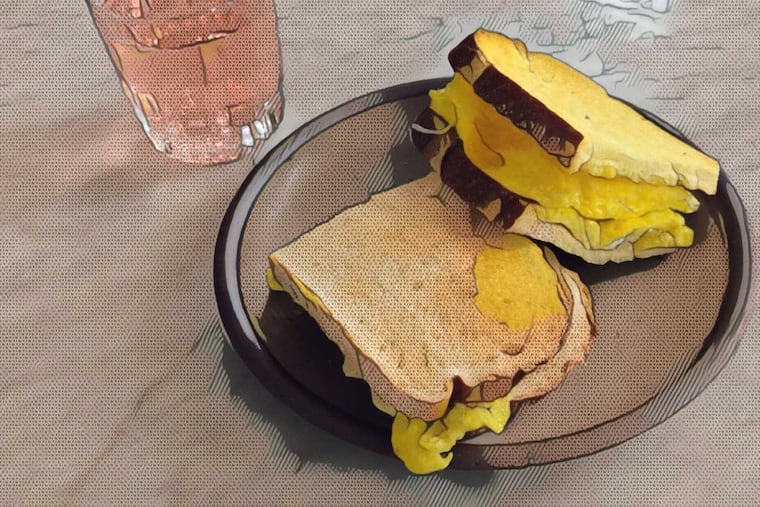

Self-love is an egg sandwich with hot sauce

Navigating depression and loneliness while hiding a secret, one writer explores how food helped him find himself again.

When I moved out on my own to attend college, I lived with three sloppy boys in an off-campus apartment, where the carpet was always crunchy, lightbulbs went out but were never replaced, and it smelled faintly of mildew.

Because it was an environmental disaster, the apartment never felt like home. Instead of hanging out with my roommates, who eagerly lived as bachelors on the loose in the world for the first time, I found myself taking on two restaurant jobs just to get out of the house.

I didn’t even take my meals at home, subsisting on fast food or free shift meals instead. The main reason: Cooking in that kitchen was a disgusting prospect. The stove was caked with splatters of weeks- and months-old sauces and god knows what else. Dishes “soaked” in fetid water for days at a time, no one owning up to their messes. The fridge, empty save for cans of Miller and Coors, always emitted a mysterious funk.

In this apartment, I resigned myself to a life of loneliness. I was always surrounded by people — my roommates, their friends and dates — but I’d stick to my room. When I did cook, my meal would inevitably be a single fried or hard-scrambled egg that I’d shimmy onto a piece of toasted white bread, topped with hot sauce or ketchup. Afterward, I’d clean out the frying pan I bought for this specific purpose and stash in my room, lest it found its way into the swamp of a sink, never to be seen again.

That hermit’s meal of an egg sandwich was my only comfort most days, but just barely. I’d eat it in the dark living room while watching basic cable, hoping my friends would call me to hang out but too scared of rejection to do the asking myself.

I thought I deserved this existence.

Months prior, right before they moved to another state, my parents discovered that I was gay. “You’ll die alone,” my wailing mother cried, conjuring a dark, inevitable prophecy that I manifested daily. I quickly put that secret back into my personal Pandora’s box, terrified that I would cause more harm to myself if other people knew. I felt that if my secret got out, I’d lose my friends, just like I lost my family.

While my friends and roommates celebrated the carefree invincibility of early college freedom in sun-kissed Orange County, I lived a solitary half-life. It was made of piled-up Wendy’s bags, rapidly declining grades, and late-night crying jags as I drove up and down the Pacific Coast highway, listening to Dashboard Confessional and Something Corporate. I was certain my life held nothing more than a lonely routine of sitting and waiting, that egg sandwich a depressing constant.

Eventually, I broke.

One night, I found myself on an unknown street in a gated community after an ill-advised hookup, snapping out of an out-of-body experience. I was terrified — I didn’t know how I got here. I realized that many of my firsts — first date, first kiss, first fling — felt like they happened to someone who had taken over my body, my brain on cruise control. Under that streetlamp next to my car, I felt my life yawning before me, an unnavigable void. I was 18 years old.

I know now, after years of therapy, that this inky, seemingly infinite darkness was depression, but the chilly terror I felt ran straight to my marrow. I didn’t know what I was doing, but I knew I didn’t want to find myself on that oppressive midnight street ever again. In the weeks following, I somehow found a tiny sparkle of light in that void, which was enough to start finding a path back to myself.

I started with what I could control: I cleaned the dishes and scrubbed that kitchen until my hands were raw.

I also started cooking in earnest. First, childhood favorites like meat loaf, pancit, and adobo, and then, when I had convinced my roommates they’d have better chances dating if the apartment was clean, I began hosting dinner parties. I cooked big pots of bolognese and too many meatballs; misshapen greasy discs I tried to pass off as pepperoni pizza; and so much soup. As I found myself, I also found that cooking grounded me in the present. My mind focused on the tasks, while my body benefited from eating more wholesome, nourishing foods. I was building up a strength I didn’t know I had.

Most crucially, I called my friends I had been avoiding. I invited them to my hosted dinners. I told them my crushing secret. I made myself vulnerable, and so did they, and together, we found ourselves. It’d be years before I learned the term “chosen family,” but that’s what we were.

It’s been almost 20 years since I disproved my mother’s parental catastrophizing, and though I still feel alone sometimes, I know it will pass. When the dark tries to creep back in, I fall into a new version of that old routine: I’ll pour myself a glass of wine and make an egg sandwich doused in hot sauce. I remember that past self while honoring my present. And while I love cooking for and feeding my husband, our friends and family, I always remember to feed myself first, to savor every bite and moment I am in my own body, as myself.