Washington Avenue will vary between 3 and 5 lanes under latest redesign

Protected bicycle lanes will be installed on 18 blocks, and business owners will get marked loading zones and vehicle parking outside of travel lanes.

Washington Avenue will be put on a mixed road diet with the number of lanes varying by section and get new traffic-calming changes when it is repaved later this year, city officials announced Tuesday. This latest configuration comes after nine years of analysis and contentious debate over safety and convenience on the South Philadelphia corridor.

“We feel this approach is going to substantially improve the safety over what people see today,” said city Deputy Managing Director Mike Carroll, who leads the Office of Transportation, Infrastructure and Sustainability. “That’s the main goal we’ve had all along.”

Four blocks of the avenue will retain the existing five-lane configuration, on either side of Broad Street, eight blocks will slim down to four lanes, and 10 blocks will narrow to three lanes, officials said.

Protected bicycle lanes will be installed on 18 of the blocks; business owners will get marked loading zones and parking spaces outside of travel lanes, officials said, to reduce double-parking as well as congestion caused by deliveries.

Carroll said many crashes involving pedestrians happen when drivers turn onto or off the avenue, and the city plans to use rumble strips and “corner wedges,” bumps marked off by yellow striping to guide vehicles away from people crossing the street.

The decision was reached after a backlash against OTIS’ original plan, announced in September 2020, to narrow the entire 2.1-mile stretch of Washington Avenue from five vehicle travel lanes to three — a design meant to cut vehicle crashes, make walking safer, and protect cyclists by placing bike lanes between parked cars and curbs.

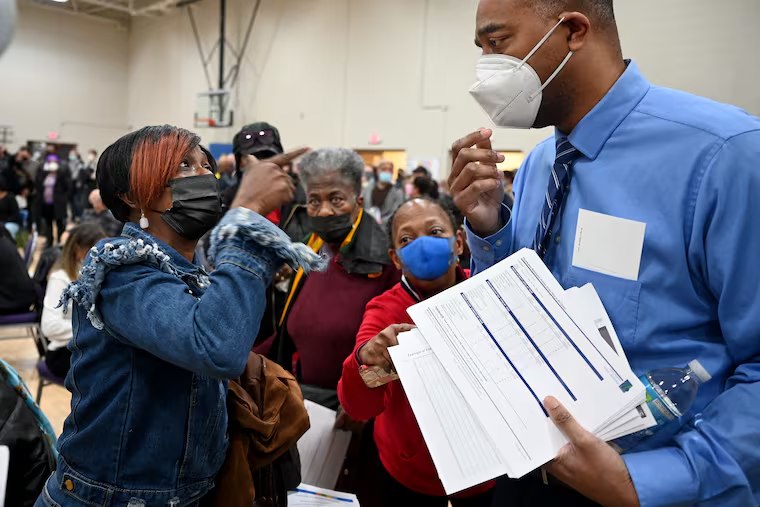

City officials dropped that plan Feb. 6. They had reopened the public-engagement process last year because they said the earlier round in 2020 did not adequately represent the concerns of people of color in the Grays Ferry and Point Breeze neighborhoods, as well as business owners along the avenue. Black and brown communities have historically been bystanders in big city transportation decisions.

All of that has been taking place amid rapid change in the neighborhoods north and south of Washington Avenue, including Point Breeze, where development and escalating home values have pushed out some longtime residents.

» READ MORE: The secret to making gentrification benefit Philadelphia's low-income homeowners

At an open house in the Christian Street YMCA on Tuesday evening, many in the crowd began booing as Carroll was winding up his presentation of the new plan.

“Liar!” several people shouted.

He stopped talking and said residents could ask questions of OTIS staff stationed around the room.

”I see a lot of mixed reactions,” said City Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson, who represents the western end of Washington Avenue. He said he wants to have “conversations” with constituents. But he praised OTIS for pausing the process to include input from longtime Point Breeze residents who were not consulted earlier.

“No one likes everything about it,” said Albert Littlepage, a Point Breeze community leader who had opposed major changes. “We’ve got to compromise, though, and get the best result we can.”

Nicole Brunet, an organizer with Penn Environment who lives in Fitler Square but crosses Washington Avenue on her way to work, said it was appalling that the two blocks on either side of Broad Street will remain at five lanes — the most congested and accident prone part of the roadway.

”I’m looking at how to move past it, how OTIS can have a better engagement process the next time,” she said.

Several people said they were concerned about how traffic would transition between sections.

Some Point Breeze residents said they believe the intent of the traffic-calming design is to abet development, which would only accelerate changes to the neighborhood that have displaced many residents in the historically Black neighborhood.

It wasn’t news to OTIS or anyone involved in 2014, when proposals to change Washington Avenue were last seriously discussed, that marginalized groups were often excluded from planning, said Will Tung, whose child attends a school near the avenue.

“Instead of opening the process to more people, OTIS instead chose to narrow it,” Tung, a member of the urbanist group 5th Square, said Tuesday. “There was no push to involve new voices, only closed-door meetings with unelected, self-proclaimed leaders.”

To road safety advocates, the decision to abandon the full three-lane plan, which OTIS planners determined would be the safest option of those under consideration, was less about equity, as city leaders said, and more about the influence some communities and their leaders have with members of City Council.

» READ MORE: How a redesign of Washington Avenue got detoured by a clash of competing needs

In Philadelphia, the lawmakers have a great deal of informal power over decisions on land-use and transportation projects. Council members traditionally defer to colleagues in matters affecting their districts.

Members of groups like the 5th Square political action committee and the Bicycle Coalition say that Council resistance has often kept changes with potential safety and environmental benefits from happening.

Carroll said OTIS tried hard to get socioeconomically diverse members of the working groups it met with beginning last fall, including renters, but also was wary of letting the panels get too large.

“Our experience is that when a group gets to be too big, you sort of break down the opportunity for conversations and end up with ... a speech-making, sloganeering dynamic,” he said.

Going forward, Council will need to pass legislation to enable the new parking and loading regulations, Carroll said. He said he’s hopeful it will be approved, but “it’s out of the administration’s hands at this point.”

City officials would like to begin making the changes this summer at the same time the avenue is scheduled to be repaved for the first time since 2003.

Repaving and adding new lane markings will cost about $6.2 million, most from federal funds, OTIS said. The cost to the city: $ 1.24 million.

Officials estimate the other elements, such as speed cushions and bus-boarding islands, will cost about $2 million, an OTIS spokesperson said. Those items must first be designed, then contractors will bid on the project.

There were 254 crashes on Washington Avenue between 2012 and 2018, the city says. Four people died in these crashes, and six people were seriously injured. That earned the corridor a spot on the city’s high-injury network: 12% of surface streets in the city with 80% of the crashes that kill or seriously injure people in cars, pedestrians, and cyclists.

City officials have been tracking the safety data, based on PennDot crash reports, as part of its Vision Zero pledge to reduce traffic deaths in Philadelphia to zero by 2030.

This story has been updated to clarify the projected costs of the Washington Avenue redesign.