North Philly’s Boathouse Sports, run by a former Olympic rower, switches gears to make masks and other coronavirus PPE | Mike Jensen

“We just wanted to do the right thing. Number one, to help with the COVID crisis. The [PPE] supply chain was empty. ... Some huge companies are getting involved, but some of the hospitals needed it immediately.”

It wasn’t too long before he died when John B. Kelly Jr. — Boathouse Row legend, Kelly Drive named in his honor — saw this guy John Strotbeck, soon to be an Olympic rower, as Kelly had been.

“You’re not very big,’’ Kelly told Strotbeck, as Strotbeck remembers it. “But you sure do know how to move a boat.”

At 6-foot-2, Strotbeck wasn’t big at all by world-class rowing standards. Just big enough to make it to the 1984 Olympics final in the pair, and Strotbeck later rowed in the 1988 Olympics.

“I think that’s because I grew up on the ocean,’’ Strotbeck remembers responding to Kelly about his boat-moving abilities. “I had endurance.”

Growing up in Margate, attending Atlantic City High, Strotbeck had been a lifeguard in the summer, his rowing stroke adapted to rough waters. Which brings us to today, to the rough seas of a coronavirus pandemic, which shut down life as most know it, including the prosperous local sports-apparel business Strotbeck had built over decades, which was suddenly deemed nonessential.

“We were shut down,’’ Strotbeck said of his Boathouse Sports operation, run out of Hunting Park Avenue. “Had to furlough everybody, including myself. About 200 people.”

The following week, Strotbeck was talking to a couple of friends who are nurses in New York. He can’t remember which one mentioned the urgent need for masks and other personal protective equipment. A light went on. Hospitals had surgical filters and wraps, he was told, that weren’t being used for elective surgeries. He had a factory full of sewing equipment.

“We got a few samples,’’ Strotbeck said, and he sent them to the big local hospital systems. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia got back to him right away. “They basically approved them that same day. We made them into masks.”

They delivered their first pallet two weeks ago, and began a project to make surgical gowns.

“Jockey International flew 10 machines into our facility,’’ Strotbeck said, explaining that project was beginning this week, “with an objective of making 50,000 a week.”

It’s all being done “a little above cost,’’ Strotbeck said. “When we started, we just wanted to do the right thing. Number one, to help with the COVID crisis. The [PPE} supply chain was empty. It will fill up pretty quickly, but it’s going to take weeks. It was a just-in-time pipeline. Some huge companies are getting involved, but some of the hospitals needed it immediately.”

The other goal, Strotbeck said, was obviously to get his people back to work.

“Honestly, Boathouse wants to be here in the long run,’’ Strotbeck said. “We’ve been doing this for 30 years.”

» FAQ: Your coronavirus questions, answered

Sports jackets are a big seller. Rowers along the Schuylkill, but also the NFL and other sports. Those jackets Andy Reid wears on cold Sundays on the sidelines? Boathouse makes them, Strotbeck noted. Reid had three green ones and three black when he was with the Eagles. Now, it’s three red and three black with the Chiefs.

“We might have 150 people in our plant, our factory,’’ Strotbeck said. “Of that, maybe 100 are sewers. Yesterday, we had 30 sewers, five supporters. A little over 30% of our normal staff.”

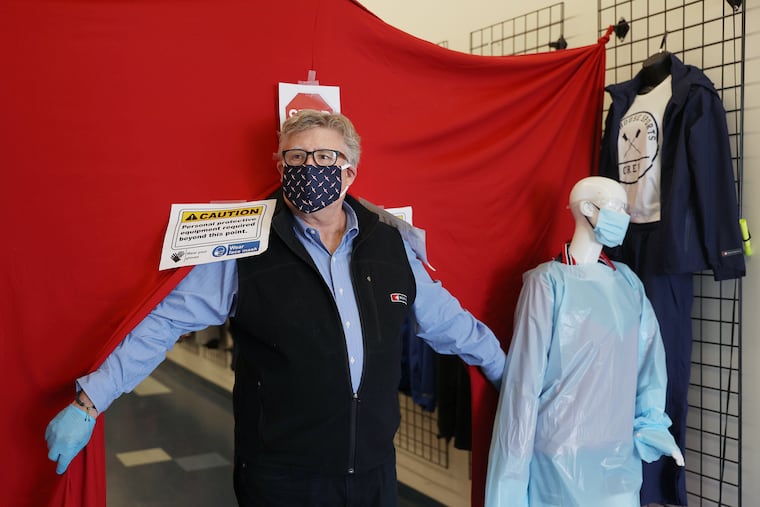

There are tricky aspects, Strotbeck said. “One is the fear of getting sick. We’re doing everything we can. About as good a social distancing space as possible. You’re given six masks, six pairs of gloves when you come in. You go to your workstation only, except for a break for lunch.”

When an Inquirer photographer and videographer were let in Tuesday, lunch break meant one person at a table eating, while a woman used Lysol to disinfect all the sewing workstations.

“We have very good ventilation anyway, but we’ve kind of turned it up,’’ Strotbeck said.

The other issue is some confusion whether an average sewer, making roughly $500 a week, can get more money from unemployment based on the stimulus package right now.

“You can’t fault somebody if they can get $825,’’ Strotbeck said. “Right away we decided to increase pay to our employees just to get them in.”

That’s still a challenge. An executive vice president of operations was sewing masks earlier this week. Strotbeck was learning to package orders for shipping. Wawa had just ordered 50,000 cloth masks for workers, Strotbeck said, so Wawa’s goose logo was going on the fabric.

» READ MORE: Phillies join other MLB teams in participating in massive COVID-19 antibody study

They were working on disposable medical gowns but waiting on the prototype to be approved by a hospital before ramping up production.

The Schuylkill is closed for rowers right now, but Strotbeck still gets out there. After rowing his competitive stroke in Seoul, South Korea, at the 1988 Olympics, Strotbeck basically took the next 21 years off before returning to some good-natured competition.

“I still row,’’ Strotbeck said. “I will admit that I am no longer 6-foot-2, 188 pounds.”

He’s kept his hand in the sport that got him started. He was an assistant at St. Joseph’s Prep for several years, took a year off when he had both knees replaced, but he was supposed to be helping this spring at La Salle High after new head coach Mike Brown switched over from Merion Mercy.

“We had a decent boat that I think could have been a fast boat,’’ Strotbeck said of the La Salle varsity eight. “But we’ll never know.”

» READ MORE: The factory that makes the Phillies’ uniforms reopened to make free masks and gowns to fight coronavirus

The Prep-La Salle rivalry didn’t impact him, Strotbeck jokes, being from the Shore. Plus, business is business.

“We pretty much outfit every sport,’’ Strotbeck said. “Who knew colleges had Quidditch teams? They do.”

Right now, all that is set aside. Boathouse’s business is fighting this virus. Revenue at full production might only be about 30% of what was coming in previously, Strotbeck said, but that’s better than being shut down. His life has been filled, he said, with people telling him what’s not possible. He’s just doing his part right now, pulling an oar as part of a much larger effort.

“It’s right in front of us,’’ Strotbeck said. “How can you not do it?”