The troubling, tragic, and mysterious story of former Sixers draft pick Terry Furlow | Mike Sielski

The Sixers made Furlow the 12th pick of the 1976 NBA draft. He played one year for them, then embarked on a tumultuous career and life.

The stretch of highway that Terry Furlow was driving in the early hours of May 23, 1980, was already notorious. Near Cleveland, Interstate 71 bisected the village of Linndale, so tiny that it barely qualified as a village. Less than one-tenth of a square mile, it had just 129 residents, and a significant portion of its annual revenue, thousands of dollars, came from traffic fines. A police cruiser often lay in wait on a side street, just where the speed limit dropped to 25 mph. Everyone in northeast Ohio knew: To speed through Linndale was to fly into a spider’s web.

Through the black of night, Furlow was barreling toward that trap, pushing his Mercedes to 55 mph and beyond. Nearly four years had passed since the 76ers had selected him in the first round of the 1976 NBA draft. He was 25 years old, 6-foot-4, lean, with a thin mustache, his arms hilled with muscle. He had what one writer called “a perfect jump shot.” But after his rookie season with the Sixers, in which he was the last man on the bench for a star-laden team that reached the NBA Finals, he had been traded three times, playing for the Cleveland Cavaliers, the Atlanta Hawks, and, finally, the Utah Jazz.

He could be lighthearted, cocky, surly; his moods were unpredictable. So, increasingly, was he. In his car were a copy of the Jazz’s playbook, several Jazz warmup shirts, three open cans of beer, and a marijuana cigarette. Cocaine powder dusted one of his pants pockets. Traces of cocaine and Valium flowed in his bloodstream. A tractor-trailer trundled along the road in front of him.

As he approached Linndale, he pressed his right foot down on the gas pedal. The Mercedes accelerated, its speedometer needle quivering near the 120-mph mark, the sports car zooming forward before cutting to the right, across I-71, to pass the truck. The danger in which he had now placed himself – the alcohol, the drugs, the speed, the choices – had been building since before he arrived in Philadelphia. He had long given up trying to stop it.

A team that didn’t need him

Over the 40 years since that night, the Sixers have made 43 first-round picks in the NBA draft, choosing players ranging from the immortal (Charles Barkley, Allen Iverson) to the underwhelming (Markelle Fultz, Shawn Bradley). None of them, though, combined basketball talent and a penchant for self-destruction in the same proportion that Furlow did. He never had a chance with the Sixers, and something deep within didn’t allow him to give himself a chance once he left them.

“He was competitive as hell,” said Mike Fratello, who was an assistant coach with the Hawks under Hubie Brown during Furlow’s tenure in Atlanta. “He’d fight you in a game, and he understood the toughness of the NBA. There were some other things that he just couldn’t get past.”

Born in Camden, Ark., Furlow moved to Flint, Mich., with his family when he was 2. Four years later, his father left. “I’m still trying to adjust to that,” he said ahead of his senior season at Michigan State, where he blossomed into one of the best shooting guards in the Big Ten. He had led the conference in scoring as a junior, then did it again, averaging more than 29 points a game as a senior, including a 50-point performance in a victory over Iowa. “Terry,” Gus Ganakas, his coach at Michigan State, once said, “was the hardest-working player I ever had.”

» READ MORE: THE 24 HOURS THAT CHANGED SPORTS, AND SOCIETY

He had a steady girlfriend, Charlice Davis. He earned a high grade in a course taught by Charles Tucker, a psychology professor who later became the agent to one of Furlow’s closest friends: Magic Johnson. He was a talented impressionist; he could mimic Clark Gable, Johnny Cash, and Mr. Magoo. During his junior season, Furlow was one of 10 Michigan State players who walked out of a team meeting, and were subsequently suspended for a game against Indiana, to protest several aspects of the basketball program, including their belief that a white player, Jeff Tropf, was starting ahead of several more-deserving black teammates. It was hardly a surprising stand and gesture for someone who kept a photo of Muhammad Ali in his locker.

Furlow had been involved in a few concerning incidents in college, too: The Big Ten had put him on probation for instigating a fight with Illinois’ Rick Schmidt, and he punched trainer Don Kaverman and teammate Pete Davis. But one scout, in particular, was enamored with him. With Jack McMahon, the Sixers’ top talent evaluator, hospitalized for months with a bad back, general manager Pat Williams had hired a replacement: Jerry Krause. Before leaving to become the Bulls’ director of player personnel, Krause told Williams that the Sixers’ pick, the 12th overall in the 1976 draft, should come down to a choice between two guards: Marquette’s Earl Tatum and Furlow.

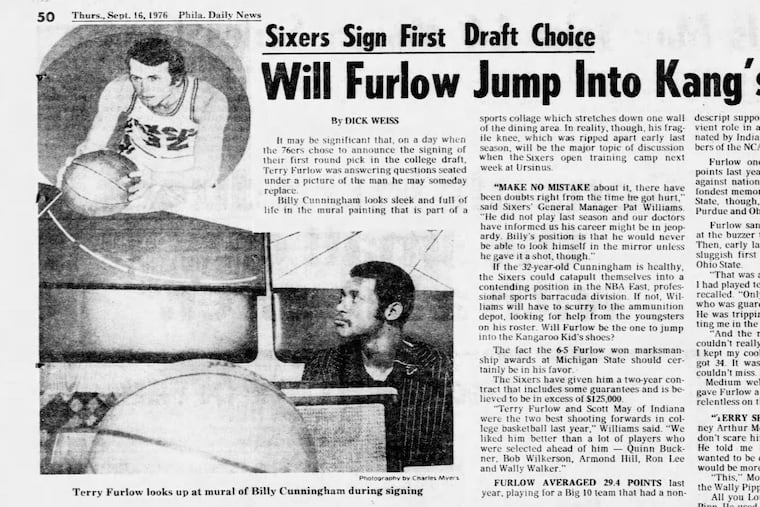

Believing Furlow was more likely to become a star, the Sixers picked him. Williams described him as “probably the best offensive player in the draft.” At Furlow’s introductory news conference, a Daily News photographer snapped a shot of him glancing up and to his right at a mural of Sixers star Billy Cunningham, who was 33, had appeared in just 20 games the previous year because of a knee injury, and whose availability for the ’76-77 was uncertain. The photo’s implication was obvious.

“You hope you can be with a team that needs you,” Furlow said then, “so I hope the 76ers need me.”

The 76ers did not need him. In October, they acquired Julius Erving from the ABA’s New York Nets, a move that made them championship contenders and that pushed Furlow, in the eyes of coach Gene Shue, to the bottom of an already-stacked roster. Erving took Furlow under his wing immediately. The two roomed together on the road and guarded each other during warmup drills. Furlow, in turn, was solicitous of Erving’s friendship, telling him stories about Michigan State, earning ribbing from teammates Darryl Dawkins and World B. Free whenever he’d follow Erving, puppy-dog-like, down the aisle of the team bus.

“He loved Dr. J.,” Free said. “Anywhere Doc was, he was.”

Except during games, that is. Furlow, as the Sixers’ fifth forward behind Erving, George McGinnis, Steve Mix, and Joe Bryant, played just 174 minutes all season, the fewest on the team. “He constantly felt frustrated,” Erving said in a 1980 interview. When Shue used Mike Dunleavy in a few late-game situations instead of him, Furlow seethed.

“I’ve waited five months to play,” he told the Wilmington News-Journal in April 1977. “Sitting on the bench isn’t my thing. I’d rather be on a lesser team and get extensive playing time than be on one that’s great and not playing. … I’m the best shooter on the team. I’ve proven that. So I just can’t understand it.

“This is the worst thing I’ve experienced. I bust my butt in practice and don’t play. I have pride in myself. By saying, ‘The hell with it,’ that’s not in the best interest for Terry. This is my life. Basketball has been my life. I would just like to do my job.”

That offseason, after going 50-32 during the regular season and losing in six games to the Portland Trail Blazers in the Finals, the Sixers traded Furlow to the Cavaliers for two first-round draft picks – quite a windfall for a player who had contributed so little and complained so loudly. “He had value,” Williams said in a phone interview. “There were just no minutes for him.”

At the time, Williams said, the only indication that Furlow might have been troubled in any regard came from a conversation with Michigan State alumnus and former Phillies pitcher Robin Roberts: “I do remember Robin saying to me, ‘That kid has some problems.‘” But Free and Mix said that nothing was apparent to them, and Mix noted that Furlow didn’t play enough for anyone on the Sixers to pick up on any deterioration in his game, which would have hinted that something was wrong.

Still, there had to be suspicions. Not long after the trade, one member of the Sixers’ front office, when asked about Furlow, told The Inquirer, “Someone didn’t do their homework.”

‘I am going to dominate’

The Cavaliers had qualified for the playoffs in 1976-77, but they were not at the Sixers’ level. They seemed a better fit for a young, promising player like Furlow, the kind of team he had wished he could play for. “This is an opportunity,” he said in October 1977, “and I’m an opportunist.”

In what would become a pattern throughout Furlow’s career, though, circumstances conspired against him, and he couldn’t help but submarine himself. He missed two months of the ’77-78 season with a viral infection, and when he was healthy, he clashed with Cavaliers coach Bill Fitch, at one point either challenging him or accepting a challenge from him – depending on whom you believed – to fight. He lasted a season-and-a-half with the Cavs before they traded him to Atlanta for Butch Lee on Jan. 31, 1979. The Hawks had a surplus of point guards, Lee among them, and the team’s coaches – Brown, Fratello, Frank Layden – wanted another scorer.

“We said, ‘We know the problems,’” Brown said in a phone interview. “But we felt we would give him a chance because he was tremendously talented.”

Under Brown, the Hawks ran a disciplined, set-heavy offense, designed to free their best players for open, easy shots – the ideal system, one would think, for Furlow to thrive. He needed just a sliver of space to release and make a jumper. In April 1979, for instance, Brown was ejected in the second quarter of Game 2 of the Hawks’ best-of-three first-round matchup against the Houston Rockets. Now in charge of the team, Fratello used a new play, “14,” in which Furlow and Dan Roundfield isolated themselves on one side of the floor and worked a pick-and-pop, throughout the second half. “Anytime we needed a bucket,” Fratello said, “we called ’14.’” Furlow shot 5-for-10 from the field in the third and fourth quarters, scoring 12 points, and the Hawks won, 100-91, to sweep the series.

“That’s what he was capable of,” Fratello said. Yet more often than not, Furlow bristled at the constraints of structure. “Rather than catch it and shoot it,” Fratello continued, “he’d catch it, turn and face, and wait for the defender to catch up. It was almost like he wanted to turn it into this one-on-one thing to show that he could beat his guy. It was like he was wasting the executing of the offense.”

Whether it was born of confidence, insecurity, or both, a compulsion too often overtook Furlow: He had to thrive on his terms and his terms alone, and he had to let the world know it. Nowhere was that compulsion on brighter display than in the Hawks’ next playoff series, a seven-game loss to the Washington Bullets in the conference semifinals.

In just 28 minutes a game, Furlow averaged 15.6 points, shot 50% from the field, and happily accepted the role as the series’ heel. He called Wes Unseld a “bully,” Elvin Hayes a “cheap-shot artist,” and the Bullets “crybabies. They bitch and moan all game. They have no class. They’ve got nobody who can stop me. I am going to dominate their guards physically and psychologically. … There is no guard on the Bullets [who] can stop me. Also, I’m going to establish the fact that I’m going to dominate their backcourt. I don’t want them to leave this series without knowing who Terry Furlow is.”

He spent the summer of 1979 telling his peers that he was going to be a superstar, and at training camp, he and Eddie Johnson, who had become friends, were to compete for the starting shooting guard spot. Those two factors – his off-court friendship and on-court rivalry with Johnson – were a powerful and poisonous cocktail for Furlow. Cocaine was regarded as the scourge of the NBA in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and Johnson would become one of the most infamous figures of that era. He played 10 years in the league and made the All-Star team twice, but the NBA, after suspending him for cocaine use several times, banned Johnson for life in 1987. He remains in a Florida prison after having been convicted of sexually assaulting an 8-year-old girl.

If Johnson couldn’t handle success, Furlow couldn’t handle failure. “Eddie came out and whipped Terry” in their training-camp faceoff, Brown said. “Terry’s personality could not accept that stark reality.” His behavior grew more erratic. He showed up late for the team picture. After a game in Detroit, he called teammate Armond Hill at 2:30 a.m. and asked him to enter Furlow’s hotel room, pack his bags, and take them to the airport. Furlow didn’t fly home with the team. Since the Hawks were off the next day, he said later, he wanted to stay in Michigan and spend time with his family. His four-bedroom home on the south side of Atlanta was sparsely decorated, with little furniture, but was constantly full of house guests, many of whom used drugs.

“I used to tell Terry, ‘Watch out for those people. They’re nothing but leeches,’” Davis, his girlfriend, said in a 1980 interview with the New York Times. “Terry liked people patting him on the back, saying, ‘You can really shoot that ball.’”

Twenty-one games into the 1979-80 season, with Furlow’s playing time and shooting percentage dropping, the Hawks traded him to Utah. “I wouldn’t conform totally to what Hubie Brown wanted,” Furlow once said. “Some players cannot take that on-your-back, taunting, cursing, swearing, hounding, you’re-getting-your-ass-whupped kind of stuff. I’ll tell you something else: When you play for the Atlanta Hawks, Hubie Brown is in control of your life.”

Furlow moved into a two-room suite in a Travel Lodge in Salt Lake City. “I can see a future here,” he said in February 1980, “and I can see something developing. It’s an attitude that we’re not going to stop at anything.” Layden, who had moved on from Atlanta to become the Jazz’s general manager, said in a recent interview that he was not aware of any drug use by Furlow before he traded for him. “I knew that afterwards,” he said.

Furlow averaged 16.0 points over 55 games with the Jazz. But he wanted to renegotiate his contract and was dissatisfied that Layden and the franchise declined to offer him a new deal. The tenacity and braggadocio that once marked his play faded. “He didn’t have a sustained effort,” Allan Bristow, one of Furlow’s teammates in Utah, said recently. “He was the kind of player who was not a self-motivator. He didn’t practice hard. I’m sure things came easy to him in college, but to me, he never sustained the effort playing-wise.”

Twice in a 17-day span that season, Furlow played against the Sixers and his old mentor. He scored 20 points in a 107-101 victory at the Salt Palace on Jan. 28, 1980, then had 22 in a 107-85 loss at the Spectrum on Feb. 13. After the first of those games, he told Erving that he would join him later for dinner, that he “had to do a little business” first. Erving waited at a restaurant in downtown Salt Lake City. Furlow never came.

“Terry was disappointed in himself,” Davis told the Times. “He hated his surroundings in Utah. He knew he would have to make a drastic change in his personality if he wanted to stay in basketball. He tried to cover his feelings, but I know he was deeply hurt. … He didn’t like to show his feelings, but in the last few months, his personality deteriorated badly.”

The Jazz finished 24-58, last in the Midwest Division. Once the season ended, Furlow traveled back to Atlanta to pick up his car. Then he drove north. He was supposed to attend a party in Cleveland for Clarence “Foots” Walker, who had been one of his teammates with the Cavaliers, but he didn’t show up. No one knew why.

Mysteries and questions

None of the traffic tickets that Robert Fousek, the police chief of Linndale, was accustomed to handing out could have prepared him for the horrifying scene along I-71 at 2:10 a.m. on May 23, 1980. A Mercedes had crashed into a steel utility pole. An eyewitness had watched the car pass a tractor-trailer, then veer to the right off the highway. The driver was pinned to the wreckage. It took rescue squads from two fire departments to extricate the body. At 3:05 a.m., Terry Furlow was pronounced dead on arrival at Deaconess Hospital in Cleveland.

“To lose his life the way he did was a shame, just a waste of talent, that he would die that way,” Fratello said. “But that was Terry. That’s who he was.”

Five hundred people, including Magic Johnson and Julius Erving, attended Furlow’s funeral at New Jerusalem Baptist Church in Flint. Johnson was one of the pallbearers. Erving, who according to a Sixers spokesperson was unavailable to be interviewed for this story, couldn’t shake Furlow’s death for years thereafter. “I’ve learned that you can’t always help,” he told the Daily News in September 1986. “You can only offer yourself.”

In eulogizing Furlow, the Rev. Odis A. Floyd said, “Those who knew him couldn’t help but like Terry. Life is filled with many mysteries, and it’s not for us to know why this tragedy happened.” Floyd left those mysteries unspoken, those questions unanswered, and Furlow took them with him to his grave at Gracelawn Cemetery. But they linger for anyone who reviews the reported details of the crash.

Samuel Gerber, the coroner who conducted Furlow’s autopsy, said at the time that he could not determine when Furlow had ingested the drugs in his system and, as a result, could not say for certain that their influence caused him to swerve off I-71. The Mercedes had slammed into the utility pole on the driver’s side. The impact had sheared the front wheel off the car and thrown the grill 500 feet down the highway. There were no skid marks on the road, no sign that Furlow had attempted to slow down or avoid the collision. “He never touched the brakes,” Fousek said. Wherever Terry Furlow intended to go that night, he was determined to get there as fast as he could.