Mitchell & Ness is a global brand. Forty years ago, the Philly company was nearly bankrupt.

Peter Capolino, who created the throwback jersey, once hid from creditors. But the second and third floor near 13th and Walnut proved to be more than a good hiding spot.

The second and third floors of the old building near 13th and Walnut Streets held the world’s largest collection of backdated periodicals, making it an ideal place to pass some time. Bookcases lined the floor and the stacks of old magazines nearly touched the ceilings. Sports Illustrated, Life, Look, The Sporting News, Time, and even Playboy. David Bagelman’s collection had them all.

For Peter Capolino, the stacks provided the perfect hiding spot 40 years ago when the creditors arrived downstairs at his nearly bankrupt sporting goods store. Capolino took over Mitchell & Ness from his father in 1975. By 1983, it was drowning in debt.

He let go of all but two employees, downsized to a storefront below Bagelman’s Reedmor Books, and tried to steady the ship. Capolino did not want Mitchell & Ness to close as the company — now an iconic sports brand worth nearly $250 million — had a history in Philadelphia and gave his father, Sisto, a place to live when he was an orphan after immigrating from Italy.

So when the bankers came looking for their money, Capolino went upstairs.

“I would go up and breeze through those magazines,” said Capolino, 78. “They would just tell the creditors ‘He’s not here. We’ll have him call you back.’”

How it started

Mitchell & Ness sold in February 2022 for $215 million as the company is the king of throwback sports apparel. It sells jerseys of every player from Babe Ruth to LeBron James and is licensed by every major sports league. But it didn’t always sell throwbacks.

The company formed in 1904 when Pete Mitchell and Charles Ness joined together to open a store in Center City that specialized in tennis and golf equipment. Mitchell strung tennis rackets while Ness made golf clubs.

That same year, Sisto Capolino was born in a coastal Italian fishing village named Formia between Rome and Naples. In 1917, Capolino left on a boat with his parents to flee from a cholera epidemic that was ravaging the country. His mother died on the ship and his father died shortly after arriving in Philadelphia.

» READ MORE: Why one of college baseball’s top hitters plays with Jackie Robinson’s No. 42 tattooed on his arm

Capolino didn’t speak much English, but Mitchell and Ness hired him to sweep their shop. He was soon living in an apartment upstairs and managing the store after earning his high school diploma at night. In 1952, Capolino purchased the store.

The company sold everything from vaulting poles and skis to hockey sticks and table tennis paddles. Mitchell & Ness outfitted the Phillies, Athletics and even the schools in the Inter-Ac League. It was the first Philadelphia store to sell Adidas, and Phil Knight — who founded Nike — used to call the shop when he was selling for another shoe company.

Mitchell & Ness never handled the 76ers or Warriors, but it supplied everything for the Eagles — from their helmets to their shoes — from 1933 to 1963.

“I helped put on the face masks before the 1960 championship game,” said Capolino, who was 15 years old when the Eagles topped Vince Lombardi’s Packers at Franklin Field.

Birth of throwbacks

Capolino — who went to Susquehanna University after graduating from Yeadon High School in Delaware County — took over the company in 1975 when his father had cancer. No longer outfitting the pros, Mitchell & Ness struggled to find its footing in a changing industry. That’s why the creditors were downstairs and the stacks seemed to be closing in.

“I got us into high-volume, low-profit margin business,” Capolino said. “I went to college and studied philosophy and sociology because I never expected to work for my father. Here I am, I have no idea what I’m doing. I’m buying all this stuff, borrowing all this money at the prime rate, selling stuff at an almost lower profit margin than the interest he was paying to the bank. It all caught up to me.”

Capolino didn’t know what the future of Mitchell & Ness looked like, but he knew he had to keep the business churning. And then a man walked into the store in 1984 with two old baseball jerseys. He asked Capolino if he could repair them.

The tops — one from the Pittsburgh Pirates and another from the St. Louis Browns — were made of wool and Capolino knew of a mill on North Broad Street that had thousands of yards of extra fabric. Yes, he could do it. The customer told him to be careful with the jerseys as they were worth a lot of money.

“I said, ‘Really?’” Capolino said.

That’s when an idea — the one that could save the business that provided his father with a life in Philadelphia — was born. Capolino asked the customer if he could make six replicas of his jerseys. He would give one to him for free and sell five. The guy did not mind.

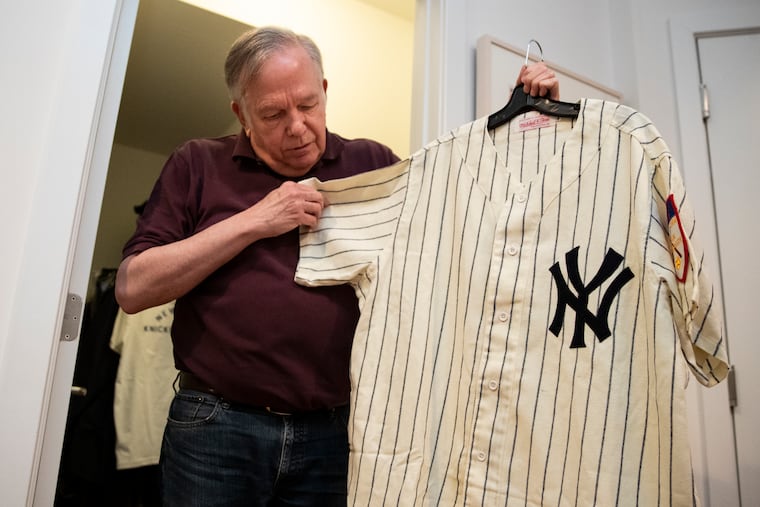

The jerseys sold out instantly. Capolino made more, raised the prices, and watched them sell out again. His customers had never seen anything like it. The throwback jersey was born. It led Capolino back upstairs to those stacks as he paged through old sports magazines searching for photos of the next jerseys he could produce. The place he once hid was now where he went for inspiration.

“I just kept going. I said, ‘I’ll make jerseys until it stops.’ It just never stopped,” Capolino said. “Look at that pinstripe, let’s make some Mickey Mantles. Look at that other pinstripe, let’s make some Richie Ashburns. And look at that white, let’s make some Ted Williamses.”

» READ MORE: Former Eagles star Connor Barwin leaves Wharton with an MBA and a stake in an Italian basketball team

By 1987, Capolino was producing the jerseys of 90 players. Everything was selling. Mitchell & Ness didn’t even have to advertise. An article in Sports Illustrated resulted in 3,000 requests in one week. Capolino opened a phone bank in Utah to handle orders. The business was saved. Major League Baseball sued him in 1988 but then granted him an exclusive license when he arrived at MLB’s Manhattan office with 40 jerseys and showed what he was making.

“What I had tapped into was people’s memories,” Capolino said. “You know how you have a visual memory of something that doesn’t go away? Baseball fans, they have visual memories. I knew if I could make this jersey exactly the way that people remember it and perfectly to the T, it would trigger that memory. That’s what I focused on. Making it so perfectly that it triggered that memory and brought back these warm feelings.”

Hip-hop takeover

By 1993, Mitchell & Ness had an annual revenue of $3 million. The baseball strike in 1994 hurt, but the 1996 World Series — which the Yankees won with a rookie named Derek Jeter — provided a boon in business. The company soon landed deals to produce NBA and NFL jerseys and Capolino’s wife, Fran, urged him to produce MLB jerseys that weren’t wool, which teams stopped wearing in the early 1970s. She reminded him that young people have memories, too. And that’s when the business reached new heights.

OutKast — the Atlanta hip-hop duo — wore Mitchell & Ness jerseys in a 1998 music video and it soon seemed like every rapper was doing the same. Reuben Harley, a customer from West Philly who frequented the store, told Capolino that he could get his products in the hands of more rappers.

Capolino used to watch MTV, VH1, and BET on mute at night while riding his exercise bike just to see who was wearing his jerseys. Capolino didn’t listen to rap, but he became friends with rappers like D.M.C. and Fabolous and even scored a nickname — P. Chatty — from P. Diddy. In 2003, the company had a revenue of $40 million.

“He had a lot of access to a lot of guys who liked him,” Capolino said of Harley, the man popularly known as Big Rube. “The whole thing just kept getting bigger and bigger.”

How big was it? Capolino didn’t rely on marketing surveys to tell him what jerseys to make. He instead just made what he thought was “historically relevant.” That’s why he made one for Sammy Baugh, the Washington quarterback who had seasons when he led the league in passing yards and TDs but also in interceptions as a safety and average punting distance.

“I said, ‘I have to make this jersey,’” Capolino said. “He was this wahoo guy from Texas Christian University. I made a deal with Sammy. He couldn’t believe I wanted to make his jersey. It was a plain maroon jersey, the plainest thing with these funny little No. 33s on the front and back. It’s totally ugly. If you see it, you would never want it. But there was somebody who wanted it.”

» READ MORE: How ‘Here Come the Sixers’ became the hit record three Delaware County friends once dreamed of

That somebody was Jay-Z. He wore the jersey in the 2001 music video for “Girls, Girls, Girls” and then seemed to wear it everywhere he went for the next year. Slingin’ Sammy Baugh’s jersey became the company’s all-time No. 1 seller. Everyone wanted what Jay-Z had. Capolino’s wife would mail the royalty checks to “Sammy Baugh, South of the Mountain, Rotan, Texas.” Baugh had no idea who Jay-Z was.

“He called me one day and he said, ‘Peter,’ in this Texas accent, ‘I have no idea why you’re sending me this money but it’s more than I ever made in the NFL and I just want to thank you,’” Capolino said. “I said ‘Sammy, you’re a legend and you’ll never be forgotten.’ He died in 2008 and had no idea about the real reason that everyone was buying his jersey. Thank you, Jay-Z.”

Moving on

A few years later, Jay-Z rapped in a song that he was done wearing jerseys. The same guy who helped spike business also caused a dip as Capolino said the company’s sales declined a bit when other rappers followed suit. He sold Mitchell & Ness to Adidas in 2007 and stayed with the company until 2012.

It was sold again before a group that includes Bryn Mawr’s Michael Rubin and even Jay-Z purchased it in February 2022. The company’s “flagship store” at 13th and Walnut is less than a block from where Capolino used to hide and “Philadelphia” is still printed on the tags of jerseys.

Capolino has not been contacted by the new owners. And that’s OK, he said. He has no financial interest in the company but still feels a connection to Mitchell & Ness. The company that gave his father a chance is the one he saved.

There was some luck — Capolino tried to sell his house in 1980 and open a tennis shop in Newtown, but the house failed to sell — but there was also some ingenuity to realize he could make the pictures in those old magazines come to life. The second and third floors at 13th and Walnut proved to be more than just a good hiding spot.

“It was just an amazing ride. It’s funny, the life turns that you take,” Capolino said. “Some of them are total serendipity. Some of them are good luck. I’ve had these things happen to me. I always say my father can stop rolling over in his grave. Mitchell & Ness is going to be fine way past our deaths. I look at it like it’s a miracle. I was very lucky.”