Life and death at Langhorne Speedway: The last ride of Larry Mann

Seventy years ago, a driver died during a NASCAR race for the first time. It happened in Bucks County, at the most challenging and dangerous track in the country. This is the untold story.

Larry Mann’s final lap in his final NASCAR race began with a gesture from a friend. Mann was approaching the first turn at Langhorne Speedway on Sunday, Sept. 14, 1952, during a 250-mile Grand National Circuit event — 250 miles, 250 laps. He was driving a green 1951 Hudson Hornet, moving at full speed along the far side of the track. According to stock-car superstition at the time, it was bad luck to drive a green car — green cars supposedly were prone to break down and crash — and sure enough, the Hornet wasn’t running well. Ralph Liguori, who had been one of Mann’s bunkmates as they traveled on the circuit, already had lapped him several times. Now he passed Mann once more, and as he did, he waved to him, as if to say goodbye.

What lap was Mann on when Liguori rumbled past him? Even contemporaneous accounts of what was about to happen differ on that question. One newspaper report said it was the 189th. Others said it was the 190th. An author and stock-car racing historian later wrote that it was the 211th. This would not be the only detail that, 70 years after Mann’s last ride and the first fatality in NASCAR history, would remain mysterious.

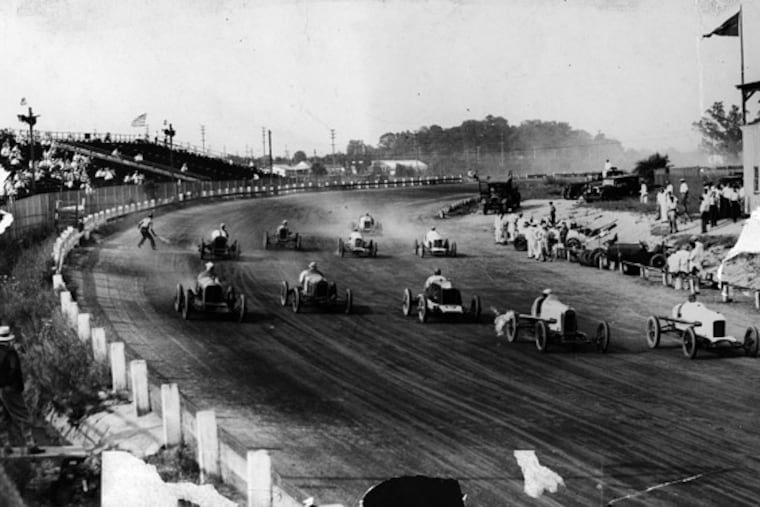

The most dangerous track in America

At Langhorne, there was always an atmosphere of thrill-seeking uneasiness, among the drivers and within the crowds, that mingled with the ever-present scents of oil and burned rubber wafting on the breeze. Its 100-mile National Open Championship, held annually from 1951 through 1971, was considered as prestigious as any car competition in the country, an East Coast answer to the Indianapolis 500. Yet no raceway was as punishing on a competitor’s body and mind. No raceway demanded more physical strength and mental exertion from the man behind the wheel just to keep himself alive.

Langhorne opened in June 1926. Less than two months later, more than 21 years before the advent of NASCAR, a driver died there for the first time. The track was a rutted circle of loose fill dirt with springs buried underneath, so dusty that one driver said he had no more than 20 feet of clear vision in front of him. Fans stopped showing up in 1928 because they couldn’t see the races through the brown-gray clouds. A promoter then poured thousands of gallons of used crankcase oil onto the track in 1930. As it seeped into the spongy earth, the oil tamped down the dust and stabilized the dirt … somewhat. Because of the slippery surface and steep turns — the most infamous stretch was the pothole-strewn, downhill plunge between the first two turns, known as “Puke Hollow” — a driver had to grip and rotate the steering wheel with all his might just to maintain enough traction between his tires and the track to prevent his car from careening into the guardrails.

The conditions that Mann and his fellow competitors were facing, though, were even worse than usual. By the race’s 2:30 p.m. starting time, a steady late-summer drizzle had softened what was already the most dangerous track in America until it was as slick as an ice floe. Through the first 210 laps, the 20,000 people watching from the grandstands witnessed five accidents.

Two weeks earlier, Carroll Reese, who was 17, had died at Langhorne when his motorcycle slammed into a concrete abutment during a race’s qualifying heat. The impact had launched Reese 15 feet into the air, according to one report, and he landed 20 yards away from his motorcycle. Still, if you were attending the Grand National event and were inclined to be optimistic, you could find a reason to believe that a similar tragedy wouldn’t befall a stock-car driver. NASCAR had been officially formed and incorporated in February 1948. Over the four years and seven months since, no driver anywhere in the United States had died during a NASCAR race.

The acceptance of risk

Larry Mann’s name was not Larry Mann. Born on April 3, 1924, in Jamaica, Queens, to Morris and Zelda Zuckerman, he adopted a different surname for his racing career, removing any reference to his being Jewish. He never offered a public explanation for the change. Trim and wiry at 5-foot-11 and 163 pounds, with short, dark hair and a hawk’s face, he completed three years of high school before enlisting in the Army Air Corps in October 1942, six months after he had turned 18, 10 months after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

It was not unusual for men who had served in World War II to return from their tours and find themselves drawn to stock-car racing, NASCAR analyst and former driver Kyle Petty said in a phone interview. They had seen and experienced so many atrocities and so much carnage that the element of danger inherent to racing didn’t bother them. An acceptance of life’s precariousness had penetrated and nested within their psyches as they walked from village to village in Italy or France, as they sprinted from one foxhole to another. That was the shared, unspoken bond among those drivers: They paid little attention to the peril in which they were placing themselves on the track. They knew how to bury their fears. Many of them had no choice.

“The risk was there,” said Petty, whose grandfather, Lee, and father, Richard, are regarded as two of the sport’s giants. “These guys were willing to take it because, financially, racing was a decent way to make a living.”

Not for Larry Mann. Not to that point. He had competed in five previous NASCAR races in 1952, collecting a total of less than $135 in earnings. He had worked as a post-office clerk and was still living in Queens, in Jackson Heights — another point of connection with Ralph Liguori, himself a native New Yorker.

The Grand National event would draw several of NASCAR’s best racers to Bucks County, Lee Petty among them, and its purse was more than $45,000, $35,000 of which would be distributed among the top five finishers. Mann had a wife, Abby. They had two children. He was 28 years old and in good health. Langhorne, he decided, was worth the risk.

‘I still feel bad about it’

After he passed and waved to Mann, Liguori came back around to find a horrifying scene. Mann’s Hornet had clipped the guardrail, and he had lost control of the car, which had flipped three times and torn through the fence surrounding the track.

“I don’t know if my waving distracted him or not,” Liguori told author L. Spencer Riggs in Riggs’ 2008 book, LANGHORNE! No Man’s Land. “But I still feel bad about it. It’s one of those things.”

Lee Petty had started the race in 24th position out of 44 cars. But using what Riggs described as a “smooth, steady drive,” Petty took the lead on the 209th lap and won in 3 hours, 55 minutes, and 40.16 seconds, the sixth of his 54 career victories on the circuit, his only one at Langhorne. His was one of just 28 cars to complete all 250 miles.

“When Granddaddy and those guys talked about Langhorne,” Kyle Petty said, “Langhorne was Indianapolis. Langhorne was Daytona. That was the top. There are places where, if you win one time there, you elevate yourself to God status.”

And there are places where a man’s life descends into obscurity in the same terrible instant that it ends. At 8:50 p.m., Larry Mann was pronounced dead at Nazareth Hospital in Northeast Philadelphia, 13 miles south of the track. His death certificate preserved the cold, spare facts of the incident: “LAWRENCE ZUCKERMAN (AKA LAWRENCE MANN … multiple injuries … while driving his stock car … in a race at Langhorne Speedway … crashed his auto against fence.”

The next day, the Bristol (Pa.) Daily Courier published a three-deck headline: “Second Fatal Accident of Season Occurs At Langhorne Speedway When Driver Loses Control of Racing Car and Hits Guard Rail.” But the accompanying story got Mann’s age and hometown wrong, saying that he was 36 and from White Plains. The United Press’ dispatch, sent to newspapers across the nation, had Mann’s age as 56. The Shreveport (La.) Journal ran four paragraphs of a wire-service story about the race, and Mann’s fate wasn’t mentioned until the fourth graph, after the report noted that Shreveport native Herschel Buchanan had finished third.

Marking the moment

Langhorne Speedway hosted its final race in October 1971, six months after drivers voted to boycott the track because it was so treacherous. Twenty-seven people had died there over its 45 years of existence. The track was razed soon thereafter. Rising out of its grounds now, at the intersection of Old Lincoln Highway and Woodbourne Road, are a shopping center and several large car repair shops and dealerships. A blue-and-gold marker from the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, mentioning Lee Petty and reminding onlookers that the speedway was known as the “Big Left Turn,” looms outside the windows of one dealership’s showroom.

Following Dale Earnhardt’s death at the 2001 Daytona 500, NASCAR implemented a series of technological innovations and measures to increase safety. The circuit is in the midst of its playoffs: Kansas Speedway last weekend, Bristol (Tenn.) Motor Speedway this Saturday, the sport forever changed for its reduced danger. “Drivers crawl in,” Kyle Petty said, “and never think about getting hurt.” Earnhardt was the 29th driver to die during a NASCAR competition. And the last, so far.

In July 2020, Ralph Liguori died at 93. If he still wondered whether his playful nod had contributed to Mann’s crash, he carried those doubts and that guilt with him to his grave.

“He never said a thing about it,” his son Frank said in a phone interview. “One thing about Dad, he never mentioned the guys who got killed.”

As a child, Kyle Petty, who is 62 and grew up steeped in racing’s culture and past, heard Larry Mann’s name often. He can remember being 6 or 7 years old, playing with drivers’ sons and daughters in the infields of various tracks, mothers abruptly scooping up those children and whisking them away after horrible wrecks, Petty never seeing them again. “Then you’re 14 or 15,” he said, “and you realize what happened.”

In that era, the roll call of the dead was never far from any driver’s mind or lips, and Petty’s family had such a strong link to Mann’s death, to this … what? This historical footnote? This morbid milestone? This moment from a time too distant to imagine or understand? You can’t say it’s trivia, because a 28-year-old man was killed and the word sounds too glib. No, you don’t dare call it that. But what do you call it?