Only Philadelphians can navigate SEPTA. That’s going to change.

At the least, there could be upgrades to signs and maps. At the most, SEPTA could go so far as to renaming the trolley, Market-Frankford, Broad Street, and Norristown High Speed Lines.

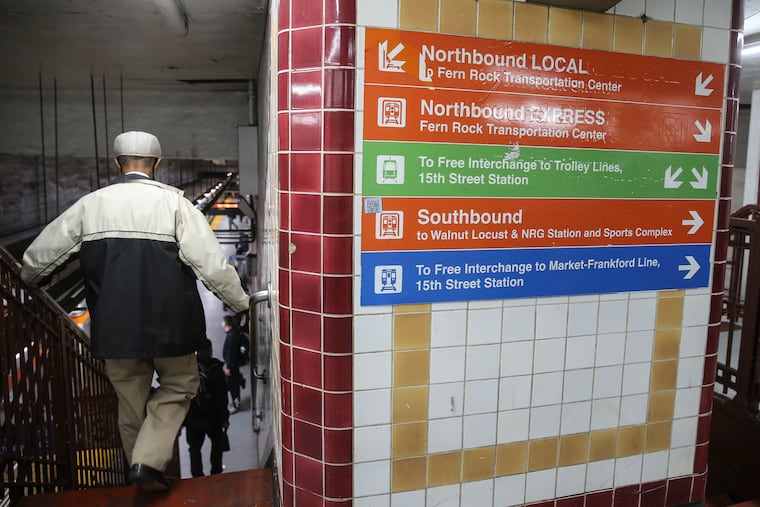

Getting around on SEPTA, the sixth largest transit agency in the country, feels like a labyrinth.

It can be confusing to understand how one part of its system connects to the other. With a lack of clear communication and obvious signage, learning how to confidently navigate SEPTA’s underground passageways is a rite of passage for many Philadelphians. The problem for the decades-old system isn’t new, but a solution will be.

SEPTA is in the beginning phase of its “Rail Transit Wayfinding Master Plan,” a comprehensive overhaul that at the least upgrades signs and maps to make SEPTA easier to use, but at most could go so far as to rename the trolley, Market-Frankford, Broad Street, and Norristown High Speed lines. The project comes at a time when rideshare companies send instantaneous alerts to notify of a driver’s location and arrival time, but SEPTA users are left to consult PDF timetables or its many social media accounts for updates.

“We’ve said for a long time that SEPTA’s kind of like a native language," said Lex Powers, SEPTA strategic planning manager and the wayfinding project manager. “The people who are born, raised here, learn how to use SEPTA from their community, from their parents, for school. It can be hard to put yourself in the shoes of someone who is new and figuring it out for the first time."

Whether its people with disabilities looking for ADA-accessible entrances and exits, non-native English-speakers grasping for a translation of the Market-Frankford Line, or tourists determining how to get to West Philadelphia despite the neighborhood not explicitly appearing on a transit map, the aim is to make the system easier to use.

SEPTA has already started outreach efforts with Philadelphia’s Office of Transportation, Infrastructure, and Sustainability, as well as community groups, Powers said. A survey, available in English, Spanish, and Chinese, is open to the public to collect feedback until early November.

Asked if she’s heard from riders who have trouble navigating SEPTA, General Manager Leslie Richards was quick to respond.

“I saw it myself," Richards said. "I grew up in the area, and I realized that I have an inherent knowledge of how to get around on the system because I grew up on the system, but when friends would come from outside the area, I could see how confused they were.”

» READ MORE: SEPTA to launch new three-day passes, fit for the COVID-19 era

Richards made wayfinding and signage a top priority when starting her role less than a year ago. The overarching goal is to make riding transit intuitive, and to treat SEPTA by the sum of its parts.

“It always bothered me that when I asked people, do they ride SEPTA," she said. "They were like, ‘Oh, I’m a train rider, or I’m a subway [rider].’ No one looks at all the modes.”

She’s called both “instrumental” in getting the project off the ground as well as “a game changer” by Powers and Will Herzog, chair of the SEPTA Youth Advisory Council, an outreach group.

Communication was lowest ranked in a 2018 customer survey asking riders to rate several factors, including convenience, courtesy, and personal safety. A Twitter account, @SeptaUXman, teases at blindspots.

Taking on what could be a true rebrand of a major transit network is no easy task, especially in a city as nostalgic as Philadelphia. Ask any West Philadelphian, and they’ll explain what “Step Down" means. Ask those who still refer to NRG and Jefferson Stations as Pattison Avenue or Market East Stations. Ask anyone who’s turned an old SEPTA token into jewelry or a keychain.

“This is that tricky balance," Powers said. "We also don’t want to erase things that people care about, and we wouldn’t. How do you provide a secondary way to refer to these lines more easily for newcomers while also keeping what is culturally important.”

While the authority has never tackled a project as extensive as the wayfinding plan, there was a related effort in the early 1980s to refer to SEPTA lines by their respective colors.

» READ MORE: Philadelphia’s traffic congestion was bad before the pandemic. It could get worse.

“When strangers come into Penn,” said a city official at the time, “as thousands do every year, they are told to take the subway-surface cars to the Market-Frankford Subway-Elevated to get downtown. Isn’t it nicer to say, ‘Take the Green Line to the Blue Line?’”

The plan received pushback, advised to “be sent back to the drawing boards unless there is also a plan afoot to rename Broad Street Orange Street," The Inquirer wrote in an editorial.

“SEPTA is confusing, but renaming is not the solution," wrote a reader in a letter to the editor. “The solution lies in improving SEPTA’s poor signage, scanty information system, and non-existent marketing program.”

Riders could start to see some changes to signs and maps as early as next year and SEPTA would then seek further feedback, though there’s not yet a definitive timeline on the project. It couldn’t tout the advantages of a unified system until this summer when SEPTA began to offer riders one free transfer.

SEPTA is getting help from Entro, a design firm, through a year-long, $360,000 contract. The University of Pennsylvania Center for Safe Mobility too will lend a hand, using eye-tracking technology that measures where riders feel confused or stressed.

“We’re in a new era now, and we need to plan for that era, and we need to design for that era," said Carrie Long, the center’s director. “We not only want to reengage the riders we have, but we want to get more.”

» READ MORE: SEPTA was attacked by ransomware, sources say. It’s still restoring operations stifled since August.

The wayfinding initiative is highlighted in SEPTA’s “Move Better Together” COVID-19 “recovery plan,” a guide on what the authority has done in response to the pandemic, and what it will do to appeal to more riders.

The easier SEPTA makes its system to use, the more people will be drawn to riding, and passengers are sorely needed. Ridership is down about 65% on trolleys, buses, as well as the Market-Frankford and Broad Street Lines.

While the authority has required mask wearing and enhanced cleaning efforts, some still prefer the safety a private car provides from COVID-19. There’s concern that whatever new transportation habits riders adopt will stick well after a wider reopening of the economy or the introduction of a vaccine.

Of course, lower ridership also means far fewer fare dollars, now losing $1 million a day. SEPTA can’t afford to not prioritize the project, said Herzog, of the YAC.

“It’s pocket change compared to other projects," he said. "But this will have such a deep and all encompassing impact.”