Phil Mancuso and Angelo Scuderi upheld Philadelphia’s Italian American food traditions

Phil Mancuso, a ricotta master, and Angelo Scuderi, a nightside baker, died on the same day.

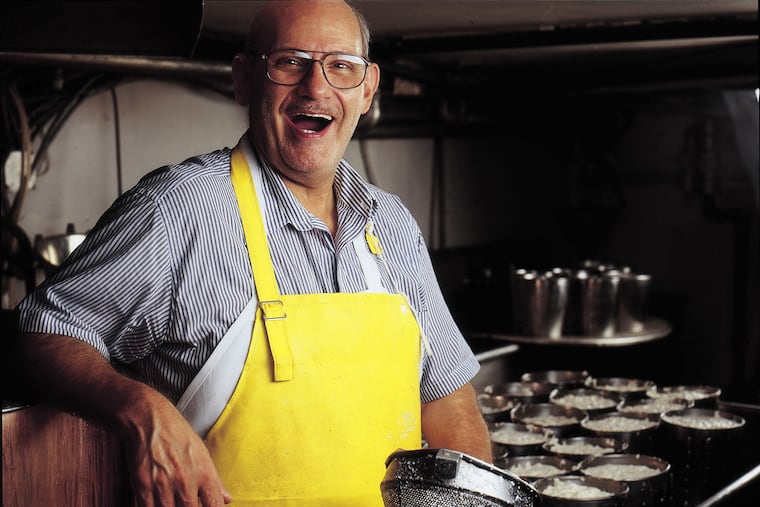

Philip M. Mancuso was an institution in his own right, a master cheese maker, raconteur, and water ice wizard who proudly maintained his family’s 81-year-old Italian grocery on East Passyunk Avenue, where he often handed slices of his legendary fresh ricotta to customers with a song.

Angelo R. Scuderi led the behind-the-scenes career of a night baker, mixing and portioning dough at several renowned South Philadelphia bakeries while most of the city slept. But after decades of producing rolls for the bakery that supplied Pat’s Steaks and Geno’s, followed by 22 years at Sarcone’s Bakery, he had an essential hand in producing millions of great hoagies and cheesesteaks.

“Once in a while we’d be driving around and he’d say, ‘Hey, you see that restaurant there? I made their bread,’ ” said Scuderi’s nephew Charles-R. “Kiefer” Adams. “He didn’t ever complain about the anonymity of his work, but he was very proud of it.”

Both men died on the same day, on Feb. 11 — Mancuso at 84 of complications from kidney disease; Scuderi at 63 from diabetes. And with their passing, a generation that upheld South Philadelphia’s long-standing Italian American foodways continued to disappear.

“Old-school guys, man, the last of a dying breed,” says Danny DiGiampietro, the owner of nearby Angelo’s Pizzeria, who snapped a haunting picture of Scuderi last spring snoozing out front of Sarcone’s at 5 a.m. “A lot of people say that sight of him sleeping was what they always saw driving up Ninth Street early in the morning. He was truly a hard worker, but he’d take catnaps between batches.”

“The more I talk about this the more I realize this is a blow to the neighborhood,” said Francis Cretarola, the co-owner of Le Virtù, reflecting on the death of his cross-street neighbor, Phil Mancuso. “I hope he understood what he meant to people in so many ways. ... The Italian American presence in this neighborhood is still strong, but places like Phil’s [grocery] were where it could coalesce and express itself.

Entering Mancuso’s tightly packed market was like stepping into a time capsule of mid-20th-century aromas and sounds. Little had changed since Phil’s father, Lucio Mancuso, opened the store in 1940, from its heady smell of cured meats and open tubs of olives, to the crowded shelves of Calabrian pastas, olive oils, tinned sardines, and stacks of imported cheeses behind the counter where still-warm braids of freshly pulled mozzarella were dipped in a salt water bath to order. Conversations could be heard in Italian against a soundtrack of classic opera.

Mancuso’s largely served a local audience of first- and second-generation Italian immigrant families who’d settled in the rowhouse neighborhoods nearby and came to “the Avenue” to shop, not just for cheese, but for cooling summer scoops of water ice tinted dark with chocolate or citrusy bright with fresh sparks of lemon pith. And there were many other grocers just like it. By the early 2000s, however, as South Philadelphia’s demographics shifted with Mexican and Southeast Asian immigrants, and East Passyunk experienced dramatic gentrification, Phil Mancuso clung to his traditions as tightly as ever.

“My dad wanted to preserve things the way they were to continue his father’s legacy,” said Robert Mancuso, 50, the youngest of three sons Phil had with his wife of 55 years, Adelaide “Edda” Mancuso.

“He had jars of pickled mushrooms and artichokes that were 45 years old and he refused to throw them away,” says Edda Mancuso. “ ‘For memories!’ he’d say. He was attached to this stuff. But I got to throw it away now or somebody’s going to buy them by accident!”

That passion sparked a dormant yearning in customers like Cretarola to reconnect with his own Italian roots, leading him to the study of Abruzzo and the eventual opening of Le Virtù in 2007: “Mr. Mancuso, in his own way, was pivotal in why we exist,” he says.

Mancuso’s love of singing opera went hand in hand with his passion for making cheese, especially the moist round cakes of fresh ricotta and basket cheese (for Easter) that he’d make weekly in the steamy basement workshop he called “the crypt,” where he once showed Inquirer food columnist Rick Nichols the craft he’d learned from his father, grandfather and uncles, who made ricotta on Ninth Street in the 1920s.

“ ‘Am I an opera lover?’ Phil Mancuso asks, not caring to hear the answer,” Nichols wrote. “ ‘Come back and I’ll take the ricotta out and we’ll go to Franco & Luigi’s and I’ll sing you a song. What’s better than that!’ ”

It was a one-two charm offensive Mancuso had employed often, not the least of which was with his wife, who first stopped into the store in 1964 as an Italian tourist on vacation from Reggio Calabria looking for mozzarella. Edda DeFazio got her cheese, but also got a dinner invite from Phil, who took her to Victor Café, which is known for its singing waiters and where, yes, he sang her an aria and pledged: “I’m going to come to Italy and marry you.”

He followed through on that promise, bringing her back to Philadelphia for more than half a century highlighted by raising a family (now with six grandkids), countless open mics and opera recitals at their home, and, of course, maintaining the family store. At least until now.

Longtime manager Larry Ferrari still faithfully makes the cheese — “he taught me everything and I’m keeping that legacy going, because that’s what he’d want me to do.” But none of the Mancuso heirs seem interested in taking the business on: “There’s no way I can keep this open, I’m not young anymore,” says Edda Mancuso, 83.

That’s dispiriting for fans like Cretarola: “As that gets lost, a lot of the [Italian American] culture is in jeopardy because there’s no one to teach it, who remembers it all. [Phil] could trace the entire arc.”

The legacy of South Philadelphia’s Italian baking tradition seems a bit more secure as long as cheesesteak and hoagie lovers value the crusty, seeded rolls like those Angelo Scuderi oversaw the production of at Sarcone’s, the 103-year-old bakery, now in its fifth generation of family ownership.

Scuderi was instrumental in keeping that institution going in his role as head dough mixer, arriving each night at 11:30 p.m. and not leaving until 8 a.m.

“He was my quarterback, because the dough mixer is the top spot in a bakery,” says fourth-generation owner Louis “Big Lou” Sarcone Jr. “He has to gauge the temperature outside, whether it’s rainy or dry, and it was up to him to set the dough for the day right. I trusted him with all that, because he was an old-school born-and-raised baker. He wasn’t just a laborer.”

Many of today’s bread manufacturers are fully automated. But Sarcone Jr. knew the value of Scuderi’s intuitive skill set for a bakery with century-old hearths like his own, where bread is still made by hand daily in oil-fired ovens without chemicals or preservatives. He hired Scuderi on the spot when his previous employer, Vilotti-Marinelli, closed over two decades ago. Over that time he estimates Scuderi oversaw production of 16.5 million loaves of Sarcone’s bread.

“He made a lot of people in this area very happy for a long time and never got any recognition,” said his friend Danny DiGiampietro.

Scuderi, who spent most of his career on the night shift, never married or had children but helped his sister raise her two sons in South Philadelphia.

“He just became a dad to my brother, Joey, and me and raised us as his own,” says Adams, who notes that Scuderi, whom they called “Uncle Ricky,” was an avid rock guitarist who once played his Stratocaster with a band in gigs at J.C. Dobbs on South Street. He built clay models. He was a Star Wars fan, and a regular attendee at Comic-Con.

But mostly, he was obsessed with baking, even at home, when he’d make the family pizza from fresh dough in his off hours.

“My wife and I were just talking about how he and the cheese guy [Phil Mancuso] happened to die on the same day,” says Adams. “I guess God is making stromboli for dinner.”