Serious car crashes down 34% on Philly streets with traffic-calming measures, city says

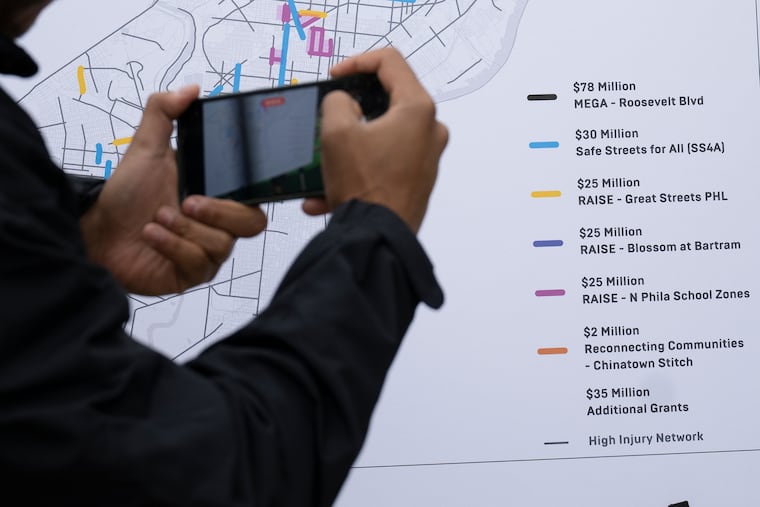

Philadelphia has $220 million, a good share of it from the federal infrastructure act, to continue the complete streets projects.

The statistics are in, and crashes with fatalities or serious injuries have dropped 34% on the dozens of streets in Philadelphia that have been reconfigured in safety projects to slow motor vehicles and protect pedestrians and bicyclists, city officials said Tuesday.

That conclusion was based on comparing crash data on 35 stretches of roadway where the city or PennDot has built traffic-calming features with the number and severity of collisions on similar streets that were not changed.

“We wanted to understand whether this work was worthwhile and whether it was paying off — and we have great news,” said Mike Carroll, the city’s deputy managing director for transportation and infrastructure.

Behind him was Cobbs Creek Parkway, a winding and narrow road notorious for speeding and crashes. Neighbors say traffic has been tamed considerably since 2021 when PennDot installed speed tables that force drivers to slow down as they pass over, as well as lane separators and rumble strips.

Councilmember Jamie Gauthier, who represents West and Southwest Philadelphia, said that the improvements were made when Mayor Jim Kenney prioritized Vision Zero — the city’s goal of eliminating traffic deaths — in 2016, following “generations of inaction” and years of Cobbs Creek residents demanding safety improvements after horrific crashes.

“For me empowering the community to shape their own neighborhoods is a central tenet of our Complete Streets approach, because this is a racial justice issue as much as it is a safety issue,” Gauthier said. “Historically, the most dangerous roads tend to be those in working-class Black and brown neighborhoods like this one.”

Complete Streets is a road-design approach that seeks to make roadways safer for all users, including pedestrians and cyclists, as well as drivers of motor vehicles.

Philadelphia has three types of Complete Streets projects:

Road diets, which remove vehicle travel lanes and reallocate space to pedestrians and cyclists. This measure was taken on Chestnut Street, Market Street, JFK Boulevard, and American Street. Road-diet projects resulted in 18% fewer injury crashes a 25% decline in speeding, without a decline in traffic volume, the city says.

Separated bike lanes, which use buffers and reflector posts to keep bikes away from car and truck traffic. Examples include Ryan Avenue, 11th Street, and 6th Street. This approach resulted in 17% fewer injury crashes.

Neighborhood Slow Zones, which involves the installation of traffic calming measures, often around schools. Since the first two were installed in Fairhill and around Willard Elementary School in 2022, the zones have had no fatal or serious injury crashes. All reported crashes in the zones are down 75%.

Officials used PennDot crash data from 2012 through 2022 on the city’s high-injury network, the 12% of Philadelphia streets with 80% of the fatal and serious-injury crashes. That allowed planners to have at least four years of “before” data and a minimum of one year of “after” data for each project.

In addition, the 35 traffic-calming projects studied — all of them on the high-injury network — were measured against the other roadways on the network that did not have any traffic-calming measures installed.

“It’s like a drug trial, comparing a control group that gets a placebo with a group that gets the treatment,” said Kelly Yemen, director of the city’s Office of Complete Streets.

City officials said they’ve got $220 million in federal, state and local grants to keep complete-streets projects in the pipeline for several years. And PennDot will soon install traffic-calming devices on Lincoln Drive, one of the city’s most notoriously dangerous roads.

The city’s 2023 Vision Zero report, which disclosed the results of the street safety projects, also found that 124 people were killed in traffic crashes in Philadelphia, with sharp increases in the number of people killed while walking or riding a bike.

Traffic violence has been felt most acutely among Black and Hispanic Philadelphians, relative to their share of the city’s population, the report said. Half of those who died in traffic crashes between 2020-2022 were Black people, who represent 40% of the city’s population.