Billy Cunningham goes from playground rat to the Basketball Hall of Fame | Bill Lyon

“I’ll tell you what I thought when I saw that bust,” Cunningham said at the Hall of Fame. “I said, this is like one of those old Western movies, a John Wayne one, where the cowboy rides off into the sunset and there’s a happy ending. That’s how I feel. This is a happy, happy ending.”

This column originally appeared in The Inquirer on May 7, 1986.

SPRINGFIELD, Mass. — Remember? Oh yes, he remembers the very first time he ever touched a basketball. He remembers it the way most of us remember our first kiss, with that misty, dreamy, faraway look, the years rolling back, the memory seductive and beguiling, the imagination always better than the reality.

"For my fifth birthday, I got a ball," he said. "I ran out of the house and right to the nearest hoop. It was outside, on the playground of my grammar school, St. Rose of Lima, three blocks away. I lived there that summer. I can't put my finger on it exactly, but there was just something about the game. I loved it instantly. "

The court was asphalt and cement. There were no nets. You learned to adjust the arc of your shot to compensate for the wind. This was in Brooklyn, on East Eighth, between Avenue D and 18th Avenue.

“I was a playground rat from that day on,” he said, smiling. “I would have been a gym rat, except there was no gym at St. Rose of Lima.”

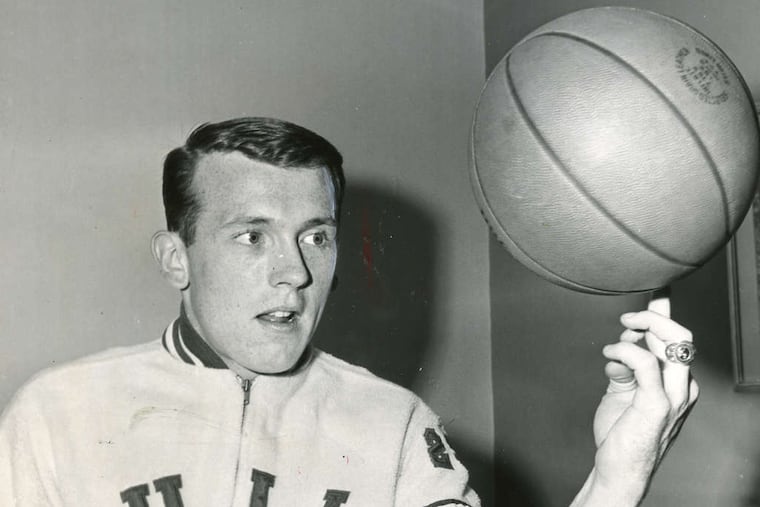

But there would be gyms later on. In a hundred arenas. And now the circle has come full for the playground rat of St. Rose of Lima. The pasty-faced kid who shot lefthanded, who could just naturally jump so high that they called him The Kangaroo Kid, was inducted last night into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Tweet from June 3, 2018:

Like John Wayne in sneakers

Billy Cunningham, one-time Brooklyn playground rat, one-time Erasmus Hall all-city, one-time Kang of the Philadelphia 76ers, one-time Billy C, coach, arrived at the pinnacle of his profession and of his avocation, and found, to his surprise, that his emotions had run a fastbreak on him.

"I never really had gotten very worked up about this," he said. "And then when they unveiled the bust of me, well, it hit me then. "

» FROM THE ARCHIVES: Who’s the greatest coach in Philadelphia sports history?

The nice thing about an honor like this is that you don’t have to be dead to get it. But to be present at the unveiling of a bust of yourself must generate some Twilight Zone feelings.

Billy C laughed.

“I’ll tell you what I thought when I saw that bust,” he said. “I said, this is like one of those old Western movies, a John Wayne one, where the cowboy rides off into the sunset and there’s a happy ending. That’s how I feel. This is a happy, happy ending.”

Well, it is and it isn’t. It is happy, but it isn’t exactly the ending because Billy C is still around basketball. He did commentary and analysis for the college game last winter, and now he is on network TV during the NBA playoffs and the reviews are all raves. He does not belabor the obvious, he eschews the trite and the hackneyed, and he does not mangle the mother tongue. In short, the sisters at St. Rose of Lima should be proud.

“I loved the game from the start, but I was never really very good until my sophomore year in high school,” he remembered. “I started developing physically then. I could always jump. Rebounding was what I did best.”

He was all-city as a junior and senior, and he led Erasmus Hall to the city championship in 1961, his senior year. Even before then, he had made his collegiate choice. Rather, it was made for him.

“Frank McGuire was coaching at North Carolina, and his sister lived right around the block from us. I used to deliver her newspaper. Frank had established the Underground Railroad, getting all those New York kids down to Chapel Hill. My parents told me after my junior year I could either go play ball for Uncle Frank or go to a Catholic university. I wanted to at least visit some of the other schools. I knew I’d go to Carolina, but I wanted the big-shot treatment. But my dad said no, that I might be depriving another kid of a scholarship.”

The script for all of this, you should know, reads just right. Virtue is rewarded. Billy Cunningham’s father and mother were in the audience last night. So, too, was Dean Smith, who ended up being Billy Cunningham’s collegiate coach because, before Billy C ever enrolled at Carolina, Frank McGuire became the coach of the Philadelphia Warriors.

“There was a point-shaving scandal at the time,” Billy C said, “and Dean wasn’t allowed to recruit outside of Carolina. There wasn’t much talent then, so we struggled. But you could tell even then how Dean would turn out as a coach. He was never satisfied; he was always listening, trying to pick up something new. He’s been at the top of his profession for years, and he’s still like that.”

Coming to Philadelphia

The 76ers never saw Billy C play a collegiate game, but they made him their first draft pick anyway, in 1965, on the recommendation of Frank McGuire.

He started his first game as a professional but settled into the role of sixth man. It was a monster team. Wilt Chamberlain at center. Luke Jackson and Chet Walker at forwards. Wali Jones and Hal Greer at guards. The Kangaroo Kid first man in off the bench. That 1966-67 edition has been voted the greatest professional team of all time.

“I don’t know who was the best player ever, but I know who was the most dominant,” Billy C said. "There were so many things about Wilt you took for granted. I mean, it was a given that he’d get you 25 rebounds on just an average night. A player gets 25 rebounds now, and people go berserk. Here was a guy who averaged 50 points a game and couldn’t shoot free throws. Although, it’s strange, but in practice Wilt was a good foul shooter. It was all psychological.

"The year that they said he couldn’t pass, he set out to lead the league in assists, which he ended up doing. But I remember Sports Illustrated ran a piece saying the reason Wilt was passing so much was because he couldn’t score anymore. So he went on a rampage, averaged over 60 for about 10 games just to prove his point, and then he went back to concentrating on assists. He had fallen behind by then, but he caught up in a hurry. "

The Kangaroo Kid got caught in the middle of the war between the NBA and the ABA, and the courts finally decided that if he was to continue to play basketball for a living, it could only be as a Carolina Cougar. He was only gone from Philadelphia for a couple of seasons, but it was a most opportune time to be gone. One of those seasons was the infamous 9-and-73 debacle.

An ‘easy’ ending

Surprisingly, the fans of Philly welcomed him back eagerly, not as some sort of traitor. They had embraced him as one of their own from the beginning, enamored by the way he threw his body wildly about. And then his playing career came to an end without the slightest warning.

“We were playing the Knicks in the Spectrum, and I got a defensive rebound and went all the way to our free-throw circle and my knee just exploded,” he said. “I remember I went down like I’d been shot. People tell me I screamed, but I don’t remember that. It was like I had blacked out. Nobody had touched me; they called a foul on Butch Beard, who was about 8 feet away, but they figured they had to whistle someone. I’d never had a bit of knee trouble before.”

The knee was hopelessly shredded.

“In a way that injury made things easy for me,” he said. “I never had to agonize over that decision all athletes face. When is it time to leave? That decision was made for me. Oh, I tried to rehabilitate the knee. I wanted to come back. But it kept popping out. It was trying to tell me, I guess. And I listened.”

He did return to the Sixers, of course. As their coach. For eight years. And a championship. He was the quickest coach in NBA history to record 200 wins, 300 wins, 400 wins. He probably would have been the quickest to 500, too, and maybe 600 and 700, if he had stayed and if he had been able to retain his sanity.

"That last part, that's the key," he said. "All I know is, since I got out of coaching, I feel younger than I have in years."

He was consumed by the game. As a player, he was a savage, relentless competitor. And he coached the same way. A ravaged knee kept him from staying too long as a player, and his knowledge of the depths of his passion got him out as a coach before he went over the edge.

So Billy C came to the podium last night having achieved about all that is worthwhile striving for in the game: championship rings as player and coach, his number retired and hanging from the Spectrum rafters, some of his stats still in the record books, and now the Hall of Fame.

"I wrestled with what I want to say," he said. "Three or four times I tried to put how I felt on paper, and I found myself going in all directions. My parents are both here, my brother, my sister, my wife, our daughters, all the people who are there for you when you need to reach out, they are here this evening. So I think this is more an award for them. "

On this night, on his night, Billy C chose not to shoot, preferring to pass off instead.