Rysheed Jordan, ‘Prince of North Philly,’ returns home looking to pick up where he left off

Former Philly basketball star Rysheed Jordan is back and ready to make an impact in the community and on the court.

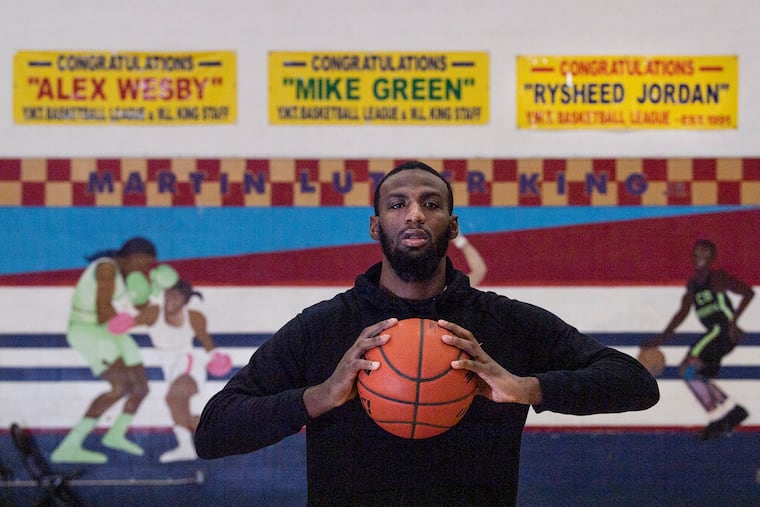

Rysheed Jordan stands inside the Martin Luther King Recreation Center in North Philadelphia. A banner hanging on the wall reads, “Congratulations Rysheed Jordan,” referencing his playing days in the city.

It’s a Friday in late January as he prepares to mentor children around the corner at William Dick School. A week earlier, he had schooled players on the basketball court in a 35-point performance with the Camden Monarchs.

On Sunday, he returned to the court for his third game with the semi-professional basketball team in the American Basketball Association at the Kroc Center in Camden, scoring 44 points with eight rebounds and eight assists.

These days, he’s limited to Philadelphia-area games because of travel restrictions as a result of his provisional release from prison in early December. But the limitations won’t prevent him from chasing his professional basketball dreams.

This is Jordan’s life now at 25, almost four years removed from being sentenced for attempted murder.

“I’m just trying to give back,” Jordan said last week. “All the kids that are doing wrong right now, just tightening them up and help fixing them up and stopping them early in their tracks before it’s too late.”

On the morning of Dec. 1, Jordan prepared to take his first steps as a free man in 3½ years. He wore a white T-shirt, gray Nike joggers, and Air Max 95 shoes. He walked past the metal detector at the State Correctional Institution at Laurel Highlands in Somerset, Pa., about four hours from the North Philly home where he grew up.

Family members greeted him in the lounge. Jordan flashed a big smile, giving out hugs to siblings, aunts, and former coaches like he used to dish out assists on the Philly playgrounds.

“It was crazy because a lot of people that I haven’t seen in years were happy to see me,” Jordan said. “How joyful everyone was and how I put a smile on everyone’s faces. That was a good thing.”

Influential player

Jordan was known as the “Prince of North Philly.” When he played, everyone packed inside the Robert Vaux High School gym. He was the link that brought everyone together in one of the city’s toughest neighborhoods.

“In the last 30 to 40 years, Rysheed has been one of the most influential players that we have had come out of this city,” said Kamal Yard, Jordan’s former AAU coach at Philly Pride.

But his influence came to an alarming halt. Jordan was arrested in June 2016 in connection with a shooting on the 1400 block of North 26th Street. He was later charged with attempted murder and sentenced to 3½ years.

Now that he’s home, Jordan is picking up where he left off by following his dream. He’s still as bouncy as ever and gained a little more wisdom.

On his second day out, he continued his quest of helping kids in the neighborhood by speaking with students at Mathematics, Civics, and Sciences Charter School. One month later, he carried on another pursuit: playing pro basketball.

The once top-ranked player in Pennsylvania and 17th-rated player in the ESPN100 knows he can do it. The plan is to play his way onto a roster overseas and then find his way to the NBA.

A month after his release, Jordan signed with the Monarchs. In his first game back, he slashed through defenses while showcasing the athleticism and scoring ability that made him a potential NBA first-round pick. He dropped 28 points off the bench.

“His play, attitude, and mindset has taken us to another level,” said the Monarchs coach, the Rev. Stan Laws. “He brings that hard-nosed, combat mentality defensively, and offensively he has an array of attributes.”

Growing up, Jordan stood out on the court. He was playing on the 17-under AAU team at 15 and shining.

“I was kind of stealing moves from him and watching him play,” said Rondae Hollis-Jefferson, the former Chester High star and current Toronto Raptors forward. “I liked his grit, and I liked his hustle.”

Off the court, it was all about loyalty and his city. He cared about everyone he knew, especially his mother, Amina Robinson, who was dealing with heart problems. While playing AAU, Yard would sometimes lie to Jordan about the length of trips because Jordan never wanted to leave his mother and six siblings for a long time.

“He’s one of those dudes that loves hard,” Yard said. “When he loves you, ain’t no turning back.”

His loyalty was displayed during his senior year of high school. Vaux High was scheduled to close down after the school year. He could have played at the top prep schools in the country. He considered attending St. Patrick’s (N.J.) but didn’t want to leave his mother.

So he stayed. He was the only Division I-caliber player on the team. As a guard at 6-foot-4, he was one of the tallest players on the team, too, but his sense of commitment wouldn’t allow him to leave.

As Yard put it, he remembers Jordan telling his mother, “I’m going to bring the colleges to the ‘hood.’ ”

“I was just trying to show people that it’s not all about jumping from school to school,” Jordan said. “Just play your game and do what you do. If you kill, you’re going to be noticed, no matter what.”

Jordan averaged 24.8 points in 2013, and became one of the most sought-after high school prospects in the country. Kansas, North Carolina, UCLA, and St. John’s were all going to the ‘hood.’

Originally, Jordan committed to UCLA, but a coaching change altered those plans. Once he decommitted, Temple and St. John’s emerged as favorites. His loyalty to North Philly and Temple would allow him to stay in town, but he chose the best of both worlds: St. John’s was close to home, but it was far enough away to limit the neighborhood distractions.

Jordan averaged 12 points and 3.1 assists in two years at St. John’s. He led the team in scoring as a sophomore but left the school after a coaching change and academic concerns. Jordan had heard that he was a projected late first-round NBA pick, but he was unable to enter the draft after missing the application deadline.

Because he was ineligible for the NBA draft, Jordan was later selected in the first round, fifth overall, in the NBA D-League draft by the Delaware 87ers.

But Jordan did not play well enough and was released after just 11 games. So he went back home to look after his mother and weigh his next decision.

Mature vision

Before he could return to basketball, Jordan was in handcuffs, facing a tougher obstacle than meeting a 7-footer at the rim. He was charged in June 2016 for a robbery that occurred in the Brewerytown section of Philadelphia. A botched stickup outside the Athletic Recreation Center resulted in a man’s being shot twice in the arm.

Video surveillance from the rec center showed Jordan running through a park to the rec center, and he confessed to the detectives during questioning that he was on the tape. Jordan faced 10 to 20 years but agreed to a plea deal that resulted in a shorter sentence. No one else was arrested.

“How I look at it, I just say, ‘wrong place, wrong time,’ ” Jordan said. “I don’t want anybody to think that I actually took the deal because I did it. I took the deal because I wanted the process to be over, and I wanted to get back home.”

The next 3½ years shaped the more mature version of Jordan that he believes he is today.

That bond started with his mother. The two spoke daily while Jordan was incarcerated, and she routinely took the four-hour trip to visit. With about two months left in his sentence, Jordan got a call and learned that his mother had died from heart problems.

He does not have a relationship with his father.

“It was hard because that’s all I knew," Jordan said. "She was my mom and my father.”

His support system became even more important. His aunts were there for him. The goals his mother wanted him to reach are now motivating him. Combine that with his love for basketball and the close relationship he has with his siblings, and you have a hungry guard who is ready to eat whatever opportunity is put on his plate.

In two months, Jordan has already returned and made an impact in his hometown. Living again in North Philadelphia, he’s done speaking engagements at schools, assisted Philly rapper Meek Mill with a toy drive, and displayed his talents on the court.

“I want [the children] to learn from my mistakes because everything they are doing or trying to do, I did it as far as basketball-wise and a little bit of streetwise,” Jordan said.

What could happen next could be a great ending.

“I’m trying to get to the highest level where I belong," Jordan said. "I’m going to put all the effort into getting there.”