Matt Klentak wasn’t the problem with the Phillies; the Phillies are the problem with the Phillies | David Murphy

There are two types of teams in baseball: championship organizations, and organizations that luck into championships. From Cliff Lee to Andy MacPhail, we know where the Phillies stand.

Everything I need to know about the Phillies' chances in the post-Klentak era, I learned on Dec. 16, 2009. Some will remember it as the day they acquired Roy Halladay. To me, it will always be known as the day they traded Cliff Lee.

Forget the trade itself. Everyone knows how that ledger reads. The Phillies gave up one of the best four or five starting pitchers in the game and got future MLB washouts Phillippe Aumont and J.C. Ramirez and a guy who would go on to become the first prospect in organization history to leave his plastic bag of cocaine in the backseat floor of a police car in which he was being given a lift. At best, the deal was disastrous. At worst, it set off a slow, unwitting slide into nuclear winter.

Yet bad trades happen. Even good organizations make them. Where the Phillies revealed themselves to be almost singularly not good was in the decision-making processes that led to the trade. On the day they introduced Halladay to the media, then-general manager Ruben Amaro Jr.'s explanation of the Lee trade was essentially, “Hey, look over there, it’s Roy Halladay.”

And what could he say? While the Phillies were understandably concerned about trading away three of their best prospects for Halladay, it seemed laughably obvious that there are better ways to address that problem than trading away a Cy Young Award winner who earns less than half the salary of the guy you just traded for and is a year younger than him. And if you do somehow arrive at the conclusion that trading such a player is a sensible move, you don’t rush to make it coincide with a more popular and sensible move so that nobody notices. At least, you don’t do these things if you view yourself as a championship organization and understand how such a thing must operate in order to sustain success in the sport’s current competitive environment.

» READ MORE: Mike Arbuckle: Cherry Hill native J.J. Picollo is a perfect fit for Phillies’ GM job | Bob Brookover

A decade later, is it any wonder that the Phillies have yet to get back to the place that they were when Lee was casually making one-handed basket catches of infield pop-ups while dominating opposing hitters as the unquestioned ace of one of the last two baseball teams standing? In baseball, there are championship organizations, and there are organizations that occasionally luck into championships. If the 28 years between 1980 and 2008 were not a big enough hint, and the next 11 years did not erase all doubt, the current front-office boondoggle establishes once and for all where the Phillies stand.

If you think the next general manager will have any more success than the previous two, you haven’t been paying attention. You can argue whether a championship organization would have let Jayson Werth walk without any plans to replace him. Or, if it would have given an aging slugger five years and $125 million as a reward for past performance. It’s much harder to argue that any championship organization can go entire decades without hitting on a first-round pick. But what they absolutely, indisputably do not do is make decisions in the manner that the Phillies consistently make them.

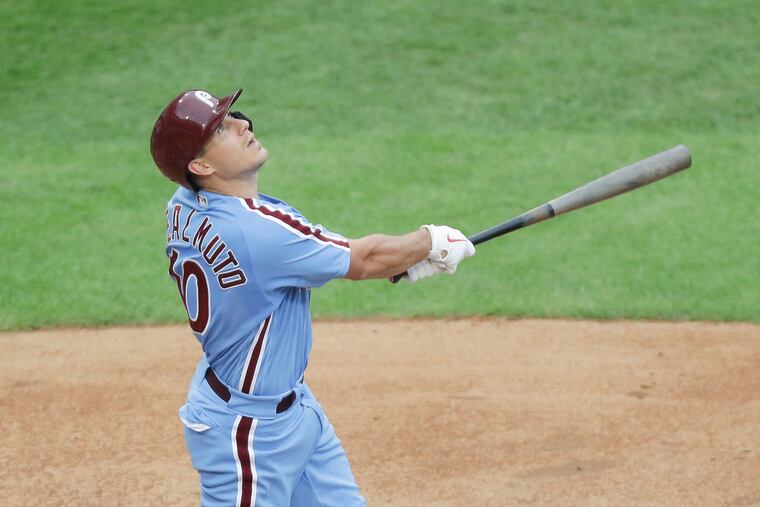

Look at three of the Phillies' most recent franchise-defining personnel decisions and see if you can spot a common thread. In 2015, the team’s majority owner announced that he had decided the Phillies needed to refashion themselves as a modern baseball organization and then announced that they were coaxing 62-year-old Andy MacPhail out of retirement to do it. A few months later, they decided that making such a transition would require them to fire their general manager. One year after that, the team’s majority owner gave the team president’s new handpicked general manager the freedom to replace a well-liked manager with a controversial candidate who had never done the job. Two years later, the majority owner insisted that his general manager fire the guy. Less than a year after that, as the team’s majority owner was personally involving himself in negotiations with Bryce Harper on what would end up being a record contract, the Phillies traded their top pitching prospect for a catcher who was among Harper’s personal favorites. Less than two years later, the majority owner publicly expressed regret over the deal, saying that it should have come with a Realmuto contract extension.

Now, here we are, October of 2020. The general manager has been demoted and replaced by a guy who has been alongside him virtually every step of the way. As with virtually every move that the Phillies have made since John Middleton’s emergence as a hands-on owner, this one looks like the result of a crowd-sourced Choose Your Own Adventure. Instead of scouring the earth for the next Andrew Friedman or Jed Hoyer, the Phillies have decided to swap out some titles and rearrange some desks as MacPhail shoots off some faxes to his network.

The Phillies don’t need Jim Hendry, or Dave Dombrowski, or anybody who makes someone like MacPhail feel comfortable. They need to interview everybody who works for the Dodgers, Rays, and Cubs, and find someone who can build a replica.

But, then, needs are relative things, often mistaken for wants. Understanding that difference is the first of many steps the Phillies must take to become a winner. Unfortunately for the fan base, it’s also the step that seems the hardest.