Penn Relays enter esports world with gaming event on Minecraft-built Franklin Field

Penn hired esports company Gen.G to build a virtual replica stadium, then invited local students, coaches and fans to play in a relay-style gaming competition.

The big arched gates on 33rd Street are locked this weekend, as they have been for more than a month because of the coronavirus pandemic. But the Penn Relays found a way to throw a party on their traditional weekend anyway, holding an esports gaming competition Friday at a virtual Franklin Field.

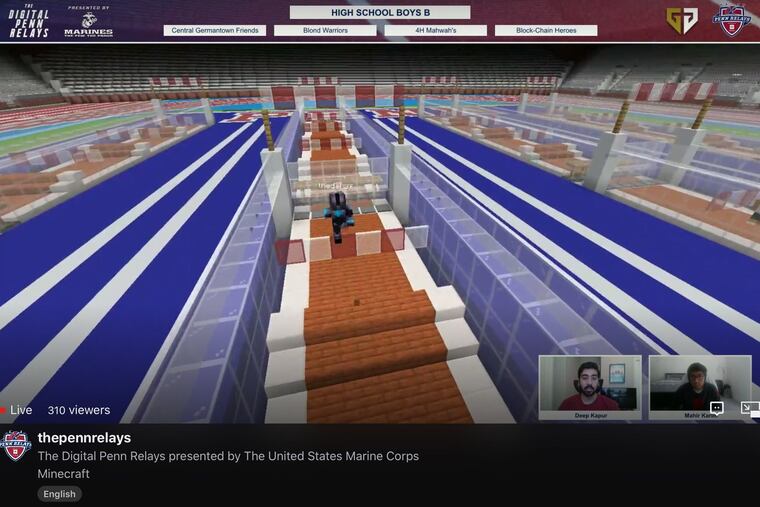

Penn hired Gen.G, an esports company with headquarters in Los Angeles, Seoul, and Shanghai, to build a replica stadium in the popular video game Minecraft. It looked good, with real detail in the brick walls, bleachers, and horseshoe-shaped end zone.

The event was broadcast on Amazon-owned streaming platform Twitch, which is hugely popular with the esports community and kids who play video games.

Competitors didn’t wear college or high school uniforms, to be sure, and most of them didn’t even look like regular humans. They were Minecraft avatars, running and jumping on courses laid the length of the football field.

But that was part of the fun, watching a penguin suit and a scuba diver and a Star Wars stormtrooper. And there was a competitor in something close enough to a Penn outfit: navy blue with a red UP on the front. That was designed by a Penn student on one of the gaming teams.

While there were no Jamaican flags or fans shouting “Woooo," there was a definite “relay” element to the game. Teams had four competitors, each covering a quarter of each course.

There were four courses total: hurdles on a straight path; a snow-lined, curving river; brick piles surrounded by lava; and a forest course of climbs and jumps.

“I don’t think we’ll be importing lava into Franklin Field, as much innovation as we can do,” one of the broadcasters joked.

The forest course had Marine Corps logos because the Marines sponsored the virtual event as they do the real-life one. Scott Ward, the chief operations officer of Penn’s athletic department, didn’t specify the value of the deal, but he did say Penn lost millions of dollars in revenue by canceling this year’s carnival.

“It's just another example of us not wallowing in our own pity and saying we're not going to do anything,” he said. “We were able to come up with this event, and the Marines were gracious enough to still want to be a part of it.”

There were six divisions of competitors: coaches; Marines and fans; college men; college mixed gender; high school boys, and high school mixed gender.

There were not specific girls’ or women’s divisions, Ward said, because there weren’t enough entrants. The esports world is notorious for a lack of gender diversity, but Ward said Penn’s event beat the industry average for female participation — 30% to the usual 10%.

“We were extremely pleased with the results of that,” he said.

The displayed names were mostly aliases, but there were real humans at the controls. Highlights from the coaches’ division included La Salle’s Tom Peterson, Penn assistant Matt Gosselin, and 2016 Olympic 800-meter bronze medalist Clayton Murphy.

“It was really cool to just have something to kind of bring the track and field community together,” Gosselin said. “I was honestly pretty surprised with how realistic everything was.”

The stream’s broadcasters noted that many of the high school athletes competing were real-life track and cross-country runners. A few schools’ names popped up on the screen along the way: Germantown Friends, Perkiomen Valley, Brick Township of Ocean County, N.J.

Ward said when the entry application opened, responses came from across the Relays faithful. While most of the high schools were local, there were applications from California’s Long Beach Poly and Jamaica’s Calabar — two famous names at the track.

The college field included many regular Penn students, who aren’t known for going to games on campus. Ward highlighted UPennCraft, a student group that’s been designing Penn buildings in Minecraft form.

“It was extremely rewarding to know that here’s something that we can connect students on campus with, that may have never been to a real event at Franklin Field,” Ward said.

Guests on the broadcast included Carl Lewis, who went from Willingboro High to Franklin Field to Olympic stardom.

Now a coach at the University of Houston, Lewis said he missed “the chance for Philadelphia to show what a beautiful city it is, and for other people in the world to witness that.”

But he enjoyed the virtual competition, he said, as a way “to bring people together, give them something to look forward to at a time when we don't know what tomorrow is going to be like.”

Longtime Relays director Dave Johnson said “nobody needs to feel badly — of course we made the right decision,” to call off the meet.

But there was still some sadness in his voice.

“The people I feel bad for are the high school seniors who worked their butts off for three or four years to make their Relays team this year for the first time … and it would have been the one time to run in front of 30 or 40,000 people,” he said.

Relays organizers were planning to add an esports element to the annual carnival before this year’s human edition was canceled. Ward said there probably would have been gaming stations in the Palestra this weekend if things had gone according to plan.

“We still wanted to do something,” Ward said. “We’ve been able to put on an event that’s kind of keeping the Penn Relays in people’s minds during this time of year when it’s especially hard to have content, or those social connections.”