SEPTA workers authorized a strike for the fourth year in a row. Here’s when they walked off the job in the past.

The Transport Workers Union, now in negotiations with SEPTA, has gone out on strike before. So have other SEPTA unions. Here is what happened in previous strikes.

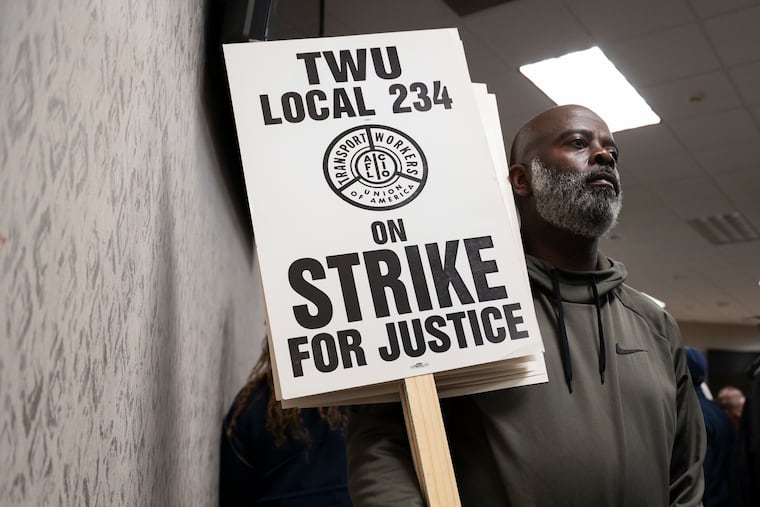

Members of the Transport Workers Union Local 234 on Sunday, Nov. 16 voted to authorize a strike if union and SEPTA negotiators can’t reach an agreement on a new contract.

Shortly before the current contract ran out at 11:59 p.m. on Nov. 7, TWU’s new president, Will Vera, urged union members to stay on the job. In an unusual move, he delayed a strike vote at the time of contract expiration, saying he had hope that a deal could be reached without the usual brinksmanship.

“We’re asking you to please continue to come to work and put money aside. We want you to be prepared in case we have to call a work stoppage,” he told members in a video at the time.

Local 234 leaders say they’re prioritizing a two-year deal with raises and changes to what the union views as onerous work rules, including the transit agency’s use of a third party that Vera said makes it hard for members to use their allotted sick time.

Three TWU contracts in a row have run for one year each, all negotiated as SEPTA weathered what it has called the worst period of financial turmoil in its history.

In a statement, SEPTA said it was aware of the authorization vote and is committed “to continue to engage in good-faith negotiations, with the goal of reaching a new agreement that is fair.”

SEPTA unions have walked off the job at least 12 times since 1975, earning the authority a reputation as the most strike-prone big transit agency in the U.S.

Here is what happened in previous SEPTA strikes:

2023 Fraternal Order of Transit Police Lodge 109 (three days)

SEPTA police officers walked off the job after bargaining with the transit agency for almost nine months, largely over the timing of a 13% pay raise for members. The agreement, partially brokered by Gov. Josh Shapiro, came amid heightened fears about safety on public transit and a funding crisis for SEPTA.

» READ MORE: SEPTA’s transit police union vote to ratify a new contract (from 2023)

2016 TWU Local 234 (six days)

TWU Local 234 walked off the job for six days; the biggest issue was retirement benefits. SEPTA’s contributions toward union members’ pensions did not rise in tandem with wages when workers made more than $50,000. Managers’ pension benefits were not capped. The union also wanted to reduce out-of-pocket health-care costs and win longer breaks for bus, trolley, and subway operators between shifts and route changes.

SEPTA and the union reached an agreement Nov. 7, the day before the general election. Democrat Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign was worried about voter turnout, and the city sought an injunction to end the strike. It proved unnecessary.

» READ MORE: SEPTA deal, reached at 5 a.m., will raise wages and health contributions (from November 2016)

2009: TWU Local 234 (six days)

Talk about leverage. TWU was ready to strike just before the first home game of the World Series between the Phillies and the New York Yankees. Gov. Ed Rendell pushed the two sides to continue talking, and the transit workers waited to walk out until three hours after the end of Game 5, the last in the series played at Citizens Bank Park.

It was a bitter strike, coming just a year after the stock market’s meltdown started the Great Recession. TWULocal 234 President Willie Brown called himself “the most hated man” in Philadelphia. Mayor Michael Nutter was harshly critical. Brown called him “Little Caesar.”

The strike was settled Nov. 7 with a deal on a five-year contract. Transit workers got a $1,250 bonus, a 2.5% raise in the second year, a graduated increase in SEPTA pension contributions from 2% to 3.5%, and the maximum pension benefit was raised to $30,000 from $27,000.

2005: TWU Local 234 and United Transportation Union Local 1594 (seven days)

Two unions walked off the job on Halloween, halting most bus, subway, and trolley service in Philadelphia and its Pennsylvania suburbs.

Negotiations collapsed mostly over SEPTA’s insistence that workers pay 5% of medical insurance premiums. At that point, the authority paid 100% of the workers’ premiums for family coverage.

In the end, it was solved by Gov. Rendell, a Democrat who had been Philadelphia mayor in the 1990s. He agreed to give promised state money to SEPTA early, so it could pay premiums in advance, reducing its costs.

In the resulting four-year deal, the unions had to pay for 1% of their medical premiums. They also received 3% yearly raises.

1998: TWU Local 234 (40 days)

City transit workers’ contract expired in March, but they did not strike until June — and then stayed out for 40 days. The two sides reached an agreement in July, but it fell apart. TWU members had returned to their jobs and kept working under an extension of their old contract. A final agreement was signed Oct. 23.

The union agreed to SEPTA’s demand that injured-on-duty benefits be limited. The old contract gave them full pay and benefits while on leave after a work injury. SEPTA wanted to hire an unlimited number of part-time workers. The union agreed to 100 part-timers to drive small buses.

SEPTA’s chief negotiator was David L. Cohen, famous for reining in unions representing city workers during Philadelphia’s bankruptcy in 1992, as Rendell’s mayoral chief of staff.

» READ MORE: What you need to know about a possible SEPTA strike

1995: Local 234 TWU (14 days)

A two-week strike stilled city buses, trolleys and subways until an agreement was reached April 10. Transit workers would get 3% raises per year over the three-year span of the new contract, as well as increases in pension benefits and sick pay.

The union agreed to several cost-reduction measures, including a restructuring of SEPTA’s workers compensation policies.

Mayor Ed Rendell, a villain to many in labor for winning givebacks from city unions in 1992, pushed SEPTA to offer more generous terms to TWU than it had initially. Cohen, who was his chief of staff, crunched the numbers to make it work. Three years later, out of the city administration and working as a lawyer, he was hired as SEPTA’s chief negotiator.

1986: TWU Local 234 (four days) and UTU Local 1594 (61 days)

When TWU struck the city transit division in March 1986 over a variety of economic issues and work rules, some bus drivers pulled over mid-route and told passengers to dismount, The Inquirer reported.

Members were particularly incensed at what they considered SEPTA’s draconian disciplinary procedures. Union leaders said the issue was a basic lack of respect. The strike was settled in four days.

Drivers for 23 suburban bus routes, two trolley lines in Delaware County and the Norristown High-Speed Line — all members of the United Transportation Union — struck for just over two months, affecting about 30,000 passengers a day.

Employees in what was then known as SEPTA’s Red Arrow Division — after the private transit company that used to own the routes and lines — made considerably less than their city counterparts and had weaker pension benefits. They won raises and pension changes that brought them closer to parity.

1983: Regional Rail (108 days)

Thirteen separate unions walked off the job on the commuter rail lines that SEPTA had taken over at the beginning of the year from Conrail, successor to the bankrupt Pennsylvania and Reading Railroads.

In addition to wages, a key issue was SEPTA’s demand that union train conductors accept pay cuts. The authority had already cut the number of those workers by more than half.

Eventually SEPTA reached deals with a dozen of the unions. The 13th local, which represented 44 railroad signalmen, held out longer. Main issue: Whether SEPTA had the right to contract with outside firms for some types of signal work.

The Regional Rail strike remains SEPTA’s longest work stoppage since 1975.

» READ MORE: SEPTA transit workers vote to authorize a strike if needed

1982: TWU Local 234 (34 days)

About 36 suburban bus drivers and mechanics operating routes primarily in Montgomery County, and some routes in Bucks, won an 8.5% wage increase over three years.

The bus routes were the descendants of the Schuylkill Valley Lines and the Trenton-Philadelphia Coach Lines, which SEPTA acquired in 1976 and 1983, respectively. Service has grown, and the collection of bus routes is known as the Frontier Division today.

1981: TWU Local 234 (19 days) and UTU Local 1594 (46 days)

Transit workers shut down buses, trolleys and subways in the city on March 15, seeking job security in the form of a no-layoff clause, wage increases and a bar on SEPTA hiring part-time workers.

And the Red Arrow division went out for 46 days seeking higher wages and better medical benefits. SEPTA also backed down a demand for permission to hire private contractors for some work on the suburban buses, trolleys, and the Norristown High Speed Line.

1977: TWU Local 234 (44 days)

After a bitter strike, union members who run the city transit division got higher wages and more benefits, after rejecting an arbitrator’s proposed contract that was portrayed in news reports as generous.

A furious Mayor Frank Rizzo told reporters the strike “can last 10 years for all I care.” He said of the union’s rejection of the earlier offer: “It is outrageous, and I hope the people won’t forget it.”

1975: TWU Local 234 (11 days)

Transit workers, concerned about the ravages of inflation, wanted a clause giving them cost-of-living increases and enhancements to health-care benefits. Those were granted after Rizzo agreed to add $7.5 million to the city’s annual SEPTA contribution. Perhaps that’s one reason the mayor was so annoyed two years later.

Staff writer Erica Palan contributed to this article.