Three Philadelphia athletes felt the ripples of evil from the massacre at the 1972 Munich Olympics

As security comes into focus for this year's Paris Games, here's a look at how three area Olympians learned about and coped with the terrorist siege against the Israeli team.

It is impossible, as the Summer Olympics in Paris draw closer, to escape the unease that the world is a single struck match away from an inferno … and that the Games themselves could be kindling.

France has trumpeted the promise of an unfettered and “dreamlike” setting for these Olympics, adopting the slogan “Games Wide Open!” But the sheer number of security officials — a reported 85,000 among police officers, private contractors, and military — who will be patrolling Paris and its halo communities is a testament to the ever-present caution and worry. Incidents of antisemitism have skyrocketed globally since the Oct. 7 attacks in Israel. The war between Russia and Ukraine rages on. The opening ceremonies, featuring a boat parade along the Seine River, will commence inside what the city’s police chief has called an “anti-terrorism perimeter.” Military helicopters will fly overhead. Breath will be held.

“They are scared out of their minds,” said a U.S. national-security expert who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “There is deep concern over bad things happening. It’s the stage. It’s fertile ground to find somebody who wants to do something to give meaning to their lives.”

That context and those conditions aren’t so different from those that surrounded another Olympics. The darkest Olympics. The Olympics of Munich 1972.

Just after 4 a.m. on Sept. 5, eight members of Black September, a radical pro-Palestinian organization, infiltrated the Olympic Village by scaling its walls, shot two members of the Israeli team to death, and took another nine hostage. During a botched rescue attempt at a nearby airport, all nine of those hostages and five of their abductors were killed.

The Games, after a day’s pause, continued.

Three members of the 1972 U.S. Olympic Team, through published recollections and lengthy recent interviews with either them or their families, described their experiences during and perspectives on the atrocity at Munich. Each of them had grown up in or near Philadelphia. Each of them was close enough to the terror to quiver in the aftershock. Each of them, while competing at the event that was supposed to be the pinnacle of their athletic careers, found themselves carried along for a short while on the ripples of evil.

The man on the water

Jim Moroney’s hometown newspaper made him a magazine cover boy when he was just 19 — 6-foot-2 and 190 pounds, blond hair, bare feet, standing on a dock, wearing a white USA T-shirt, a faraway look on his face. In mid-1972, Moroney and his three fellow rowers, all from the city’s Vesper Boat Club, all of whom would represent the United States in the coxless fours at Munich, posed for a promotional photograph, and the editors of The Inquirer’s TV Week insert splashed it on the cover of the Aug. 27-Sept. 2 issue. In the picture, Bill Miller, the second rower from the right, wields an oar across his chest as if it were a medieval weapon. The young men appear poised to conquer the world.

A Merion native, Moroney had no such lofty aspirations until his sophomore year at St. Joseph’s Prep. An injury prevented him from playing football, and Mike Vespoli, a math teacher at the Prep and its rowing coach, started bugging him to try rowing, knowing that Moroney had several friends already on the team. “I remember thinking, ‘This can’t be that tough,’ ” Moroney said by phone recently. Relatively speaking, it wasn’t. He helped the Prep win a junior-four national championship and competed twice at worlds before qualifying for Munich.

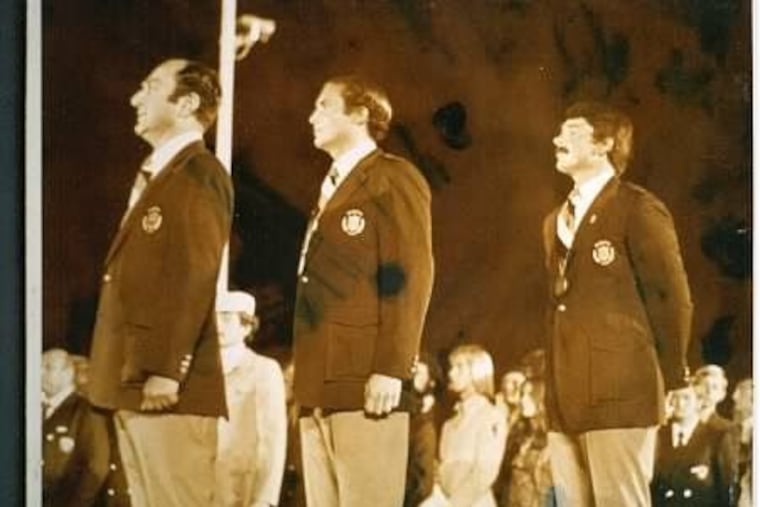

He had entered the Games, held around the time he began his freshman year at Penn, believing that he had nothing to lose in the experience. The spectacle of the opening ceremonies was itself entrancing — 121 nations parading into the Olympic stadium to the sounds of a marching band, the American athletes clad in white jackets, red pants, blue shirt, and white boots — and the coxless fours went off just three days later. But once his boat lost its first race and fell short of the finals, Moroney was devastated. Competing in the Olympics, he recognized, had nowhere near the same meaning that winning at the Olympics would, and he would have to wait four years for another opportunity to achieve that goal.

His consolation was that he could spend the following two weeks commiserating with other athletes either at Munich’s biergartens and town squares or inside the Olympic village, an array of apartments and bungalows similar to a condominium complex, “a very festive environment,” Moroney said. “If somebody had friends and relatives and had passes to get into the village, you could just kind of fake it, and they would let you in.”

Nothing about the environment was festive when Moroney woke for breakfast on the morning of Sept. 5. From the balcony of his eighth-floor room, he could see another apartment tower in the village cordoned off with security tape and surrounded by police and military. What’s going on here? he thought.

He wandered down. Black September held the Israelis captive on the second floor. Moroney fell in with a crowd of athletes who had gathered within 50 yards of the building, and whenever the terrorists showed themselves — as one, his face cloaked by a ski mask, did in the most memorable image from the atrocity — the crowd jeered and swore at them. Moroney stayed quiet and didn’t stay long.

“I was young, but I wasn’t stupid,” he said. “I was thinking, ‘These people are crazy. This isn’t a good place to be.’ Not that they would have opened fire, but you never know. Nothing was normal.”

He returned to his apartment. Some of the rowers had cameras with telephoto lenses. They leaned over the ledge and snapped photos. A couple of nights later, Moroney and several other athletes headed to the village’s 24-hour cafeteria for a snack, and they encountered several members of the U.S. rifle team.

» READ MORE: NBC hopes the Olympics’ return to Paris will get fans to return to watching

“I remember one of them saying that they had offered their services to the Germans as snipers,” said Moroney, who, after winning a gold medal at the 1975 Pan-American Games and rowing at the 1976 Summer Games in Montreal, became the controller for a building-automation company in Andover, Mass. “He said, ‘They turned us down.’ ”

Lanny Bassham, a silver medalist at Munich in the 50-meter Rifle 3 Positions, denied that he himself had volunteered to assist in any rescue operation. “Could we have done that? Yes,” he said by phone from Flower Mount, Texas, near Dallas. “Were we upset that these terrorists had killed our fellow competitors? Obviously, we were furious. But we felt like that was not our job.”

It’s possible, Bassham acknowledged, that someone else on the team might have bragged, Oh, it would have been an easy shot. Yes, someone might have said something like that, and who knows how Jim Moroney might have interpreted it? People were dying at the Olympic Games. Nothing was normal.

The man in the air

Every morning in Munich, Mike Bantom and his 11 teammates on the U.S. men’s basketball team would wake up, stretch, and saunter down the hall to the room of the team’s trainer, A.C. Gwynne. While waiting their turns to have Gwynne tape them up, some of the players would mingle on the apartment’s terrace. On Sept. 5, a few, the 6-foot-9 Bantom among them, stood on the terrace and looked across the Olympic village at one of the other buildings. They saw armed soldiers outside.

“The first thing we were told was, ‘Somebody got shot last night,’ ” Bantom said in a phone interview. “We were like, ‘What?’ There were no other details.”

Bantom had grown up in a rowhouse at 28th and Somerset before starring at Roman Catholic High School and, as a junior at St. Joseph’s University during the 1971-72 college basketball season, establishing himself as one of the most dynamic forwards in the nation. Described by one writer as “a runaway pogo stick” for his leaping ability, he averaged nearly 22 points and 15 rebounds for a Hawks team that, under coach Jack McKinney, went 19-9.

Throughout the spring and summer of ‘72, Philadelphia was so dangerous that one newspaper in town published a banner across the top of its front page each day with the updated number of children and teenagers who had died in gang-related incidents. So Bantom’s selection to the Olympic team was, in his mind, a stroke of good fortune. He was relieved that he had been removed from that threatening environment, and he couldn’t fathom the notion that anything other than a neighborhood turf battle might inspire the kind of violence that apparently had bloodied the Games.

“Being from North Philadelphia, I assumed it was a personal thing,” said Bantom, who went on to play nine years in the NBA and work as a league executive for more than 30 years. “Somebody was in a fight. Something happened. I didn’t think of the magnitude.”

Stacked with talent — Doug Collins, Tom Burleson, Tom McMillen, Dwight Jones — and having routed Japan by 66 points two days earlier in the preliminary round, the U.S. team was scheduled to hold two practices on Sept. 5. A bus would shuttle the coaches and players to and from a gym at a nearby army base; there, they could work out in private, once in the morning and once in the early evening. This time, though, instead of shepherding the team back to the village to rest after the first practice, the bus stayed at the base. The players lounged around the gym with nothing to do until they practiced again at 5 p.m. Only then did the bus transport them back to the complex.

Less than four decades after Hitler had tried to assert the Nazis’ supposed racial superiority at the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin, less than three decades after World War II and the Holocaust had ended, West German officials had billed the ‘72 Summer Olympics as “radiant” and “cheerful.” They were desperate to downplay the country’s history of totalitarianism, to avoid any action that fostered even the slightest perception of a police state.

“There’d been no security at all around the village,” Bantom said. “The entrance we always used, especially when we would walk out on foot, was being manned by college-aged students who were volunteers. They just checked your ID as you walked by. That’s part of why those people could come in at night and do what they did.”

Now, the U.S. team bus trundled toward an entrance to the Olympic complex, and security, for the first time, stopped it. As the vehicle idled and the players sat within, Bantom noticed two dark helicopters rising out of the village, their blades thumping overhead.

“Once that happened,” he said, “they let us all back in.”

» READ MORE: Remembering the terrorist attack at the 1972 Olympics in Munich

In their rooms, where their televisions broadcast news reports only in German, the players began calling family members back home to find out what exactly was going on. The helicopters that Bantom had seen were a pair of Bell UH-1s, military machines, and they were transferring the remaining hostages to Furstenfeldbruck Air Base, where Black September planned to fly them to Cairo … and where West German police planned an ambush to free the Israelis. At Furstenfeldbruck, the hostages died amid chaotic gunfire and the detonation of a fragmentation grenade inside one of the helicopters. It was 3:24 a.m. in Munich when Jim McKay, who had been anchoring ABC’s coverage for 14 uninterrupted hours, told the world: “They’re all gone.”

“The first news we got was that they had gotten to the airport, police had intervened, and they had been rescued,” Bantom said. “Then we got the real news: There had been a confrontation, and all these people had been killed. It was crazy.”

The next day, during a memorial service held at the Olympic stadium and attended by 80,000 people — a memorial service for the slain Israeli athletes at which he never mentioned the slain Israeli athletes — Avery Brundage, the chairman of the International Olympic Committee, announced: “The Games will go on.” The U.S. men’s players’ reaction to Brundage’s declaration was unanimous: They wanted to go home.

“We didn’t think, with all these people who had been murdered, that these Games were all that important anymore,” Bantom said. “And we certainly didn’t feel safe being in another country, knowing that it was that easy for someone to come in there and do what they did.”

The team had already advanced to the medal round, however, so the players’ consensus attitude eventually shifted. Let’s just play these last two games and get the hell out of here. By routing Italy, 68-38, in the semifinals, the U.S. men ran their aggregate Olympic record to 63-0. But the gold-medal contest turned out to be maybe the most infamous game ever in U.S. basketball: a disputed 51-50 loss to the Soviet Union that remains controversial and mysterious to this day for the three chances the Russians got to run an inbounds play at the end — the third time led to the winning basket — and the belief among the Americans that the outcome was fixed. They have never accepted their silver medals.

Imagine if Bantom and his teammates had followed through on their initial reluctance to play because of the massacre. Imagine how different history might have been.

“It weighed on us,” he said. “There was definitely a more somber mood to us after it happened. They were all young people who had nothing to do with what was going on in their country or what was going on in the world, and they paid the price.”

The man on the wind

The only nautical experience that Donald Cohan possessed before becoming a world-class sailor was a couple of outings when he was 8 years old, cruising in a powerboat with his uncle Hy, fond childhood memories that evolved into an obsessive chase for excellence. Cohan was 38, a Mount Airy resident and Cheltenham High School alumnus, and already a powerful Philadelphia attorney when he decided that he would teach himself to sail. His three children, even now, cannot explain why he did.

“He took to water like a duck,” his daughter Susannah Cohan McQuillan said.

In 1968, his first full year of sailing, he tried out for the U.S. Olympic team, finishing in the middle of the fleet. “I swore,” he told the Daily News in August 1972, “four years later, I’d make it.”

Honing his skills at a yacht club on Martha’s Vineyard, Cohan soon piloted a Dragon-class sailboat: with a medium spinnaker and a large mainsail, with two crewmates, one of whom, Charlie Horter, was from Villanova. The three men abstained from alcohol and desserts as part of a rigorous training and exercise program, one necessary to control a 30-foot boat for four hours in the face of 35-mph wind gusts.

“Our father,” Cohan’s daughter Rachel said, “was exceptionally competitive.”

In early 1971, their boat — named Caprice, because Cohan had taken up the sport on a whim — finished fourth at the World Championships in Tasmania, their bid for a medal thwarted when a freak tornado put their teamwork to the test and nearly sank them.

“We were caught with the spinnaker up,” Cohan later said, “but without one word spoken, each of us did what we had to do.”

At a pre-Olympic regatta later that year, his tuning partner — a sailor who agrees to help another prepare for a race — was Juan Carlos, the king of Spain. Gunships tracked them on the water. “Terrorists had threatened to kill the king,” Cohan told The Hartford Courant in 2006. “Now I had this on my head.” When Cohan’s boat won the event, Juan Carlos greeted him with a hug. Then, in July 1972, Cohan and his crew finished first at the Olympic trials on San Francisco Bay to qualify for Munich.

“I’m 42, not a kid,” he said afterward. “I’ve only been in competitive racing for four-and-a-half years. I can’t believe all that’s happened so fast.”

He would be one of two members of the entire U.S team who were Jewish. The other was swimmer Mark Spitz, who in the Games’ first week won a then-record seven gold medals. Cohan would not compete under the same spotlight. The sailing events took place on the Baltic Sea near Kiel, more than 400 miles north of Munich, and the final Dragon-boat race wouldn’t be contested until Friday, Sept. 8. So Cohan split his time between the two cities, befriending the two sailors representing Israel. “They were a lot younger,” Rachel said, “and he would give them pep talks. He took them under his wing.”

Still in Kiel on Sept. 6, unaware of the massacre because he hadn’t bought a newspaper that morning, Cohan traveled back to Munich to meet his wife, Trina, who had flown in for a visit and was staying a mile outside the Olympic village. The sun setting as he walked back to the complex, his vision obscured by the crepuscular sky, he reached a six-foot-high chain link fence that encircled the village. As Cohan scaled and jumped over the fence, two German soldiers — one with a shotgun, one with a pistol — pointed their weapons at him, and two German shepherds barked at his feet.

Cohan threw up his hands and sputtered out what broken German he could: “Ich bin ein athlet.” I am an athlete.

One of the soldiers responded in English. Do you realize how stupid you are? I have orders to shoot anyone who’s trying to break into the village. Don’t you know the Israeli team was slaughtered yesterday?

They let him go.

By the time Cohan and his crewmates reached the final, the Israeli government had extricated the country’s remaining Olympians from Munich, and Spitz had been spirited first to London and then back to the United States.

Brundage’s remarks at the memorial service angered Cohan; 11 innocent men had been killed, and Brundage couldn’t bring himself to utter their names? Before the Israeli sailors left, they approached Cohan and handed him the satin, blue-and-white flag — shaped like a triangle, with the words Sports Federation of Israel, XXth Olympiad Munich 1972 stitched across it — that had flown from their boat.

Before the starting gun of the Dragon-boat final, a West German sailor told Cohan, You’re a sitting duck out here. Whether the comment was intended as pre-race gamesmanship or something more ominous, Cohan never knew.

“I think he took it as both a threat and an observation,” his son Ben said. “You could shoot anyone on the water. It was that kind of milieu or environment.”

The race went off without any unusual occurrence. Caprice and its crew made a late charge to finish third in the event. No Jewish athlete had ever won an Olympic medal in sailing before Donald Cohan won the bronze. Over his full career, he won two Pacific Coast championships and 14 Atlantic Coast championships, and represented the U.S. in the world championships 14 times.

“If the Games were to go on and the IOC wouldn’t acknowledge the magnitude of the tragedy,” he once said, “I would. By winning.”

He died, at 88, in December 2018. The flag still hangs in Rachel’s home.