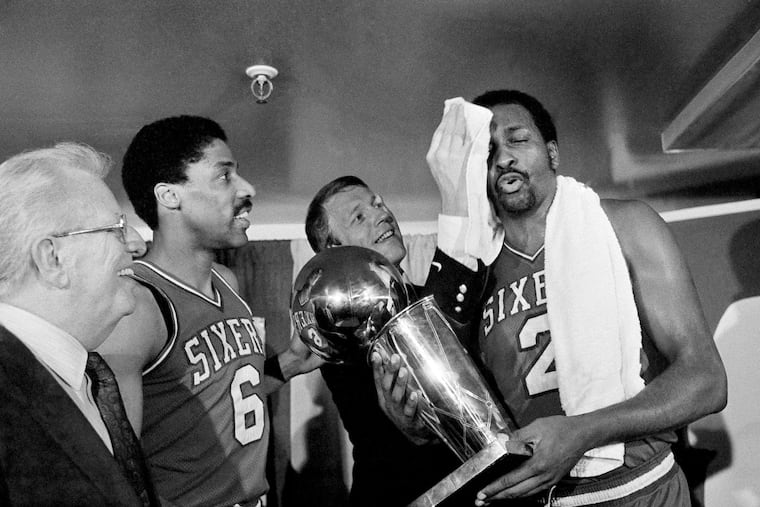

No two superstars ever melded better than Julius Erving and Moses Malone during the Sixers' 1982-83 championship run. Doc Rivers faces the task now that Billy Cunningham did then.

Down in southeastern Florida, Billy Cunningham can live a snowbird’s life thanks to the warm weather and a clear mind, free for nearly 39 years now from the kind of pressure that Doc Rivers and these 76ers can only begin to imagine. Julius Erving. Moses Malone. How does a coach not win a championship with those two in his lineup? What would have been Cunningham’s legacy if he hadn’t?

Even at 78, Cunningham still comes off as the coolest guy in any room, but make no mistake: If he and the 76ers hadn’t swept the Lakers in the 1983 NBA Finals, if they had kept winning 50-plus games season after season and never finished the job, the failure would have haunted him forever. Instead, Erving and Malone established the franchise standard for superstar integration, one that Joel Embiid and James Harden still only aspire to meet. And the last man to shepherd the Sixers to the mountaintop was quick to remind people to put the pom-poms down and remember what the truest test of the Embiid-Harden partnership will be.

“Right now, everything is beautiful. It’s rosy,” Cunningham said Monday in a phone interview. “They’ve won two games. Everybody is, ‘See, that’s why we did it.’ Well, we don’t know anything yet. You’ll find out when they get to the conference finals and how they respond.”

» READ MORE: Tobias Harris’ role with Sixers changed after the James Harden trade. And he’s accepted that.

Good for Cunningham for injecting a little patience into the evaluations of an experiment whose results remain uncertain. Harden has made the Sixers a more dynamic offensive team so far, fitting seamlessly in pick-and-roll situations with Embiid, taking Tyrese Maxey under his wing and elevating Maxey’s play and production. But so far consisted of two opponents — the Timberwolves and Knicks — targeted for the league’s play-in tournament, and Cunningham can be forgiven for defaulting to skepticism when asked about a team whose members are soon enough supposed to be riding parade floats and waving at giddy crowds.

The Sixers and their fans had a half-decade of supposed to until the late summer of 1982, when the team agreed to send Caldwell Jones and a first-round draft pick to the Houston Rockets. In return, the Sixers got Malone, already the NBA’s MVP twice, already inclined to defer to Erving. Malone had made his professional debut in 1974 as a 19-year-old in the ABA, just when Erving was the upstart league’s dominant figure. “Moses’ hero was Julius,” Cunningham said.

In September 1982, Erving had embarked on a goodwill tour of China with several other NBA players — M.L. Carr, the Celtics’ bench-warmer/towel-waver among them — and was feeling less than sanguine about the Sixers’ chances to win a championship. The Lakers, having beaten the Sixers in the Finals in 1980, having beaten them again just weeks earlier, had drafted James Worthy. The Celtics had added a solid supporting player or two. In Guangzhou, Erving learned that general manager Pat Williams had dealt away Darryl Dawkins for a first-round draft pick, and Carr taunted Erving over the Sixers’ offseason inertia. “It’s over,” Carr told him. “You guys gave up your best big man.” Days later, though, upon checking into a Hong Kong hotel, Erving received a message from the Sixers that the Malone trade had become official.

“M.L. Carr has heard the news as well,” Erving wrote in his autobiography, Dr. J, “and when I see him down in the lobby, he’s shaking his head. ‘You guys just won the title.’”

Nothing is ever so smooth, and the manner in which those Sixers steamrolled the NBA — a 65-17 regular-season record, 12 victories in 13 postseason games — makes it convenient in retrospect to forget the potential pitfalls that awaited them. Erving’s salary during the 1981-82 season had been $400,000 and would more than double for ‘82-83. But even that raise didn’t put him in the same stratosphere as Malone, who had signed a six-year, $13.2-million offer sheet with the Sixers.

“Looking out for myself,” Erving told reporters at the time, “I’m still assessing where I fit into the picture. That will have to be clarified soon.”

All pro athletes have egos, and when they keep score among themselves, the first stat line has a dollar sign over it. The potential for tension between the two stars was real, or at least seemed to be, except that, according to Cunningham, Erving never made Malone’s money an issue. He didn’t go stomping into owner Harold Katz’s office, and if he was at all disgruntled over suddenly being the second-highest-paid player on the team, he never let it bleed into his play during practices or games and never expressed it to his coach. Besides, Malone was so obviously the ideal addition to the roster, his rebounding and work ethic and tenacity the missing keys to a championship, that Erving or any other Sixers would have been a selfish fool to foul things up.

“I never thought it was going to be as easy as it was,” Cunningham said. “I really didn’t. But it was like they’d been playing together for years. We were a team that was lacking a real presence in the middle physically, and that’s what Moses brought us. It wasn’t anything I did. They complemented each other beautifully. They got along great personally. It was just the respect that they had for each other.”

» READ MORE: 60 years later, Chamberlain’s 100-point game still leaving coaches and players awestruck

That’s the mark that Embiid and Harden have to meet. The Sixers have played beautiful offensive basketball since Harden arrived, and maybe Rivers’ experience handling superstars in Boston and Los Angeles makes him the perfect coach to meld Embiid and Harden into a single-minded machine. Maybe. Two games. He’ll be lucky if it turns out to be as easy as it has been so far. He’ll be lucky if he turns out to live the life that Billy Cunningham does now and did then.