Workers at two Philly Starbucks stores want to unionize

Workers at two Starbucks stores in Philadelphia have petitioned for a vote to unionize. They join a small — but growing — labor movement at the coffee giant.

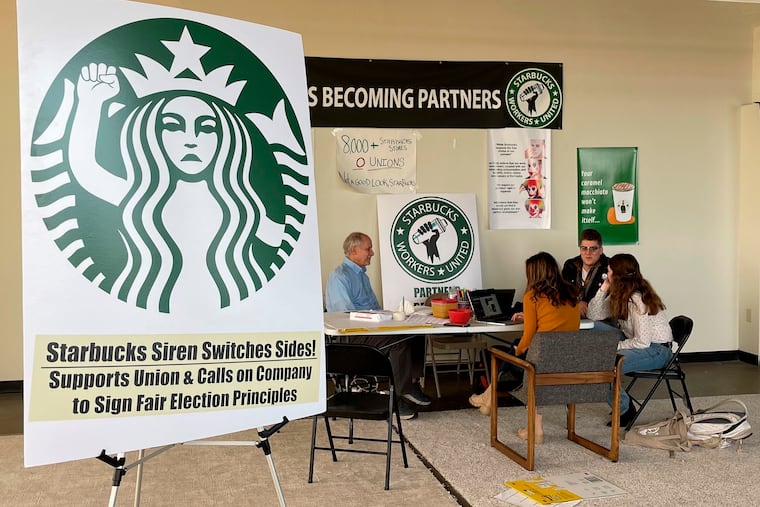

Starbucks workers at two Philadelphia stores took a key step in forming a union last Friday, accelerating a budding labor movement at the coffee giant that has seen employees at dozens of the chain’s locations nationwide try to organize.

Baristas at the 1945 Callowhill St. and 600 South Ninth St. stores filed petitions to hold elections on union representation with the National Labor Relations Board, a first step in the process. The unionizing effort took root in December when two Starbucks stores in Buffalo, N.Y., voted to join Workers United, an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union.

So far, workers at more than 50 stores across the country have launched the process to join the union, according to spokesperson Dawn Ang.

The Seattle-based company has steadfastly said it’s against employees unionizing. “We are listening and learning from the partners in these stores. However our stance has not changed,” said a Starbucks spokesperson in a statement Monday.

Still, the number of unionizing locations is a small fraction of Starbucks’ 9,000 company-owned stores and 6,500 licensed stores.

Workers United represents more than 86,000 workers in the apparel, laundry, food service, hospitality, nonprofit, warehouse, and manufacturing industries in the U.S. and Canada. The organization is headquartered in Philadelphia.

Wages rising, union membership falling

The pandemic has contributed to crosscurrents in the workplace, economic observers say. Unemployment soared in the early days of the health crisis. Yet many industries report difficulty filling empty positions, helping stoke wage increases. Workers are reportedly quitting jobs in droves and demanding better compensation and benefits. But the so-called Great Resignation, the phrase coined for the emboldened American workforce, has so far not translated into a boost in union membership.

“We have a labor market that’s relatively strong, unemployment’s dropped to 3.9%, workers are bidding up wages. It’s an economy that’s getting itself on a self-sustaining path,” said San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank president Mary Daly on Tuesday. Four million workers haven’t returned to the workforce since the pandemic.

Unionized workers at Deere, Kellogg and Mondelez International have walked off the job during recent labor battles. Wage data point at the negotiating power of unions: Nonunion workers earn less, receiving median weekly earnings that total 83% of those paid to unionized workers ($975 vs. $1,169), according to 2021 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Lower-wage occupations and industries continue to see the fastest growth in wages,” said Benjamin Harris, assistant secretary for economy policy at the U.S. Treasury on Monday.

But the overall number of full-time workers in unions has declined by 241,000 workers in 2021 from the prior year to 14 million, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

And the number of petitions for a representation election, an initial step in unionizing, has dropped 42% between 2015 and last year, according to the NLRB.

Starbucks may aim to circumvent the unionization movement: in Manhattan, the company last year joined with Amazon to open a cashierless store.

In 2020, Starbucks said it planned to close 400 underperforming stores and replace those with pickup locations or focus on curbside or drive-thru service. Even before the pandemic, Starbucks said 80% of its U.S. transactions were on-the-go orders.

“From the beginning, we’ve been clear in our belief that we do not want a union between us and partners, and that conviction has not changed,” wrote Rossann Williams, executive vice president, president North America, in a December letter. Starbucks refers to its employees as partners.

“We believe direct communication between partners has made our company what it is today. We’re also going to respect our partners’ right to organize.”

Lua Riley, who works at Starbucks’ Ninth and South Streets location, said the biggest reason to file for a union was “we realized people were not making the compensation they deserved vs. their peers.”

The Buffalo union filing “emboldened us, but it was inevitable that Starbucks in Philly would unionize. Buffalo just pushed up the timetable.”

When Riley began working at Starbucks many new employees were making more than the person training them. “That’s why part of our demand is for pay transparency.”

The Philadelphia Inquirer is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. See all of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.