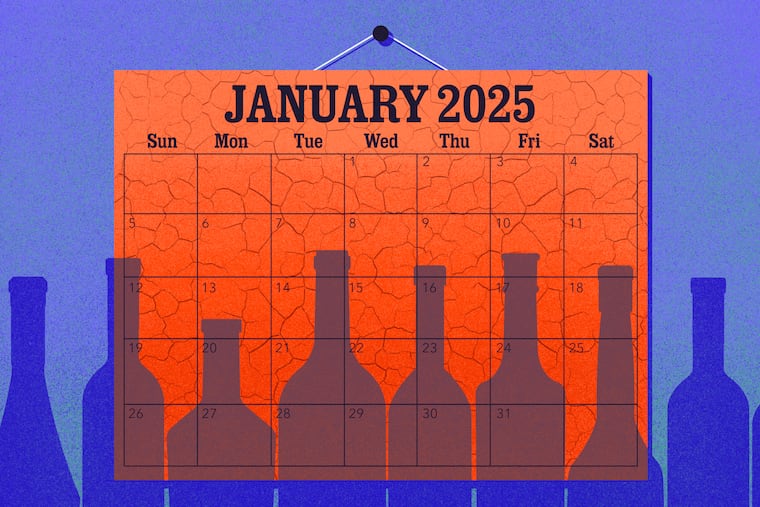

Philadelphians are embracing Dry January, but have trouble sticking to it

Statewide alcohol sales saw a 21% drop last January in Philadelphia.

When the pandemic drove people into indoor isolation, Anna Simon did what many adults did — she started drinking more.

“Doing a daily happy hour became the transition from the workday to the evening,” Simon, a Passyunk Square resident, said.

As the months went on, she noticed she didn’t like how the regular cadence of alcohol made her feel. But even though most days she was only having a drink or two, she noticed it zapped her energy and productivity. She said she realized drinking had become a thoughtless habit.

Simon decided to try Dry January, a challenge to abstain from drinking for the month, in 2021. It’s now something she does annually, and she credits using a mindful-drinking app with moderating her consumption year-round. Still, she’s looking forward to breaking her streak on Feb. 1 with a martini from Friday Saturday Sunday.

Simon likely has company in Philadelphia and across Pennsylvania.

The Inquirer analyzed daily sales at each of the 590 state-owned Fine Wine and Good Spirits stores from July 2023 to June 2024, looking at a granular level at how much wine and liquor Pennsylvanians were buying, and when. Liquor sales reached their lowest point at the beginning of January.

As New Year’s celebrations faded to memory, sales in Philadelphia fell to 21% below their weekly average. Statewide, sales were 31% below the weekly average during the first week of January.

But Simon noted she’s never been able to make it all the way to Jan. 31. Here, too, she’s not alone.

At liquor stores across the state, alcohol sales crept back toward normal as January wore on, The Inquirer’s analysis found. By the first week of February, sales were down only 3% off their average. And while these data do not include beer sales or alcohol sold outside the State Store system, like sales at bars, Philadelphians have noticed both ends of the Dry January phenomenon.

“On January 1st, the world is your oyster and you think you can accomplish anything,” said Ben Fileccia, senior vice president of the Pennsylvania Restaurant and Lodging Association. “A few days into the new year, all of a sudden, you are back to your old, original ways.”

Not just Shirley Temples anymore

Dry January began as a campaign by a U.K.-based charity in 2013, though its roots go back to a similar campaign in Finland in 1942, and the custom of making a change at the start of the year goes back much further. The sobriety pledge has since gone global — a quarter of U.S. adults 21 and older cut out alcohol last year for Dry January, up from 16% in 2023, according to a survey by the polling organization Civic Science.

For those who may feel that abstention is a step too far, Damp January is a newly popular option, too. It’s a half measure, pledging to be more mindful about drinking and consume less, without being quite as rigid.

“Not only is our business going to be slower in general, but then even the same customers that are still coming in, they are going for nonalcoholic beers or mocktails at a much higher rate,” said Amanda Swanson, a local bartender and former president and current board member of the United States Bartenders’ Guild’s Philadelphia chapter.

In Philadelphia last January, sales at some liquor stores dropped by 25% or more compared with their monthly average. People working at bars and restaurants in the city reported similar trends and have adjusted their businesses accordingly.

“We’ve seen zero-proof options on menus just really blow up right now. There’s a lot of people that still want to go out and enjoy themselves and be with their friends without drinking,” Fileccia said.

LaToi Storr, 43, of Southwest Philadelphia, said that the growth of nonalcoholic options has made it easier to keep to her Dry January pledge in her third year doing it.

“They’re actually making the drinks a little bit more fun and easy to order,” she said, “instead of just giving them a Shirley Temple.”

Storr said she asked family members to join in and they told her she was on her own. “But a lot of friends have been doing it, and that’s really helpful,” she said.

Swanson said bartenders understand, too, that while business slows at the start of the month, it will soon pick back up.

“People lose their fortitude once they’ve broken their Dry January — they don’t tend to have that one drink and stay dry for the rest of January. They usually just go, ‘I only lasted two and a half weeks,’ and then that’s it. They’re back to drinking,” she said.

There could be other reasons behind Philly’s dip and rise in alcohol sales — their peak was in December, suggesting some people could have stocked up on booze before the holidays and kept drinking it. People in Pennsylvania buy less alcohol in the winter in general, the analysis found. But Swanson and Fileccia say they believe Dry January is a major factor driving changes in sales.

Swanson said she knows plenty of people who declare their intention to drink heavily for much of December, with a promise to dry out afterward.

“January 1st, bang, Dry January. ‘Cleaning up, atoning for my sins,’” Swanson said.

A cultural shift?

It is unclear whether the growing popularity of Dry January represents a meaningful shift in drinking habits.

Year round, younger generations are drinking less than before. It might not necessarily be a shift toward outright sobriety, as drinks infused with adaptogens like THC or mushrooms have gotten more popular, but it appears that alcohol doesn’t appeal to young people in all the ways it once did, at least for now.

Earlier this month, the surgeon general called for cancer warning labels for alcohol similar to those on tobacco products. Simon said that announcement factored into her Dry January motivations this year, too.

But the pandemic boosted alcohol use after lockdowns and isolation ended. A recent study from the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine found that nationwide alcohol use increased during the pandemic and stayed elevated at least through 2022. In Philadelphia, State Store sales rose each fiscal year from 2020-21 to 2022-23, but remained below pre-pandemic levels.

Increased drinking could explain why so a Dry January reset is so attractive to people, even if it’s not easy to maintain.

Caroline Clancy, 29, of Point Breeze, said she decided at the last minute to join the Dry January masses this year after having an overly indulgent holiday season. So far, she has stayed alcohol-free, and the colder weather of late has kept her from being tempted to go out. But her resolve could be tested soon.

“A couple years ago, I broke it when the Eagles got into the Super Bowl,” she said.