A Wilt Chamberlain documentary used artificial intelligence to re-create his voice. The family is (mostly) thrilled to hear him again.

A new documentary on the legendary NBA player brings his voice to life using new technology combined with Chamberlain's own writings.

Olin Chamberlain called his uncle during the NBA playoffs in the early 1990s as Michael Jordan was making another run toward a championship. Chamberlain, then a teenage basketball player in Los Angeles, couldn’t call M.J., but he could get Wilt on the horn.

Except the phone line was busy again and again.

“I finally got him,” said Chamberlain, one of Wilt’s nephews. “I said ‘Come on, Uncle Dip. I know you’re better than this. You have to have call waiting.’ He said ‘Hey, if you weren’t the first person to call then it wasn’t meant for us to talk.’ He was laid back. He didn’t even have call waiting. He lived his own life.”

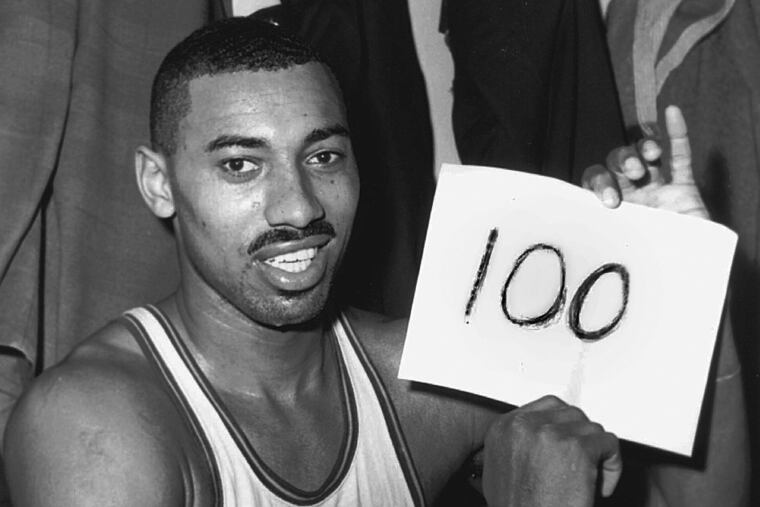

To the world, Chamberlain was the 100-point scorer who grew up in West Philadelphia and changed the game of basketball. To his family, he was “Uncle Dippy,” who had a voice as cool as his game.

And now they can hear Chamberlain — who died in 1999 — again after a documentary used artificial intelligence to re-create their uncle’s voice. The voice is used as the narration for Goliath, a three-part series about Chamberlain’s life that begins streaming Friday on Paramount+ and airs Sunday night on Showtime.

“He kind of had a deep but laid-back voice,” Olin Chamberlain said. “‘Hey, how ya doing?’ A relaxed voice. He didn’t seem pressured to us at all and lived his life the way he wanted to live his life. He didn’t allow others to dictate how he should live his life.”

The documentary includes interviews with Chamberlain’s family — including his remaining sisters, Selena Gross and Barbara Lewis — and basketball Hall of Famers from Sonny Hill to Pat Riley. Chamberlain’s former teammate Jerry West called the Big Dipper “one of the most misunderstood people I’ve ever seen.”

The film aims to allow the audience to better understand Chamberlain, who co-director Rob Ford said “has infinite layers.”

And there was no one better, the directors thought, to narrate Chamberlain’s story than himself.

“We wanted his presence to be felt,” said Christopher Dillon, Ford’s co-director.

His words

An actor was hired to read passages from Chamberlain’s three autobiographies and statements he was quoted as saying in news articles. The filmmakers then used an artificial-intelligence program to alter the tenor of the actor, matching Chamberlain’s voice based on hours of recordings gathered over the years.

“The emotion and the timing of everything that’s being spoken is done by a human being,” Dillon said. “It’s being done by an actor who we hired to embody Wilt and have emotion. What the A.I. does is change the pitch and tone of that person’s voice so they can sound like Wilt.”

A similar method was used in a 2021 documentary about celebrity chef and TV star Anthony Bourdain, who died three years earlier. That decision came under scrutiny as Bourdain’s family said they did not sign off on the use of A.I. to read an email Bourdain wrote to a friend. The directors of Goliath said they made sure to get the approval of Chamberlain’s family.

“What we did is take Wilt’s own words that he wrote and we’re just having an actor voice them and then we’re turning it into Wilt’s voice,” Dillon said. “But we’re not putting words into Wilt’s mouth.”

Olin Chamberlain said it sounds good. LaMont Lewis, another nephew, said it “almost felt like he was there,” but he knew his uncle well enough to pick up the nuances that the A.I. missed, like the way Chamberlain stuttered sometimes when he got excited. Michelle Smith, one of Chamberlain’s nieces, said the voice sounds natural.

» READ MORE: 40 years ago, the 76ers tried solving their backup center dilemma by bringing Wilt Chamberlain out of retirement

The documentary allowed them to again hear their uncle ― the one who never seemed to miss a family party and even let Lewis borrow his new sports car. But not everyone in the family seemed eager to hear Wilt’s re-created voice.

“Am I eager? No. Why would I want to? He’s dead,” said Chamberlain’s sister, Selina Gross. “What’s the purpose of that? I’m 88 years old and my brother would be 87. Why would I want to hear a dead person’s voice? I’m not into ghosts and things like that. I heard his voice when he was alive. We talked all the time, but he’s gone now. I don’t need to hear his voice. Why would I want to hear his voice?”

Gross’ daughter, Michelle Smith, said the artificial voice was so close to Chamberlain’s that she thinks her mother did not realize it was fake. Gross did not think the use of A.I. was offensive or disrespectful to her brother.

» READ MORE: A new documentary series follows the life of Philly basketball legend Wilt Chamberlain

“But what’s the purpose of it?” she said. “I don’t believe in it and I’ve never heard of my relatives, or anyone that I’m close to, come back and say anything, and I don’t think I would want to hear them. If they’re alive, that’s one thing. I have not had the opportunity of hearing someone who was dead come back with their voice. I haven’t had that opportunity and I don’t think I’m interested in it at this point in my life.”

His story

The voice that discussed the merits of call waiting is the same voice that used to call Gross’ home in North Philadelphia and tell her children what name he used to book his room downtown at the Four Seasons.

“He had to stay at a hotel and have an assumed name because when he would come to visit us at the house all the neighbors would see him,” Michelle Smith said. “They would ring the bell and want an autograph and he would come outside and give them autographs. He was gracious in that way. He was coming to see us, but everyone in the neighborhood wanted to see him, too.”

Chamberlain was the uncle who attended LaMont Lewis’ cross-country meets, popped into Olin Chamberlain’s basketball games, and spent time with Gross and her brother when they visited L.A. each summer.

Uncle Dippy was their uncle who just happened to be 7-foot-1. The documentary — which “explores Chamberlain’s cultural impact, focusing on the areas of power, money, race, sex, politics and celebrity”— aims to show people that he was more than a basketball star.

“He’s so much more than just the basketball player and the guy who had a lot of relationships with women,” Ford said. “I think we will unveil a lot of that. I think you’ll feel like you get to know him as a person and how he felt as a human being to be this ginormous man, this iconic figure who was always the center of attention for good or bad.”

Chamberlain’s sister Barbara Lewis invited the filmmakers to her Las Vegas home, which Ford described as a shrine to Chamberlain. It was almost like she had been preparing her whole life for this project, Ford said. Lewis graduated from Overbrook with Chamberlain, who was 14 months older than Lewis and 14 months younger than Gross. The three oldest of 11 siblings were inseparable as kids.

“She’s always wanted to have something like this to honor her brother,” said Lewis’ son, LaMont.

Ford said that every room in Lewis’ home was filled with Chamberlain mementos — ”It’s like there’s a Harlem Globetrotter room, a Kansas Jayhawk room, a Philadelphia Warriors room, a Lakers room,” he said — and she allowed them to use whatever they could find.

Ford and Dillon discovered photos of Chamberlain’s early days in West Philly, news clippings from throughout his career, and old VHS tapes. It seemed as if the only thing they couldn’t find was the tape of the 100-point game — “Because it doesn’t exist,” Dillon said — but they almost pieced together the entire 1957 epic NCAA final against North Carolina.

Every crate was like digging through treasure, perhaps none more important than the sheet of paper they found with Chamberlain’s writing on it. Before his death, Chamberlain outlined how he wanted his life to be portrayed in a movie or documentary.

“It was so trippy,” Ford said. “Because we were already in full production mode and a lot of creative decisions had been made. But when we looked at it, I would say 80 to 90 percent of what he had on that outline is represented in the film.”

The project is almost exactly as Chamberlain dreamed it would be. And they even found a way for him to narrate his story.

“I want people to understand that he was in his own lane,” Olin Chamberlain said. “Literally, if you talk about the Chamberlain sports car he was building. He had no problem being on his own. He didn’t need a group of folks, per se. But he liked who he liked. He spent time with who he wanted to spend time with. He spent time with other folks who thought about other things than just basketball.”