Dewey’s sit-ins sparked a generation of LGBTQIA social change

Historians consider the Dewey’s restaurant sit-ins for LGBTQ rights the first of its kind.

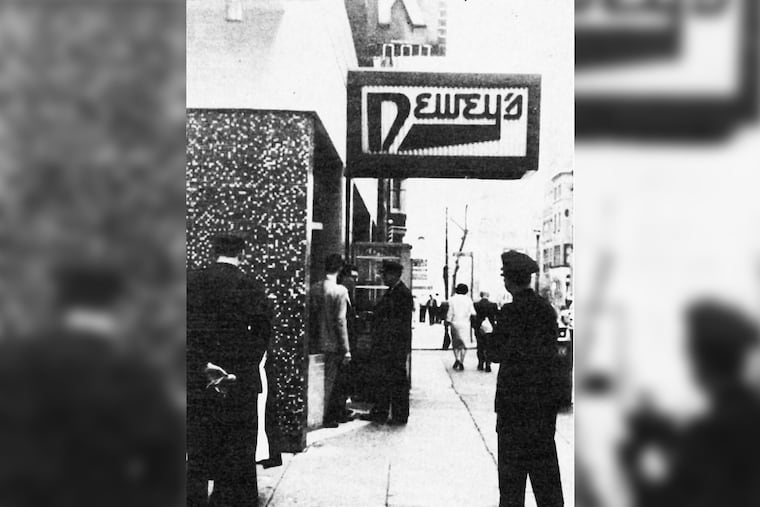

On April 25, 1965, the first of two sit-ins occurred at Dewey’s restaurant at 219 S. 17th St. in Philadelphia. That day, inspired by the sit-ins in the segregated South by civil rights activists, LGBTQ activists sat down to protest the establishment’s refusal to serve what Clark Polak, one of the protesters and president of the Janus Society, a Philadelphia-based homophile organization, described as “a large number of homosexuals and persons wearing nonconformist clothing.”

Dewey’s was a small local diner chain that began in the mid-1950s and was open all night. Naturally, it would attract a colorful crowd in the wee hours of the morning — and the location near Rittenhouse Square became a hang out for the local LGBTQ community by the mid-1960s because of its proximity to the local bars.

“At two or three in the morning, you’d find streetwalkers, you’d find drag queens, you would find everybody,” remembers Joan Fleishmann, a member of both the Philadelphia Mattachine and Janus societies. Fleishmann even met Liberace at Dewey’s one night. The crowd was racially diverse, known as a good spot to warm up with a cup of coffee, or maybe meet people.

But then in spring 1965, Dewey’s began to deny service to people based on their perceived sexuality or gender identity. In an oral history from 1993, resident Bill Brinsfield recalls a “vulgar” sign stating their new policy.

According to various records, on April 25, three gender-variant teenagers, whose names are lost to history, refused to leave when they and reportedly up to 150 people — Black, white, trans, gay — were refused service. Polak rushed to the scene to offer assistance and the four were arrested and charged with disorderly conduct.

In reaction, the community energized. Over the following week, activists with the Janus Society distributed 1,500 leaflets and met with local authorities and restaurant representatives, while others demonstrated against Dewey’s homophobic policy.

A second sit-in would be organized for a week later, but this time the local police would leave the activists alone. Soon after, Dewey’s would reform its policies. Victory was declared.

Historians consider the Dewey’s sit-ins for LGBTQ rights the first of its kind, applying the tactics of the civil rights movement to their cause. Activists made headlines in 1960 when North Carolina students refused to leave a “whites only” Woolworth counter, which sparked hundreds of Black and white students to join them and jump-started similar sit-ins around the South. Their brave work would help force desegregation and federal policy change and inspire the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — although compliance enforcement would be uneven through the 1960s.

Restaurants were often the choice for sit-ins, which accompanied resistance against integration, be it race, sexuality, or gender expression. Eating was considered such an “intimate” act, as race and food studies scholar Angela Jill Cooley writes in her book, To Live and Dine in Dixie, white supremacists were afraid meals would lead to “even more intimate interactions.”

“There’s something deeply personal about the places we eat — they are also markers of identity and shared community,” says Philadelphia native Garret Broad, an associate professor at Fordham University and author of More Than Just Food: Food Justice and Community Change. He says restaurants become flashpoints of both discrimination and activism. “It’s a bold statement to say ‘no, you should not be revolted by me — we are human,’” he says.

» READ MORE: Take our walking tour of Philly’s LGBTQ history

What makes food a particularly potent place for discrimination is also what allows political and social change to foment there. The act of coming together over a meal seeds equity and peace, and sharing foods can bridge cultural differences. Being able to share a place to eat “is a comment on shared humanity,” says Broad.

Gabrielle Lenart, a Philadelphia-area native, activist, and founding member of the community mutual aid project Queer Food Foundation, also notes the long history of “common places like restaurants not being seen as safe places” for members of the queer community, who were often forced to gather in private. Lenart says that “the easiest way [to marginalize] any historically excluded group or minority [is through food].” The Dewey restaurant sit-ins were a moment when this marginalized group sought to reclaim their identity in a public space.

The legacy of the activists who took part in these sit-ins can still be seen today in the food industry — and beyond. Lenart says there has been a resurgence in LGBTQIA+ communities — “chefs, media experts, farmworkers, sommeliers — anybody who works in food puts their identity in what they’re making.”

It has only been in the last 25 years, Lenart notes, that queer people were acknowledged in popular media. Lenart, who has been researching representation of queer people in food media, emphasizes that there is still erasure of the stories of Black and trans food activists, among other marginalized identities.

A remembrance of the participants in the Dewey restaurants sit-ins helps to illustrate the contributions of these diverse queer activists..