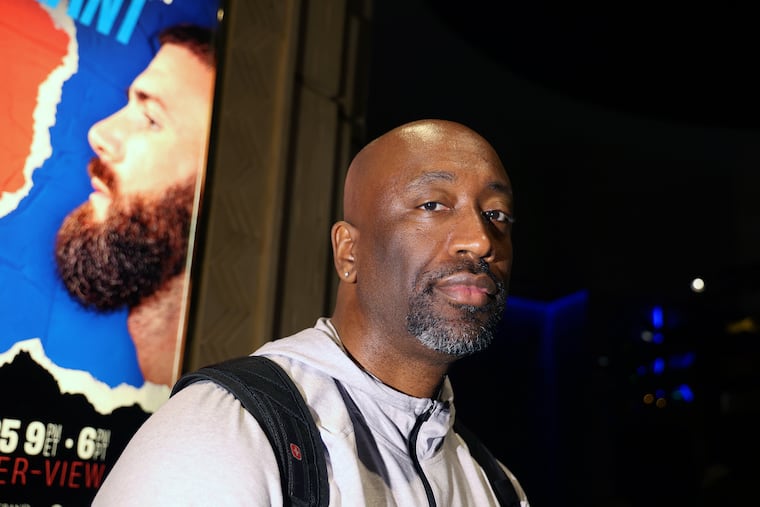

How former SEPTA bus driver Stephen Edwards became a world-champion boxing trainer

Nearly 20 years ago, Edwards swapped his CDL license for a boxing trainer’s license. He’s navigated the fighting world since, helping guide Caleb Plant and Julian Williams through successful careers.

The bus usually followed a route that started in North Philadelphia, rumbled south into Center City, and headed east for Penn’s Landing. Stephen Edwards learned how to maneuver that SEPTA bus through the narrow passages on 23rd Street, how to turn it onto Ridge Avenue, and then deal with the bustle of Market Street.

“Philadelphia is a tough place to drive a bus,” said Edwards. “I definitely didn’t want to do that too long.”

Edwards, born in West Philadelphia and raised in Uptown, drove a SEPTA bus for four years. The job was tough. And the schedule — which he received just a day before each shift — made it even more challenging.

But it was a rider who ultimately pushed him out.

“I had a guy try to fight me over the bus fare,” Edwards said. “That’s when I knew I had to leave.”

» READ MORE: The dark truth of Joe Fulks, Philadelphia’s first pro basketball legend

He soon swapped his CDL license for a pair of punching mitts. Instead of buses, he began to steer the career of a future world champion. Nearly 20 years later, the former SEPTA driver is one of boxing’s most respected trainers.

On Saturday night, Edwards will work the corner for Caleb Plant — one of the sport’s biggest draws — on Showtime pay-per-view. He has come a long way from the No. 33 bus.

“Everyone needs to start somewhere,” Edwards said. “No one is born a trainer. You have to have a starting point. Everyone. No matter what you do. No one is born doing anything. I just look at it like I’m doing something that I love and something that I’m good at. I expected to be successful as a trainer.”

Edwards grew up a boxing fan but didn’t train until he was in college at Temple. He played basketball at George Washington High School before a knee injury in his senior year extinguished those dreams. Edwards spent a couple of years sparring at some of the city’s top gyms — places like Champ’s and Joe Frazier’s in North Philly and Shuler’s in West Philly — to stay in shape.

He enjoyed it, but there were no plans to make boxing a career. That changed in 2009, when Edwards met Julian Williams, then a promising amateur boxer from West Philadelphia. Williams wanted Edwards to be his trainer.

Edwards was no longer working at SEPTA and had recently left his job as an addiction counselor to focus on his growing real-estate portfolio. He had time for Williams, who made his professional debut in 2010. Nine years later, Williams was a world champion with the former bus driver in his corner.

Edwards, best known as “Breadman” after picking up the nickname as a kid on the basketball courts, said he did it his way. He ignored the skeptics who filled the gym in West Philadelphia and stayed away from the gossip spread by rival trainers. He studied the way Naazim Richardson, the famous trainer who died in 2020, worked with his fighters and steered clear of everyone else.

“It was an animalistic world,” Edwards said. “Everyone wanted to outdo each other and it was very competitive. It could be vicious at times. I just had blinders on and said, ‘I’m going to do whatever I have to do to make this kid a world champion.’

“There would be mornings where I didn’t feel like waking up and meeting Julian at the track, but I would do it just to shut everyone up. I was doing it to build a world champion. I was saying, ‘I’m going to be the head trainer of a world champion.’ It gave me a lot of fuel and made me work really, really hard.”

Edwards never fought as an amateur or professional, making him an outsider when he started training fighters at 34 years old. But his work ethic — the one he used every day behind the wheel of a SEPTA bus — kept him going.

He left his Northeast Philadelphia home every morning to meet Williams in Upper Darby, where they would run on a track before sunrise. Edwards returned home, napped, and headed to West Philly to train Williams in the gym. The fighter, homeless as a teenager, was hungry to be world champion. So was the trainer.

“You can’t cheat the grind,” Edwards said.

Edwards and Williams split two years ago and he connected last year with Plant, who had just lost his super-middleweight title in November 2021 to Canelo Alvarez. Their first fight together ended with a knockout in October 2022 against former champ Anthony Dirrell. With Edwards, Plant (22-1, 13 knockouts) seems reinvigorated headed into Saturday’s bout against David Benavidez (26-0, 23 KOs) at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

Edwards credits his success to his ability to connect with fighters. Williams was a broke teenager when he met Edwards. Plant was already a millionaire world champion when he asked Edwards to train him. The fighters were at opposite points in their careers and Edwards found a way to better both of them.

“Everyone learns differently,” Edwards said. “Some people learn visually. Some people learn through hearing things. Some people learn through you showing them things. Some people need to apply repetitions over and over and over again. Some guys get it right away. I’m very, very considerate that everyone does not learn the same way.

“I have a lot of patience for guys because every guy I’ve trained is different. You have to talk to them differently. I just have a lot of understanding of how to deal with people. They need to perform under pressure and on top of that they’re getting punched. It’s not easy. It’s not difficult for me because it’s just something I like to do. If you’re doing what you like, then you don’t view it as work.”

» READ MORE: Zack Steffen opens up about missing the World Cup and returning to the USMNT this month

The hardest part now of Edwards’ job is the travel. He flies every Monday morning to Las Vegas, where he trains Plant, before flying home to Philadelphia on Friday. But that route can’t compare with the one the old bus driver used to navigate every day through the city.

“I’ve had real jobs,” Edwards said. “I have a lot of appreciation for everyone like that. I don’t have to be here. I’ve had some tough jobs in my life. I’ve had to grind for everything I have in my life. Being a boxing trainer is work. I just don’t view it as work. It’s not work for me.

“Some days, I’m tired. Some days, guys miss punches and hit you. But I find it enjoyable. I enjoy what I’m doing. You know when you have a job and you’re like, ‘Oh my God. I can’t believe I have to go into this place today.’ I don’t feel like that about boxing.”