Fifty years ago in Penn’s sunlit basketball season, a gifted player was heading for the shadows

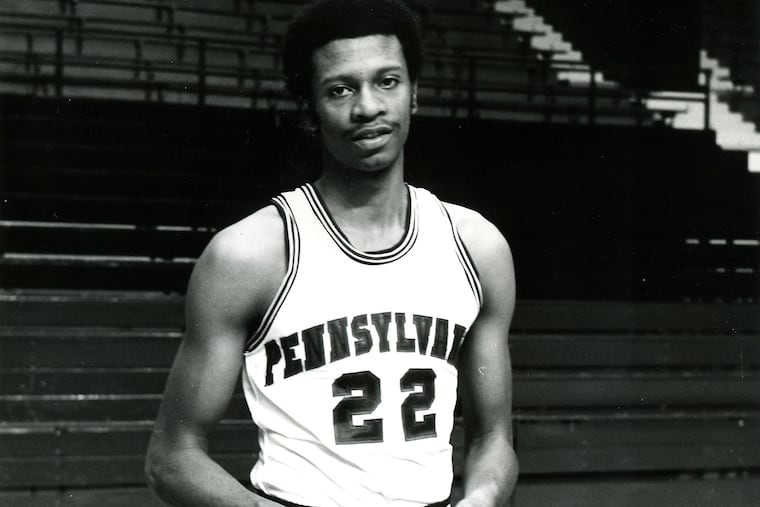

Phil Hankinson, a star player on that memorable Penn NCAA tournament team, saw his life go adrift after an injury ended his brief NBA career.

As one after another the aging faces materialized on computer screens during a recent Zoom call that served as their 50th reunion, the members of Penn’s 1970-71 basketball team formed an expanding quilt of memory.

Scattered across the U.S. now, these old men leaned eagerly into their virtual huddle as if, amid the din of a packed Palestra, they were young again and together, straining to hear coach Dick Harter’s orders.

Bobby Morse, Dave Wohl, Corky Calhoun and the others chattered about Harter, the ex-Marine who drilled them like Leathernecks; about victories over Ohio State, Syracuse, South Carolina; about the giddy elation of their first 28 games and the crushing gloom of that infamous NCAA loss to Villanova in their 29th.

» READ MORE: Penn coach Steve Donahue on a season that wasn’t, and how he’ll change his tactics | Mike Jensen

Gradually, the wistful reminiscing turned to the one missing face in this pixeled patchwork, a 6-foot-8 forward who may have been the most gifted among them and surely was the most bewildering.

Phil Hankinson had missed the 25th reunion too. If his teammates didn’t immediately understand why, they’d find out a few months later. On Nov. 19, 1996, alongside a Kentucky highway, Hankinson, 45, was discovered dead in his car. He had died by suicide.

Police theorized he’d been en route to Las Vegas, where he was due to resume the security job he’d abandoned months earlier. Inside the 1991 Buick where his body was found were three new shirts, copies of his resume, a Bible and a 1976-77 NBA Guide that listed the modest statistics from Hankinson’s brief NBA existence.

Conversations with his brother and teammates, along with contemporary accounts from police and from mental health experts in a 1997 Boston Globe article reveal how Hankinson’s troubles accelerated following the 1974 knee injury that ended his basketball career. With few close friends, he increasingly isolated himself. Depressed, alone, adrift, gripped by self-doubt and unable or unwilling to seek help, he began hearing voices and was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

“What that ’71 team did was a great accomplishment. But sometimes we glorify the wrong things. Sometimes that spotlight needs to shine on something tangible for the rest of society.”

His tragic story is a reminder that in remembering sunlit sports seasons like the one Penn experienced a half-century ago, the shadows often go unexplored. Maybe the best way to mark a milestone anniversary like this might not be with another recitation of those Quakers’ glories but instead with a look back at Hankinson’s life and especially his death. And by doing so, by acknowledging the mental illness, perhaps others will be helped and the roll call of highlights from Penn’s wonder year will expand exponentially.

“What that ’71 team did was a great accomplishment,” said Ken Hankinson, Phil’s younger brother. “But sometimes we glorify the wrong things. Sometimes that spotlight needs to shine on something tangible for the rest of society. A lot of athletes suffer from mental illness. Some take their lives. It’s a hard thing to understand, a hard thing to treat. If someone is hell-bent on doing it, how do you know? And if you do know, what do you do? What’s the answer?”

What almost no one knew was that the ex-Penn star had spent years drifting from job to job, place to place, searching for respite from the voices in his head.

Except for roommate Craig Littlepage, Hankinson had lost contact with his Penn teammates. He never married, had few friends, lived alone. As his illness worsened, he grew more reclusive, more reluctant to seek help.

One who tried to assist in 1992 was Mel Davis of the NBA Players Association.

“He had no self-esteem or confidence,” said Davis. “Life after basketball just scared him.”

‘As good as any of them’

That 1970-71 season, when 15 future Big 5 Hall of Famers and three future NBA coaches were active, was the Big 5′s mountaintop season. And Penn was king of that hill. In Hankinson’s three varsity seasons, under Harter and then Chuck Daly, the Quakers won 74 of 85 games, went 39-3 in the Ivy, 11-1 in the Big 5.

Inspired by Bill Bradley’s Princeton, the school had upped its basketball ambitions. Harter, hired in 1966, brought in charismatic Digger Phelps, the future Notre Dame coach and ESPN basketball commentator, to be his chief recruiter.

Phelps didn’t have to look hard for Hankinson. As a senior at Long Island’s Great Neck North High, the forward averaged 29 points and 17 rebounds.

“Phil was a really talented kid,” recalled Phelps, now retired in South Bend, Ind. “He could do a lot of things. There were a lot of good players on Long Island then, including Julius Erving, and Phil was as good as any of them.”

Hankinson was born in Augusta, Ga. – close to his father’s South Carolina hometown of Aiken. When his parents divorced in 1963, he moved to Long Island with his mother and brother.

“He was an introvert,” recalled Ken, a financial adviser with New York Life Insurance in Manhattan. “He could connect with people, but he was very comfortable hanging out by himself, reading and doing schoolwork.”

» READ MORE: The greatest play in St. Joe’s history helped inspire the term ‘March Madness’ 40 years ago | Mike Jensen

One place that drew him out was the neighborhood playground, where the tall and athletic youngster got attached to basketball. He followed the game, studied its history, honed his skills.

“He went all-in,” said Ken. “Sometimes it would be so dark at the playground that I couldn’t see, but he wouldn’t leave. He said if you could make them in the dark, you could make them when there was light. He had that kind of work-ethic.”

Hankinson grew to 6-8 as a senior and did well on his college boards. Schools from around the nation – including all the Ivies – wanted him.

“It came down to Maryland and Penn and I think he chose Penn because of the academics,” said his brother.

If he never regretted that decision, he questioned it often. Harter demanded a disciplined style while Hankinson’s game might have been better suited to a looser scheme.

“At times he thought he would have fit in better at a place like Maryland or Louisville where the game was opened up,” said Ken. “Harter was hard-nosed and had a theory about how to play. But my brother accepted the environment, was coachable, wasn’t selfish.”

Whatever his misgivings, Hankinson managed one of the best careers in Quaker history. His 518 points were a freshman team record. He was twice an all-Big 5 and all-Ivy performer and in 1980 was inducted into the Big 5 Hall.

“I could not have had a better roommate, teammate or friend. He loved hoops as much as anyone I’ve ever been around.”

“His short-range jumper was really hard to block because he released the ball with arms almost fully extended, used a high arc and a little fadeaway when needed. He had a soft touch,” said Morse, that team’s top scorer. “Now, 50 years later, when I shoot around, I still remember Phil and what he taught me.”

As a sophomore on that ‘70-’71 team, Hankinson became Harter’s first sub, averaging 9 points and 6 rebounds a game.

With Morse hitting long-range jumpers, Calhoun blanketing the opponents’ best players and Wohl and Steve Bilsky controlling the pace, Penn defeated Ohio State on the road early, then topped La Salle, Syracuse, Utah, Temple and Princeton in succession. The Quakers climbed to No. 4 in the AP Poll on Jan. 11 and stayed there until, despite the infamous 90-47 loss to Villanova in the East Region final, it rose to No. 3 in 1971′s final ranking.

Hankinson, Littlepage, John Koller, Allen Cotler and Ron Billingslea provided so much energy off the bench that teammates nicknamed them the EarthQuakers.

“They gave us a tougher time in practice than most of the teams we played that year,” said Wohl, retired in Southern California after a long career as an NBA player and coach.

Away from the court, those Quakers were, in Littlepage’s words, “an eclectic group of guys” who rarely socialized together. While Hankinson’s circle of intimates was small, teammates appreciated his upbeat attitude. In public at least, there were no signs of the anguish to come.

“I could not have had a better roommate, teammate or friend,” said Littlepage, the Cheltenham High product who served 17 years as Virginia’s athletic director. “He loved hoops as much as anyone I’ve ever been around.”

After Hankinson’s death, Harter, who died in 2012, called him the most likeable player he’d ever coached.

“You’d see him and start smiling,” Harter said. “He was maybe too nice a guy for the world.”

He averaged 16 points and 8 rebounds as a junior for the 25-2 Quakers, who for a second straight year lost in the Elite Eight. His numbers improved to 17 and 9 senior year, though Penn slipped to 21-5 and a second-round NCAA elimination.

Toward the end of that senior year, eagerly awaiting the 1973 NBA Draft, Hankinson apparently began to neglect his studies. He told his family he wouldn’t be getting a diploma.

Career cut short

Meanwhile in Boston, Red Auerbach saw Hankinson as a potential replacement for the aging John Havlicek. Convinced he could get him in Round 2, the Celts’ GM took Indiana guard Steve Downing with his first selection, then got Hankinson with the draft’s 35th pick. The ABA’s New York Nets, who played near his Long Island home, also picked him, in the fourth round.

“He never really considered the Nets,” said his brother. “Boston had tradition and getting picked by Red Auerbach, who had a great eye for talent, was something he was proud of. But at that time rookies didn’t play. They carried the bags.”

In Hankinson’s first season, the Celtics won their 12th NBA championship, but he appeared in only 28 games, averaging 3.9 points.

“We would laugh about Phil having such a great seat to watch John Havlicek and me having a great seat to watch Pete Maravich,” said Tom Ingelsby, the Villanova star who then was an Atlanta Hawks rookie.

That summer, teammate Paul Westphal, who felt Hankinson was too self-critical, invited him to play in a Los Angeles summer league. During one game, Hankinson came down with a rebound and fell to the ground. He’d torn his ACL.

Doctors couldn’t help much and when he returned to the Celtics late in 1974-75, his quickness, according to coach Tommy Heinsohn, had been diminished by 70 percent. He played in just three games and was released. Not yet 24, his basketball career was over.

“Once he left the Celtics he never recovered that drive,” said Ken. “It wasn’t an easy transition. You’re a high school star and everybody on the Island knows you. Then you go to Penn and you’re a star there and everybody on campus knows you. And then you go the NBA and your first year you win a ring. Then you hurt your knee and shortly after that the ABA folds so there aren’t many spots for you. What do you do?”

Many would trace the roots of his suicide back to that injury. But while such a traumatic disappointment can exacerbate a mental illness, experts said, it can’t cause one. Hankinson was sick and his isolation hid that reality from all but a few.

“He was fiercely independent,” said Littlepage, “and never wanted anyone to worry about him.”

Through the years, Hankinson took janitorial jobs, pumped gas, sold sporting goods, coached basketball. He moved from New York to South Carolina to Las Vegas. That last year he lived in a $510-a-month apartment near the Las Vegas strip and a rented trailer in Aiken.

In 1982, Littlepage convinced his old friend to come back to Penn. Hankinson took several courses and worked in the university’s parking system. According to one of the resumes, he hoped to earn his sociology degree in 1984, but eventually left without it.

» READ MORE: Philly referees have dominated NBA officiating for decades. Here’s why.

“He seemed generally more subdued when he returned,” recalled Littlepage, “his demeanor had changed.”

In the early ’90s, he contacted the Players Association. He was helped financially and Davis, whose own NBA career ended with a knee injury, asked Hankinson to speak to the league’s 1992 rookies when they gathered in Orlando. He hoped the ex-Penn star could inspire them to seek help if and when they needed it.

Davis said it took Hankinson six months to prepare, but his talk, filled with “don’t-do-as-I-did” cautions, had an impact.

By all accounts, the demons were raging by 1996. Hankinson quit his casino job in August and at some point headed to South Carolina.

On Sept. 10, near Amarillo, Texas, he blacked out and his car landed in a ditch. His erratic behavior concerned police who took him to Northwest Texas Hospital. Doctors there prescribed the anti-psychotic drug Haldol.

Reaching Aiken, Hankinson rented a cheap trailer. But when the episodes continued, he was sent to University Hospital in Augusta. His brother said he was given Risperdal and started therapy.

His condition improved, until he stopped taking the medication.

“I said ‘You can’t stop,’ ” Ken recalled. “He kept saying he felt all right and I told him that was because of the medication and therapy. But he was fighting it the whole way.”

Not long before he left South Carolina that final time, Hankinson visited several relatives. He was, his brother now believes, saying goodbye. On Nov. 12, he telephoned his brother.

“He said, ‘Listen, no matter what happens, I love you,’ ” recalled Ken. “I told him I loved him too. I thought it was odd because he was never outwardly emotional, but it was my birthday. The part that really stuck with me was him saying, ‘No matter what happens.’ That was the last time we spoke.”

Shortly after Hankinson departed on Nov. 18 he stopped at an Aiken store to purchase the shirts, a bag of potato chips and a .22 caliber handgun.

The police who found his body had questions. If he was heading west, why was his car on an eastbound shoulder? If he was Las Vegas-bound, why was he so far north of the most direct route?

Eventually Kentucky police reached Hankinson’s father. Distraught, Rube Hankinson, who will soon turn 90, asked his sister to pass the news to Ken.

“My aunt called me,” Ken said, “and that’s when the nightmare started.”

Hankinson’s funeral took place at Aiken’s Second Baptist Church. Knowing the pain basketball had caused him, the family notified just a few former teammates. Only Littlepage attended from the ’70-’71 Quakers.

“We didn’t want a lot of fanfare,” said Ken. “Basketball was his job, a career. That was it.”

“I look back now and wonder if maybe one of us could have gotten Phil a job in coaching. I know I could have done more.”

Most Penn players didn’t find out about Hankinson’s death until much later, when it was too late to intervene.

“I look back now and wonder if maybe one of us could have gotten Phil a job in coaching,” said Wohl. “I know I could have done more.”

For Ken Hankinson, who participated in Penn’s recent Zoom reunion, it remains difficult to talk about the suicide. He did so now because “it’s important that mental illness isn’t kept in the closet.”

“The toughest part is that I didn’t know the depths of pain my brother was feeling,” he said. “Nobody wants to see a family member suffer alone. By talking I’m honoring my brother. Maybe it will help someone. People who don’t have celebrities in their families are dealing with these issues and don’t know what to do.”

Three years before Hankinson’s death, Celtics star Reggie Lewis died suddenly of a heart ailment, A few days later Boston GM Jan Volk got an unexpected letter.

“I know receiving a letter from me has sent you into total shock,” Phil Hankinson wrote. “I still have a deep emotional attachment to the team. I feel fortunate that at least once in my life I was part of something great.”

Curiously, the one physical reminder of that cherished moment, his championship ring, stayed with Hankinson through all his torment and money problems, After his death, it was returned to the family with the rest of his belongings. The boxes remain unopened, the ring undisturbed.

“We’ve never looked for it,” said Ken. “Nobody went and got it. We just left it there.”