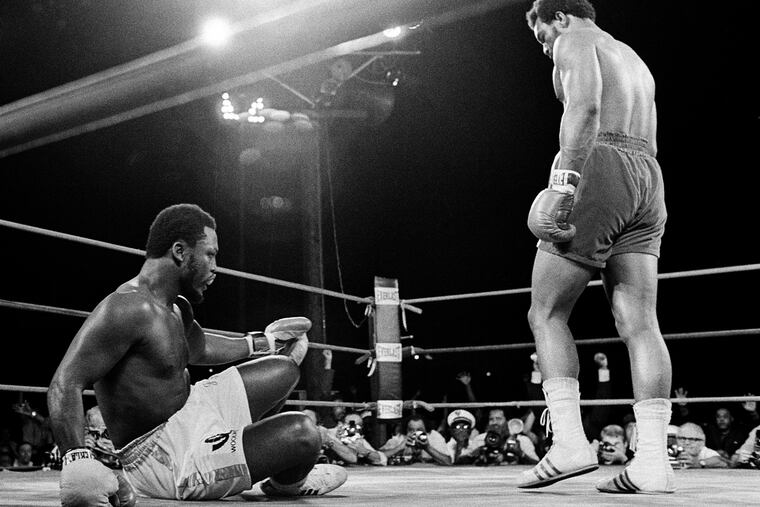

Down went Joe Frazier 50 years ago in a loss to George Foreman that altered lives. Philly would rise again.

The underdog Foreman floored Philadelphia's heavyweight champ six times on Jan. 22, 1973. Even Howard Cosell was stunned.

Fifty years later, Weatta Frazier Collins still remembered. Joe Frazier’s daughter was brought over with her mother to see her father at the hotel in Kingston, Jamaica, later that Monday night, Jan. 22, 1973. He looked like a monster. His eyes were swollen, blotched slits. The sides of his head were lumped up and misshapen.

Joe nodded to his daughter and reassured her that he was OK. Then Weatta came up and hugged her father around the neck, kissing him on his bruised cheek.

The nightmare was over. It didn’t last long — 5 minutes, 26 seconds to be exact.

That’s how long it took George Foreman to wrest the heavyweight championship from Frazier, knocking him down six times in two rounds.

It will forever be marked by:

Down goes Frazier!

Down goes Frazier!

Down goes Frazier!

Three words said three times by an icon, on an iconic day in a fight between two icons that still resonates 50 years later.

Three words said three times that very easily could have been … Down goes Philly! Down goes Philly! Down goes Philly!

It was that bad.

The late Smokin’ Joe was the last standard bearer of Philadelphia sports back then, when boxing was relevant and most sports fans knew who the heavyweight champion of the world was.

Philadelphia pro sports was in a dark, dank auditorium.

Hard times

The 1972-73 Sixers were in the throes of their infamous 9-73 season. The Phillies finished last in the National League East in 1972 at 59-97 despite Hall of Fame pitcher Steve Carlton going a remarkable 27-10. The Eagles were coming off arguably their worst season in franchise history, going 2-11-1 and scoring 12 touchdowns the entire year. The Flyers were just emerging as the saviors of the city in finishing 37-30-11 that season.

» READ MORE: The summer of Super Steve still sticks to the soul of this fan who saw greatness up close

The cumulative record of the four major sports franchises was 107-211-12 in 330 games — a .342 winning percentage.

Smokin’ Joe demanded attention everywhere he went. He was recognized internationally, although he carried a welcoming demeanor to anyone who approached him.

He was also quintessential Philadelphia. He was a grinding, working-class fighter who burrowed into his opponents, punched raw meat in freezers, and was the only one who Philadelphia sports fans could hang their hat on at that time.

Even if you weren’t a boxing fan, you were a Joe Frazier fan. He was all Philly had.

After Frazier arrived back in Philadelphia after winning the 1964 Olympic gold medal in Tokyo, the Eagles honored him with a victory lap in a convertible on the track at Franklin Field and the applause he drew was deafening.

» READ MORE: Joe Frazier celebrated at funeral

In 1973, 27-year-old Ray Didinger was covering the Eagles for the Philadelphia Bulletin. He remembers watching the Frazier-Foreman fight live and was as surprised as everyone else when Frazier lost. At the time, Frazier was 29–0, with 25 knockouts and 10 title defenses. Foreman was a 3½-to-1 underdog who had not fought anyone of note, building a 37-0 record, with 34 knockouts.

Joe was also 5-foot-11 ½ with a stubby 73-inch reach compared to the 6-3 Foreman’s 78½-inch reach.

Still, the 1968 Olympic gold medalist had his detractors.

“I thought George was never in with someone like Joe, and I thought Joe would be too much for him, and I remember thinking the outcome was too stunning to me,” recalled Didinger, 76. “I remember covering Joe’s fight against Terry Daniels, while I was covering Super Bowl VI in New Orleans. I remember how frightening it was when Joe caught Daniels in the rib cage with a left hook.

“It sounded like an axe chopping wood. I remember Daniels’ legs shook all the way down to the floor. It’s the first time I was ever that close to a fight like that. Seeing how ferocious Joe was, and how powerful he was, I thought Joe was going to be heavyweight champion for a long time, with the image of the Daniels fight in my mind.

“Joe was the light in the darkness of Philadelphia sports back then. He was a scrappy guy who took down Muhammad Ali.”

That’s what Foreman thought.

“There was no way I was supposed to win that fight,” said Foreman, 74, whom more millennials may know for the millions he made with the George Foreman Grill than as a Hall of Fame fighter who was the two-time heavyweight champion. “I was afraid of the man. Joe was a giant slayer. I looked into that man’s eyes and I saw a beast.

“I was supposed to be part of Joe’s ‘Bum of the Month’ tour until he could get back with the big prize and fight Ali again. I got in the way. No one expected me to beat Joe, and after I did, I became a giant slayer George,” Foreman laughed.

» READ MORE: This new Philadelphia mural honors boxing legend Joe Frazier

Foreman was Mike Tyson before Mike Tyson — against far greater opposition. Frazier was tailor-made for Foreman. He would come at Foreman, which “Big George” welcomed. Foreman’s tactics were to push Frazier off of him, creating a distance to get the full impact of his punches.

‘Howard went crazy’

Foreman watches a replay of the fight often.

Howard Cosell, the seminal ABC sportscaster, had his doubts, too. He thought Foreman had a shot at beating Frazier, though when Frazier went down the first time, Cosell, like everyone else in Kingston’s National Stadium, was shocked.

“It’s why Howard went crazy,” Foreman said. “I stood my ground and I turned my right into a right uppercut and Joe bent right into it. Joe didn’t realize how many fights I had. I knocked everyone out I fought.

“Frazier was a phenomenon. I was someone who ‘never fought anyone.’ I saw a tiger when I looked in that man’s eyes. I was never afraid of anyone in my life. That man was a piece of steel. I was afraid of Joe.”

Cosell did not know what he started, nor how long his simple three words said three times would endure.

You might hear someone utter it in a grocery store when a milk carton is dropped. It has been turned into a popular meme, and most born after 1990 have no idea where it originated.

In Philadelphia, Frazier losing was big news. It was lost everywhere else. Jan. 22, 1973, was an iconic day in American history. It was the day former U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson died of a heart attack in Texas at 64. It was the same day the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Roe v. Wade, and when Henry Kissinger flew to Paris in a bid to end the Vietnam War.

Foreman’s team kept the news of LBJ’s death from Foreman. That was their order: Keep him secluded. Foreman had enough in facing Frazier. LBJ started the Job Corps, which changed Foreman’s life. He was a brooding, stoic high school dropout who found a path through boxing.

“Through the Job Corps, I was introduced to boxing,” Foreman said. “I met LBJ once after I won the [1968 Olympic] gold medal and again when he invited me back to a state dinner.

“What a day that was. I became heavyweight champion, but no one wanted me to know [about LBJ’s death], because my people thought it would affect me in the ring. I’m happy that they did. My gracious, there will never be a day like that again. Jan. 22, 1973, changed my life.”

Foreman was carried out of the ring on his back after the victory.

The aftereffects

Frazier fought Foreman again three years later and lasted five rounds before being stopped again. Frazier never won the heavyweight championship again. The loss was a dagger to the Frazier family’s collective soul. Marvis Frazier, Joe’s son, was ringside in Kingston. He grabbed the crummy canvas and yelled to his father a few feet away, “Daddy get up, stop playing!”

“Yank Durham, my dad’s trainer, wanted none of those fights with George, I can tell you that,” Weatta Frazier Collins said. “My dad would fight anybody. He did the work and once he did, he thought he could beat anyone. I don’t watch daddy’s fights. It hurts too much.

“It’s something I was never able to do, even the fight he beat Ali. Our family loves George. My daddy left a great legacy. My daddy went through great pain. All of that punishment, all of those punches he took, went for a greater good for his family and the education and opportunities we all received. My husband and I recently were talking about Tom Brady, and I remember telling my husband, once you’re on top, you always want to be on top. I don’t blame Tom Brady for continuing to play.

“You have the attitude of being the best, ‘the world needs me.’ If you leave that life, depression sets in with these individuals. Tom Brady doesn’t want to go back to what is really normal. My daddy went through some of that. These individuals are special. They’re not normal. My father was in that same boat. Daddy wanted to continue. And then after he lost, he wasn’t.

“I’ll always remember going up and hugging and kissing my daddy on the cheek after the loss to Foreman.”

Foreman, ironically, forged forward with many Philadelphia ties. He lost to a Philly fighter, slick Jimmy Young, who ended his first ring incarnation. Ten years later, Foreman came back and shocked the world again when at 45 he knocked out Michael Moorer on Nov. 5, 1994, to become the oldest fighter to win a heavyweight title. His age-longevity record was later snapped by yet another Philadelphia fighter, Hall of Famer and all-time middleweight great Bernard Hopkins.

» READ MORE: Bernard Hopkins’ Hall of Fame career started with a visit in prison from a boxing ref named Rudy Battle

In 1974, the Flyers won the first of their two Stanley Cups, a bunch of Joe Fraziers on skates. Three years after the fight, the 76ers acquired Julius “Dr. J” Erving, changing the course of that organization, the Eagles hired a young, energetic coach from UCLA named Dick Vermeil, and a young core of Phillies matured to win 101 games and made the postseason for the first time since winning the 1950 National League pennant.

The 50th anniversary of “Down goes Frazier” falls on this Sunday. Foreman will get up around 6 a.m. He’ll take the 30-minute drive to the Church of the Lord Jesus Christ in Houston. Afterward, the congregation will go over to the church house next door and have cake.

He’s planning on writing a sermon commemorating Jan. 22, 1973, the day that altered more than a few lives.

» READ MORE: Frazier-Ali statue unveiled on 50th anniversary of the ‘Fight of the Century’

“Joe has a strong legacy here in Philadelphia, I fully believe that,” Didinger said. “You don’t need to be well-schooled in boxing history to know who Frazier was. More importantly, understand where he came from and what he stood for. That image of Frazier aligns with Philadelphia and its own self-image. If Ali had been a Philadelphian (and lived in Cherry Hill for a brief time), he would have been great, and would have had a statue, but it would not have been quite the same.

“His personality and his backstory would not have been as much a fit for Philadelphia and Philadelphia’s own self-image as Joe Frazier’s history was. He was Philly with a left hook.”

Joe Frazier died of cancer in 2011. A week after being interviewed for this story, Weatta Frazier Collins passed away.